Working on the ‘Front Line’ of Retail Self-checkout

A Survey of the Experiences of Self-checkout Supervisors

Table of Contents:

- Key Findings

- GETTING STARTED

- Context

- Adoption

- Issues

- Management

- The SCO Supervisor Role

- Study Objectives

- Background

- Data Collection

- Introduction

- The Self-checkout Working Environment

- The Self-checkout Operating Experience

- New Insights on the World of Self-checkout

- The Value of Guardianship

- Equipping Guardians I: The Importance of Training

- Equipping Guardians II: Providing Technological Support

- Designing Zones of Control

- Keeping Guardians Safe

- Better Measuring the SCO Environment

- Learning From Front-end Teams

- About the Author

- About ECR Retail Loss

- 25 TALKING POINTS FOR YOUR BUSINESS

- (Endnotes)

Languages :

This report, published in 2022 provides a summary of the findings from a large survey of retail employees tasked with supervising Fixed Self-checkout (SCO) spaces. Using an online questionnaire, staff on the ‘front line’ of SCO provided valuable insights on their experiences of working in this environment, including the training they received, what they witnessed, and their views on how it may be better controlled and managed. It is the second study from a tri-partite research project focused upon developing a more detailed understanding of how retail SCO operations can be better managed and controlled.

Responses were received from over 6,000 staff working in nine retail companies – two based in the US, two in Australia and five in Europe. All were large retailers and predominately grocers, with a combined annual turnover of €292 billion, with a total of nearly 12,000 stores and together employing approximately 1.4 million staff.

Overall, the research concluded the following:

- The Value of Guardianship – the importance of SCO supervision and how retailers need to move from a ‘minimal possible’ staff operating model to one more focussed upon creating a ‘optimum control’ operating environment.

- Equipping Guardians I: The Importance of Training – the research identified the value of training and why it matters. Staff are keen to see their training include more on loss prevention-related issues, how to deal with problematic SCO technologies, and improving their customer service skills.

- Equipping Guardians II: Providing Technological Support – respondents were almost unanimous in expressing frustration with the quality and reliability of SCO technologies. They want to have more reliable, up-to-date, and better designed systems. In addition, they are keen to have a range of alerting options in place to help them do their work more effectively.

- Designing Zones of Control – SCO spaces need to be fit for purpose, having sufficient space to allow staff and customers to move freely and easily, encompassing clear and unambiguous ingress and exit controls. Above all, the design of SCO areas needs to ensure that it amplifies a sense of risk and enables staff to effectively play both a reactive and proactive role.

- Keeping Guardians Safe – retailers have a commitment to protect their staff and to ensure that they are creating a safe working environment for them. The survey has revealed worrying levels of violence and abuse, and respondents believe that in part, this is caused by frustrations generated by current staffing levels and inadequate/glitchy/poorly designed SCO technologies.

- Better Measuring the SCO Environment – more needs to be done to better measure a range of factors that affect the management and control of SCO spaces, not least the frequency of various types of SCO alerts; average SCO alert wait times; average SCO queue times; number of voided/abandoned/walkaway incidents; and the number of incidents of violence and verbal abuse.

The research has highlighted how important people are in this process, but if they are to be successful, they must be given a manageable workload, receive high quality training, be supported with technologies that help them to focus upon the customers, transactions and events that matter, and operate in a space that is well designed, and above all, enables a zone of control to be maintained.

FOREWORD

Welcome to the fifth report from ECR Retail Loss on the issue of Self-checkout (SCO) systems in retailing – a subject, which I’m sure you will agree, continues to grow in importance. This is the second in a series of three reports focussed upon developing a better understanding of how SCO technologies can be more effectively managed and controlled. While the first study looked at it from the perspective of retail businesses, this second study focuses upon those directly employed to look after SCO at the ‘front end’, and how they reflect upon this issue.

Based upon over 6,000 responses to a questionnaire, this research offers fascinating insights into the realities of managing SCO daily, not least the critical role team members play. It describes how important it is that they are properly trained and supported, that they are given the technological tools to better perform their duties, and that the SCO technology itself is both fit for purpose and well maintained. This research also highlights how to date, we as retailers have been slow to fully understand this space, not least because we have not fully developed a series of metrics to both measure its impact upon the business, and the people who work on SCO.

For those with responsibility for the deployment of SCO, I strongly urge you to read this report and if nothing else, reflect upon the ‘25 talking points for your business’ included at the end – they might just help you to better leverage engagement and support for delivering a successful SCO programme in the future!

As ever, I would like to thank Professor Adrian Beck for carrying out this research – he continues to offer excellent support to the retail industry through his research expertise. I would also like to thank Everseen Ltd for the additional research grant that supported this study. As with all the research undertaken on behalf of ECR Retail Loss, it would not be possible without the active support and involvement of the retail community and on this occasion, their SCO teams. Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts and experiences – by working together we are much more likely to Sell More and Lose Less!

Finally, can I encourage you to not only read and share this study, but also take part in the work of ECR Retail Loss – further details can be found at: www.ecrloss.com.

John Fonteijn

Chair of the ECR Retail Loss Group

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report provides a summary of the findings from a large survey of retail employees tasked with supervising Fixed Self-checkout (SCO) spaces. Using an online questionnaire, staff on the ‘front line’ of SCO have provided valuable insights on their experiences of working in this environment, including the training they received, what they witnessed, and their views on how it may be better controlled and managed. It is the second study from a tri-partite research project focused upon developing a more detailed understanding of how retail SCO operations can be better managed and controlled.

Responses were received from over 6,000 staff working in nine retail companies – two based in the US, two in Australia and five in Europe. All were large retailers and predominately grocers, with a combined annual turnover of €292 billion, with a total of nearly 12,000 stores and together employing approximately 1.4 million staff.

Key Findings

The Self-checkout Working Environment

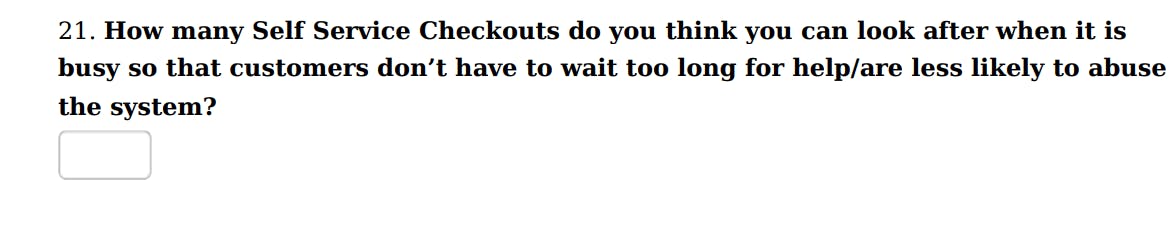

- Most SCO supervisors usually work on their own (59%), with the largest proportion having responsibility for 7 or more SCO machines (38%).

- Nearly two-thirds do not believe they can cope with their allocation of SCO machines or can only cope when they are not busy (63%). As the allocation of SCO machines increases, staff feel less able to cope.

- A significant majority of respondents believe that between 1-6 machines per member of staff is the optimum ratio (84%). While SCO machine ratio is a useful indicator, allocating labour to SCO spaces should also take account of transaction volume and velocity, the alerting context (e.g., age checking requirements), use of control interventions (e.g., security weight checking), and the crime-risk rating for any given store.

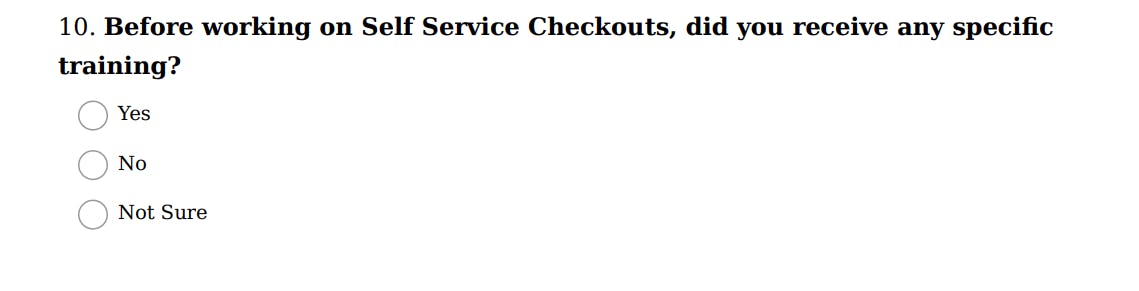

Self-checkout Training

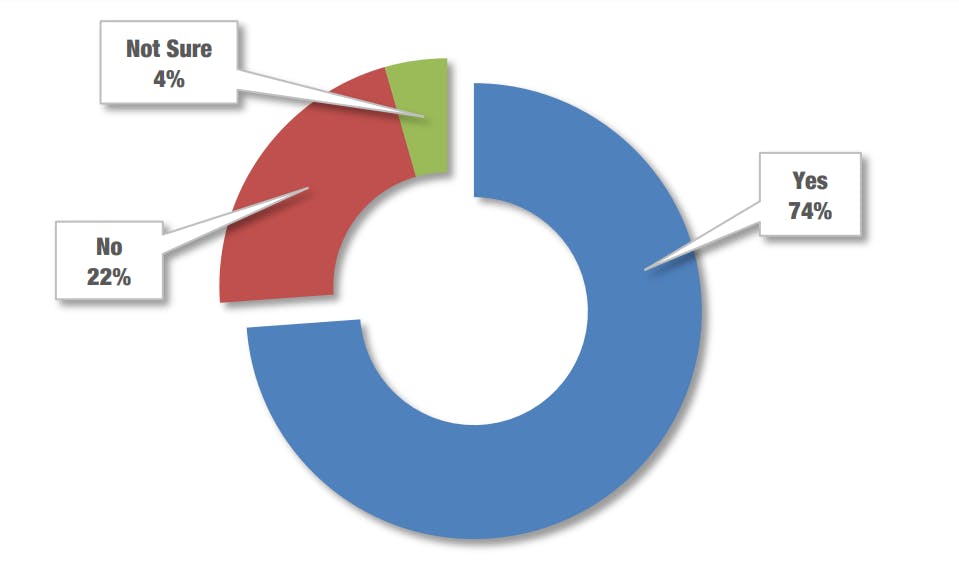

- Most staff had received training prior to working on SCO (74%) although those who worked on SCO only when it was busy were more likely to have not received training.

- Those who had received training were more likely to feel that they could cope with their workload.

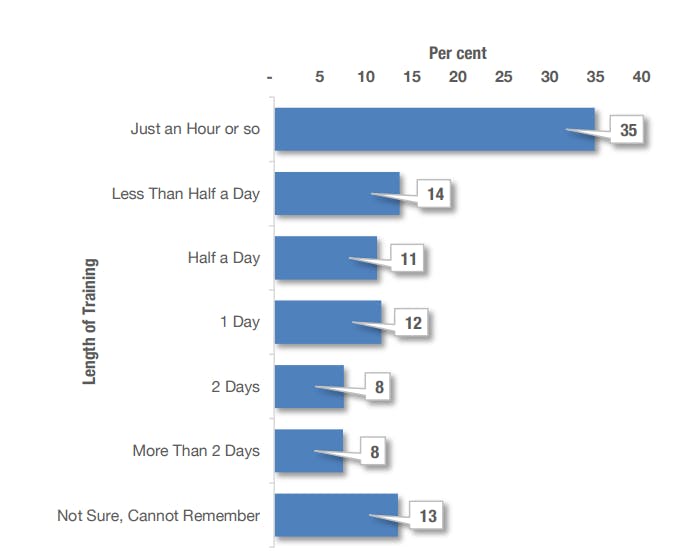

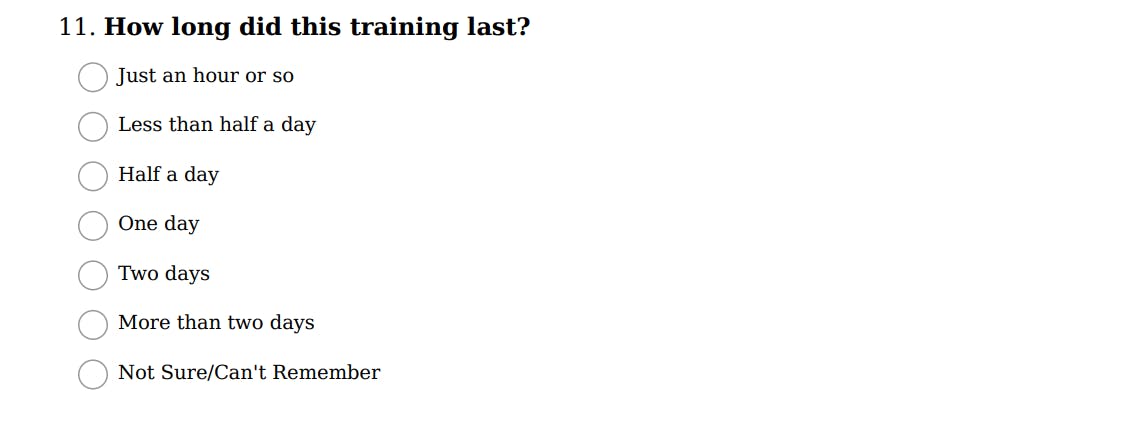

- One-in-three staff receive training for only an hour or so prior to working on SCO (35%). Those that received longer periods of training were more likely to say that they could cope with their workload and deal with non-scanning misuse.

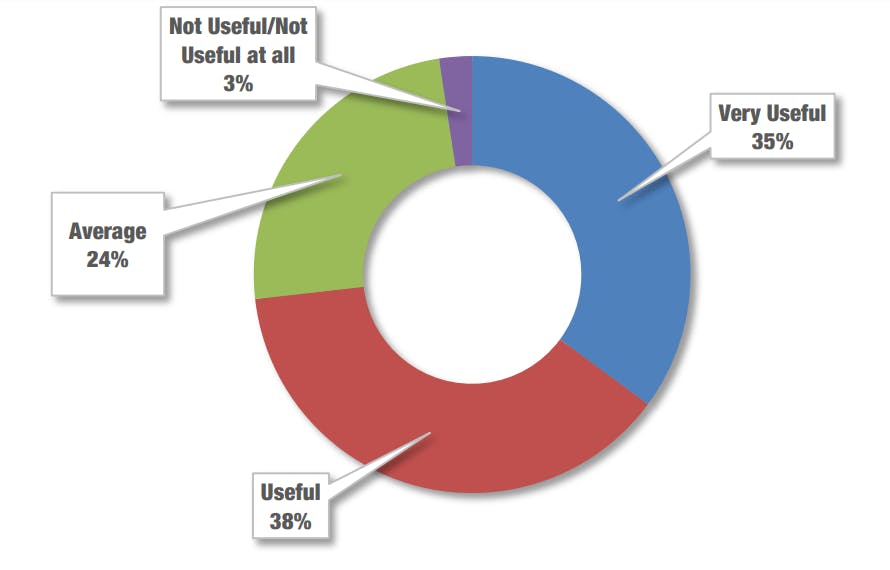

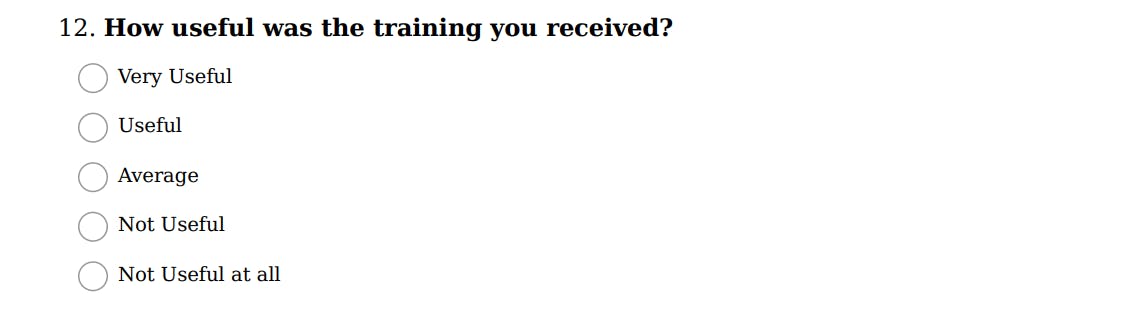

- Most staff who receive training find it useful – the length of training was associated with perceived usefulness – the longer the training the more useful it was viewed.

- Most training programmes include aspects of loss prevention although one-third stated that it did not (36%). When staff receive this type of training, they almost unanimously think it is useful (92%).

- Longer courses typically cover more SCO-related topics – the shortest programmes (just an hour or so) cover 30% fewer topics than those lasting the longest (2 days or more). Those who received more topics typically felt better prepared to cope with their SCO environment.

- Respondents thought training could be improved by including the following: more on loss prevention (e.g., greater awareness of, and capabilities to deal with, theft in general); dealing with technical issues, when SCO machines had faults/glitches; and customer service issues, including dealing with negative or difficult customers, how to better multi-task and be more vigilant, and how to effectively engage with customers.

The Self-checkout Operating Experience

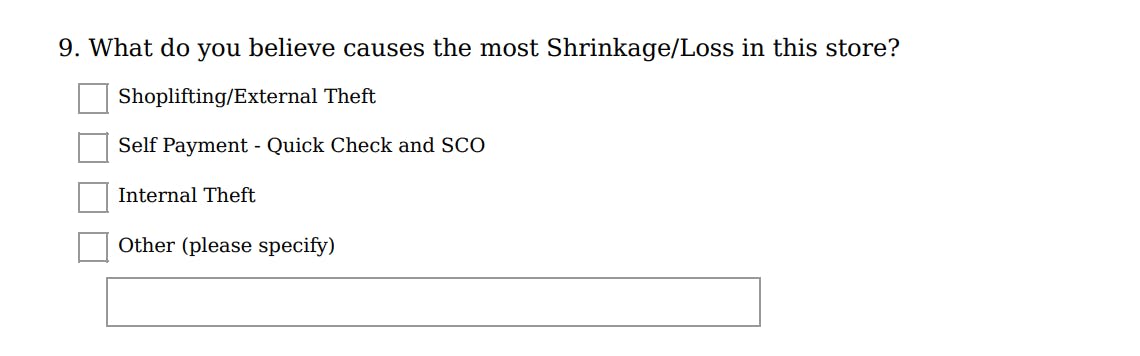

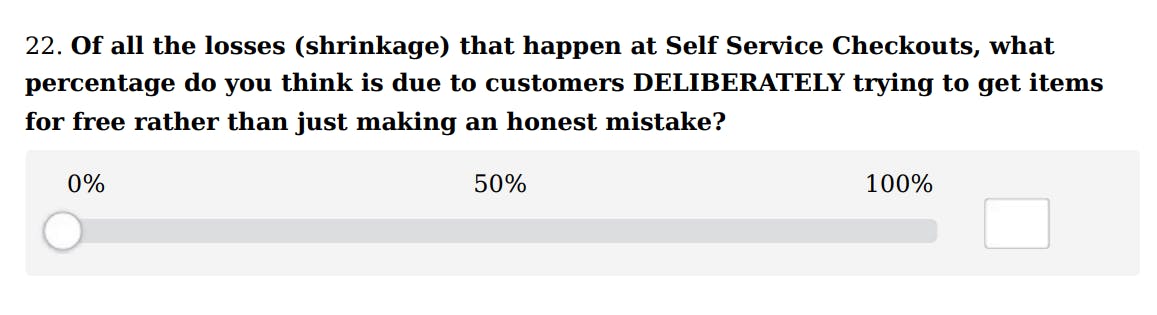

- On average, respondents believe that 51% of all SCO losses are caused by malicious customer behaviour.

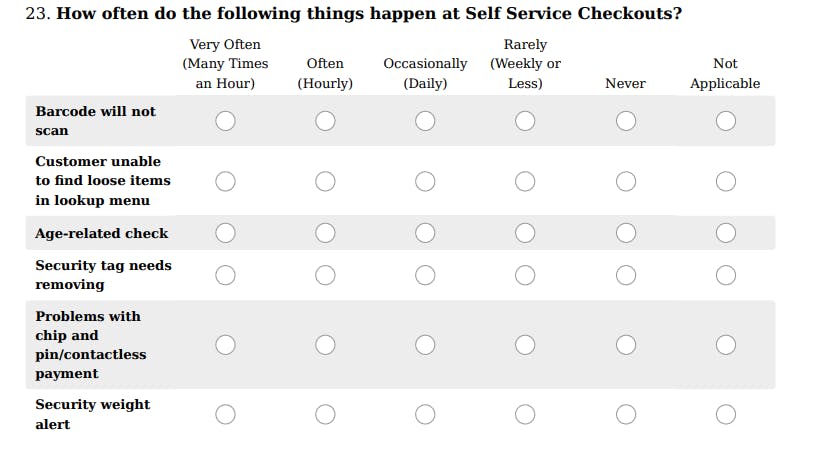

- Respondents stated that the most frequent process-related issues/alerts they experienced are agerelated checks, having to remove security tags, and dealing with security weight alerts – all occur many times an hour. They also noted that barcodes not scanning, problems with loose item look-ups and payment issues were also very regular events.

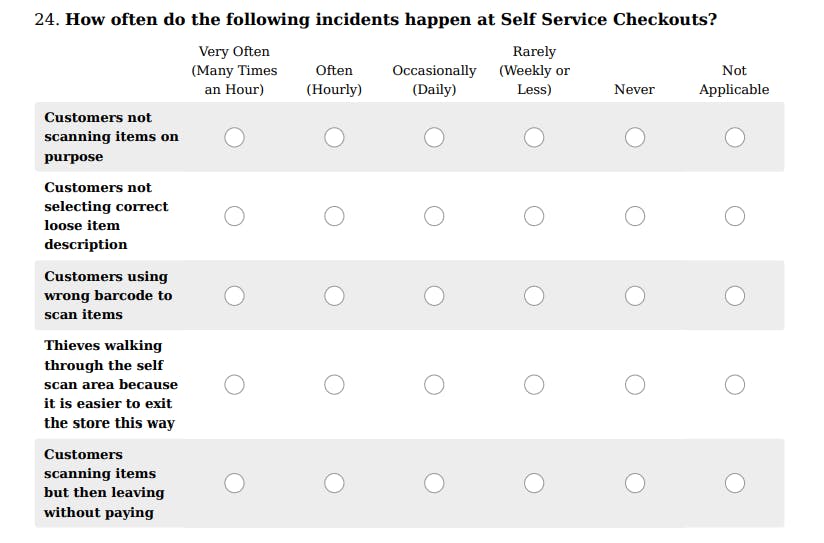

- When it came to the frequency of customer misuse, non-scanning, scanning but not paying, and misusing the product look-up function, were the top three, with at least one-third saying that they happen at least hourly. The data point clearly to staff believing that SCO misuse by customers is a very common event.

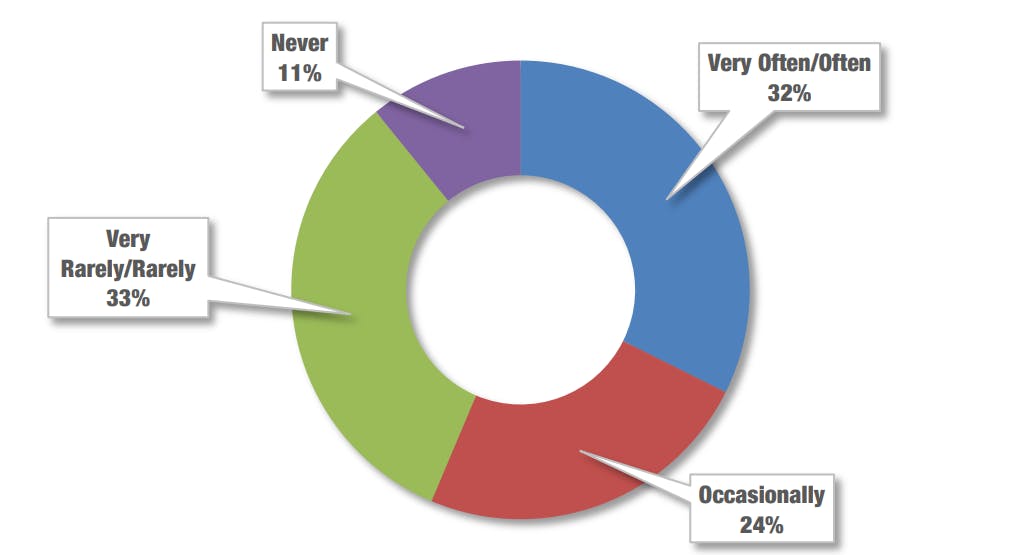

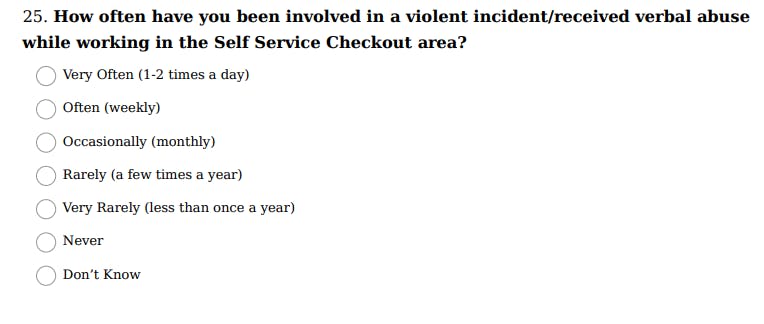

- One-third of staff (32%) stated that incidents of violence and verbal abuse occur very often or often in their SCO space (at least weekly). The survey also found that there was a correlation between how frequently violent and verbal abuse incidents were thought to be happening and the number of SCO machines that respondents had to supervise. Those with more SCO machines were more likely to say that incidents happen more often.

- Respondents were almost unanimous in their view that having additional staff to supervise the SCO area would be an effective or very effective intervention to deal with SCO problems (96%).

- SCO staff provided a series of recommendations for how their working environment could be improved, particularly focused upon three areas:

-- Guardianship: more staff, better trained, and greater management awareness of the issues affecting SCO.

-- Technology: more robust, up-to-date, and better designed SCO machines, combined with alerting to help identify problems; more reliable security weight checking; the ability to monitor and respond remotely, and some form of active exit control.

-- Design: more space to enable staff to have easier access and improved lines of sight of SCO machines.

Improving Retail Self-checkout

- The Value of Guardianship – the study has highlighted the importance of SCO supervision and put a spotlight on how retailers need to move from a ‘minimal possible’ staff operating model to one more focussed upon creating a ‘optimum control’ operating environment.

- Equipping Guardians I: The Importance of Training – the research identified the value of training and why it matters. Staff are keen to see their training include more on loss prevention-related issues, how to deal with problematic SCO technologies, and improving their customer service skills.

- Equipping Guardians II: Providing Technological Support – respondents were almost unanimous in expressing frustration with the quality and reliability of SCO technologies. They want to have more reliable, up-to-date, and better designed systems. In addition, they are keen to have a range of alerting options in place to help them do their work more effectively.

- Designing Zones of Control – SCO spaces need to be fit for purpose, having sufficient space to allow staff and customers to move freely and easily, encompassing clear and unambiguous ingress and exit controls. Above all, the design of SCO areas needs to ensure that it amplifies a sense of risk and enables staff to effectively play both a reactive and proactive role.

- Keeping Guardians Safe – retailers have a commitment to protect their staff and to ensure that they are creating a safe working environment for them. The survey has revealed worrying levels of violence and abuse, and respondents believe that in part, this is caused by frustrations generated by current staffing levels and inadequate/glitchy/poorly designed SCO technologies.

- Better Measuring the SCO Environment – more needs to be done to better measure a range of factors that affect the management and control of SCO spaces, not least the frequency of various types of SCO alerts; average SCO alert wait times; average SCO queue times; number of voided/abandoned/ walkaway incidents; and the number of incidents of violence and verbal abuse.

Learning From Front End Teams

This survey has provided a wealth of insights on how SCO teams try to manage and control the SCO environment. Above all, the research has highlighted how important people are in this process, but if they are to be successful, they must be given a manageable workload, receive high quality training, be supported with technologies that help them to focus upon the customers, transactions and events that matter, and operate in a space that is well designed, and above all, enables a zone of control to be maintained.

GETTING STARTED

The report includes 25 Talking Points for your Business – key learnings summarised into a series of ‘talking points’ that can be used to further explore how you can improve your SCO programme (Appendix I).

INTRODUCTION

Context

This is the second of three reports focussed upon developing a better understanding of the ways in which retailers are trying to manage and control the losses associated with various types of self-checkout systems (SCO)1 . The first report was focussed upon developing a better understanding of how retailers are currently operationalising SCOs, perceptions of their concerns about associated losses, and the extent to which they are trialling and deploying a range of interventions designed to address these issues2 . This second study is focussed upon adding to these insights through capturing and exploring the views and experiences of those at the ‘sharp end’ – the staff employed directly to operate and manage SCO environments.

These studies build upon earlier work carried out on behalf of ECR Retail Loss, including a study in 2018 that offered some of the first ever insights into the scale and extent of the problem of SCO-related losses3 , and a study in 2020 looking at how good design principles can be utilised to address some of these problems4 . In addition, ECR Retail Loss commissioned a study back in 2011 to look at the views of SCO supervisors at a time when the technology was just beginning to be deployed more extensively5 . That research found little evidence of staff experiencing or witnessing SCO misuse by customers and concluded that the overall impact on retail losses (as could ascertained at the time) was negligible. As will be seen in this new research, a very different picture is now evident of the impact SCO is having on retailing and those tasked with its management and control.

Adoption

While SCO technologies are not necessarily a recent development within retailing – early examples of enabling consumers to scan and pay for their items without recourse to a member of retail staff can be seen in the late 1980s/early 1990s – in the last 10-15 years the pace of development and adoption has quickened considerably, especially in the Grocery sector6 .

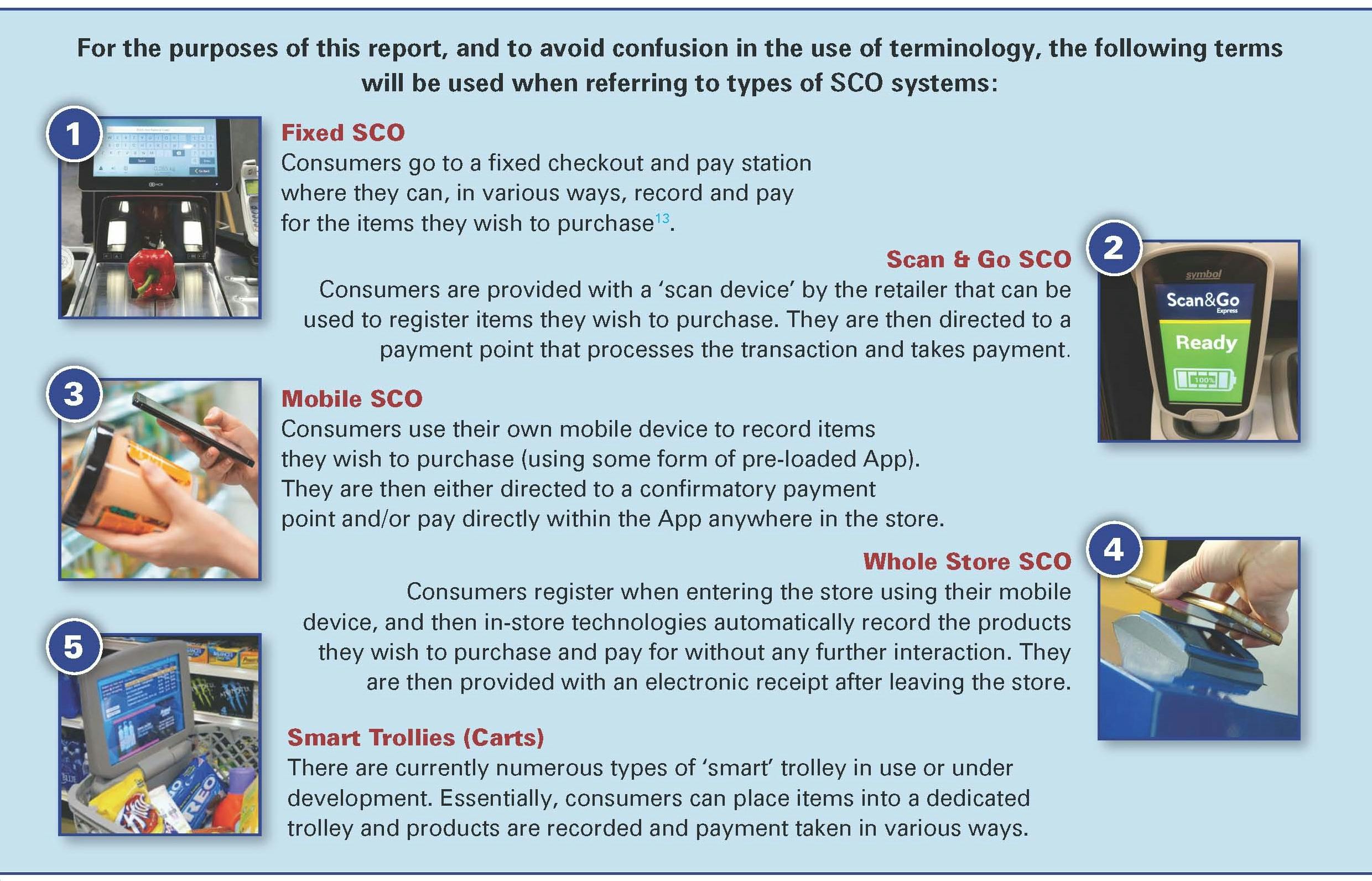

In addition, there are now far more ways in which SCO is being realised in a broader range of retail environments. As outlined in the first report from this three-part study, while Fixed SCO machines remain the most dominant type of system currently in operation, retailers are now also offering their shoppers a range of alternatives, including Scan & Go (where the consumer is provided with a device to scan items they wish to purchase), Mobile SCO (where the consumer uses their own hand-held device to scan and in some cases pay for their items), Smart Trollies/Carts, some of which can automatically detect items placed within them, and Whole Store SCO systems, where once a shopper has registered and scanned themselves into a store, they can pick up items and leave without any need for further scanning or interaction with a payment point7 .

Issues

As discussed in other ECR reports, the introduction of SCO systems has often afforded retailers an opportunity to considerably reduce their labour costs and provide some consumers with greater convenience and choice in how they can check out. But recent studies have also documented how they can also increase retail losses, primarily due to the way in which they generate a wide range of opportunities for both malicious and non-malicious events to occur. For instance: customers accidentally or deliberately not scanning some of the items they wish to purchase; users misrepresenting one weighted product for another (the grapes for carrots ‘trick’); using pre-printed barcodes to undervalue more expensive items; and carrying out ‘walk-aways’, where a customer scans all their items but then does not pay for them. Not only do these types of incidents generate direct losses for retailers, but they can also have a negative effect upon in-store stock file accuracy (they often happen without a retailer becoming aware until their next stock audit), which in turn can generate indirect losses through lost sales due to out of stocks and increases in product wastage8 .

A 2018 ECR Retail Loss report estimated that for each 1 per cent of retail sales processed through Fixed SCO, a retailer will suffer an increase in unknown loss of 1 basis point. This means that if 50% of sales value goes through this type of system, then a retailer could see an additional loss of 0.5% of their retail sales. With some estimates suggesting that unknown losses (shrinkage) for a Grocery retailer might be in the region of 1.50% of retail sales per year, this would represent a 30% increase in losses. More significantly, estimates for other types of SCO system losses were even more concerning – Scan & Go and Mobile could see the rate of losses rise higher, possibly as much as 7-10 basis points of loss for each 1% of transaction value9.

Management

Despite growing awareness of the scale of losses increasingly associated with SCO, the predominant trend is for retail to introduce more of these systems – bringing them in to different retail environments, such as apparel, and extending the range of options available, such as the use of Mobile SCO10. As such, the question is no longer whether retailers will continue to use SCO, but how can they be better managed and controlled to ensure that they do not become an unacceptable drain upon profitability, particularly when they account for a growing proportion of sales?

As the first report from this tripartite study identified, retailers are now experimenting with, installing, and adopting a plethora of interventions11 focussed upon managing the SCO environment. These have largely been focussed upon key points within the shopper journey: registration; entering the store; selecting product in-aisle; the checkout area; and exiting the store. In addition, they have coalesced around four broad themes: the application of various types of technologies, such as video technologies and weight-based interventions; changes in the way in which guardianship is delivered, such as changes to the selection and training of SCO supervisors; adjustments to store processes, such as closing Fixed SCO machines in off peak times; and changes to the design and layout of stores and SCO-specific environments, such as the use of Corrals and exit control gates12.

The SCO Supervisor Role

The purpose of this second report is to capture the views and experiences of those tasked with working in the SCO environment – often referred to as SCO supervisors or assistants. For the most part, these staff are employed to provide oversight and assistance to customers who are checking out via Fixed SCO machines and those using the various types of Scan and Go systems in operation.

Typically, they have responsibility for several Fixed SCO machines and routinely respond to alerts and problems that customers generate and experience (such as age verification and security weight-check issues). In addition, there is an expectation that they will act not only as a form of deterrence to SCO misuse by customers (such as not scanning items), but also respond when they become aware of customers engaging in malicious and non-malicious behaviours. As such there is an expectation that they will be both reactive (fix problems as they occur) and proactive (stop theft and errors occurring through their presence and oversight) in this space.

In terms of Scan and Go type systems, these staff are primarily required to ensure customer problems with the technology and checkout process are quickly resolved and to perform system-generated audits of a select number of customers. For the most part these are partial audits where an algorithm decides which customer should be checked and how many items in a customer’s trolley/cart/basket should be scanned for accuracy. For instance, the system may require a member of staff to scan five items in a customer transaction supposedly containing 30 items. Which items are scanned is for the member of staff to decide and previous research has shown how relatively unreliable this approach can be in terms of identifying baskets/trollies/carts that contain scanning errors13. In many respects, this is a very difficult task for staff to perform – not only in terms of deciding which products to scan, but also managing what can be seen as a ‘challenging’ interaction with a customer (in effect the audit is suggesting you may have not scanned all the items you wish to purchase, and we need to check your accuracy and by implication honesty).

Study Objectives

This study sets out to capture various aspects of the SCO supervisor experience via an online survey. The study was particularly focused upon their experiences of the following:

• The length of time they have been with the company and worked on SCO.

• Aspects of their working environment, including: the length of their shift, the number of SCO machines they typically have responsibility to oversee (and what they consider to be the optimum number); whether they worked alone or with others; the extent to which they feel able to effectively manage the SCO environment; and what they see as their primary role in this space.

- The extent to which they have received training before working on SCO, including: its duration; content; whether it covered loss prevention-related topics; their overall assessment of its value, whether it properly prepared them to deal with non-scanning behaviour; and recommendations for how it could be improved in the future.

- Their assessment of the extent to which various types of SCO-related alerts and problems occur and how much of the loss is due to malicious customer behaviour.

- How effective or not a range of interventions might be in helping to manage the problem of loss.

- The extent to which incidents of violence and verbal abuse occur.

- Finally, recommendations for how their SCO working environment could best be improved.

As detailed earlier, much of the research to date has been focused upon either measuring the impact of SCO on retail profits or better understanding the approaches and views of retail organisations deploying them. This study seeks to add to this landscape of understanding by adding the views and experiences of those tasked to operate these systems. As such it is offers an important contribution to better understanding the impact, management, and control of SCO systems in retail environments.

METHODOLOGY

Background

The aim of this study was capturing the views and experiences of those employed to supervise SCO spaces in retailing. Globally, there is likely to be hundreds of thousands of retail staff that are employed to work on SCO and so it was important to develop a methodology that could reach out to this group in a way that was both manageable and secured a good degree of validity in the data. One option was to make a link to an online survey available through various social media sites and allow respondents to self-identify as both working in retail and supervising SCO systems. While this could potentially generate a very high number of responses, it could also prove challenging in terms of verifying the validity of the responses.

It was decided, therefore, to develop an approach that invited retail companies to participate in the research that were known users of SCO and were prepared to give access to their staff. While this immediately limited access to the survey (the retailers effectively acted as gatekeepers), it did enable the researcher to have a much higher degree of control over who was responding to the survey. Two retailer recruitment approaches were adopted: 1) companies that had contributed to the ECR Retail Loss working group focussed upon the customer checkout experience were approached to ascertain whether they would be interested in participating in the research; and 2) a message was posted on the Linked-in business forum advertising the study and asking any retailers currently using SCO systems and wishing to participant to get in touch. While there was no restriction in terms of where the retailer operated – the research instrument could be translated into any language – the study was focussed mainly towards the Grocery sector as this is where most SCO systems have been deployed to date.

Data Collection

The process of negotiating access with possible retailers began in early 2022, with the bulk of data being collected between June and October 2022. In total nine retailers eventually agreed to take part – two based in the US, four in the UK, one in mainland Europe and two in Australia. All respondents can be regarded as large retailers; collectively they had total sales in 2021 of €292 billion, with a total of nearly 12,000 stores and together employing approximately 1.4 million staff. As with very many studies focussed upon retail businesses, the researcher’s access and capacity to obtain a sample of employees was limited to those companies that were willing to participate. As such, the participating retailers cannot be regarded as representative of the countries where they operate – their names have been excluded from this research to protect their anonymity. However, the research did receive a relatively large number of responses, which has enabled a wide range of insights to be drawn from this data.

Participating retailers employed several strategies to encourage staff working on SCO to complete the survey. Some were provided with publicity material by the researcher displaying a QR code that linked to an online survey – participants could then use their own mobile device to complete the survey. Another retailer advertised a link to the survey via a popular in-company chat forum, while another gave store staff working on SCO access to a computer where they could complete the survey. At all times, participating retailers were encouraged to stress that this was an independent study being undertaken by a British University.

By the end of the data collection phase, useable responses had been received from 6,170 respondents, making this the largest survey ever carried out by ECR Retail Loss. Return rates varied considerably between retail companies with a high of 3,072 and a low of 90. A range of statistical tests were deployed to analyse this data using the SPSS programme – reference to any differences between responce groups are only included when shown to be statistically valied. Details of these tests can be found in the endnotes.

It is important to note that while there are these various types of SCO system in operation across retail businesses, including those taking part in this study, to keep the questionnaire manageable for respondents, virtually all the questions relate specifically to staff experiences of working on Fixed SCO systems only. No doubt as SCO continues to evolve, it will be important in the future to also collect the views of those staff that have responsibility for other types of system, such as Scan and Go and Mobile SCO.

All currency values are quoted in Euros using an exchange rate calculated on the 21st October 2022. In some of the tables and charts presented below, percentages may add up to more than 100% due to rounding. A copy of the questionnaire used can be found in Appendix II.

FINDINGS

Introduction

The findings from this study have been organised in to three sections:

• The first considers the actual working environment for SCO supervisors, including how long they have worked for the business and on SCO, shift lengths, the number of machines they must supervise (and feel able to supervise), the extent to which they believe they can cope and are sufficiently well prepared to deal with SCO misuse.

• The second section then looks at their experience of training, including whether they had received any, what was included, whether issues of loss prevention were covered, how they rated their training, and suggestions for how it might be improved in the future.

• The final section then provides an extensive review of their experiences of working in a SCO environment, including their estimates on the frequency with which various types of problems and alerts occur, how they rate various types of interventions that could be used to help control the SCO environment, the frequency of incidents of violence and verbal abuse, and finally, their suggestions for how their SCO space could be improved.

The Self-checkout Working Environment

This first section begins by summarising the working experience of respondents – how long they have been with the company, the length of time and frequency that they work on SCO, shift lengths, number of SCO machines they must supervise and would prefer to supervise, their perceived capability to manage them, and what they consider to be their primary role.

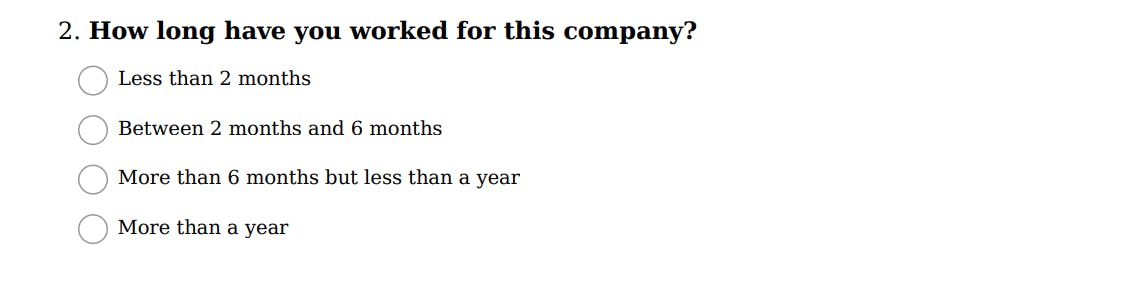

Length of Time with the Company

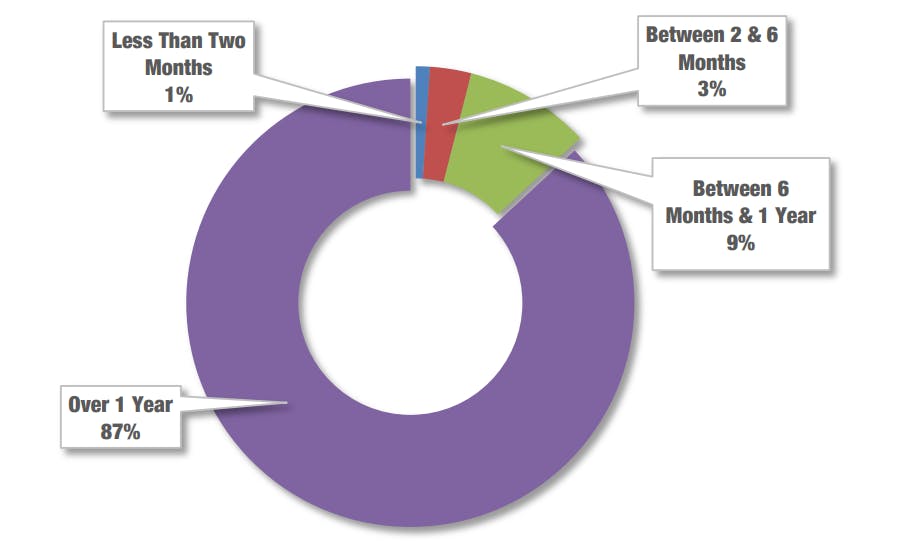

A common concern raised about the management of SCO environments, particularly when they were first introduced, was the extent to which retailers were perceived as putting their most inexperienced or least able staff in these roles, reflecting a lack of prioritisation compared with other store tasks. It was important therefore to begin by getting a better understanding of the profile of the staff employed in SCO. Detailed in Figure 1 is the length of time that respondents said that they had been with the retailer, ranging from less than two months through to over a year.

Figure 1 Length of Time Worked for the Company

Most respondents in this survey had been with their current employer for a considerable period – 87% stated that it was at least a year. Only 1% were new starters (less than two months) with the remaining 12% ranging from two months to a year. While it was not possible to compare longevity of service in SCO with other store functions, this suggests that there is little evidence that those with the least time in the business are being placed in SCO.

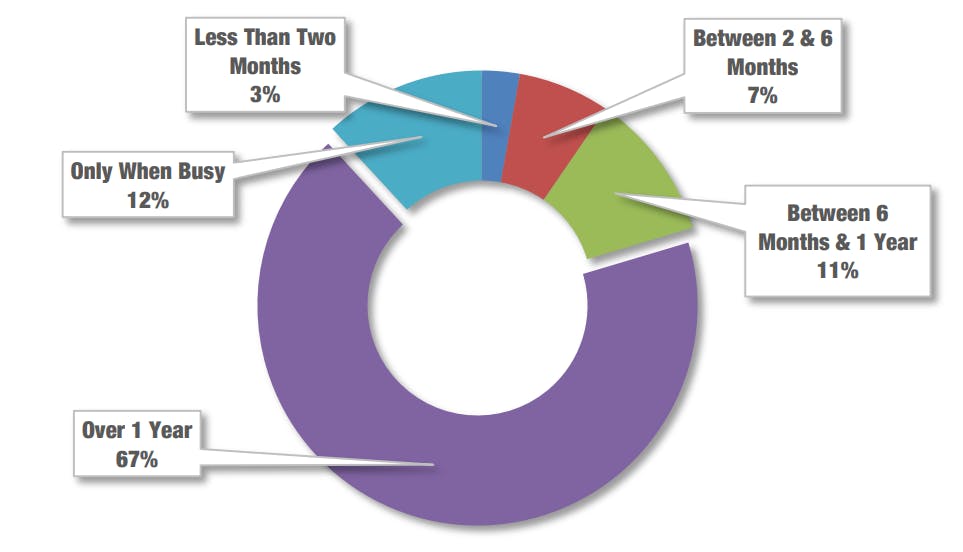

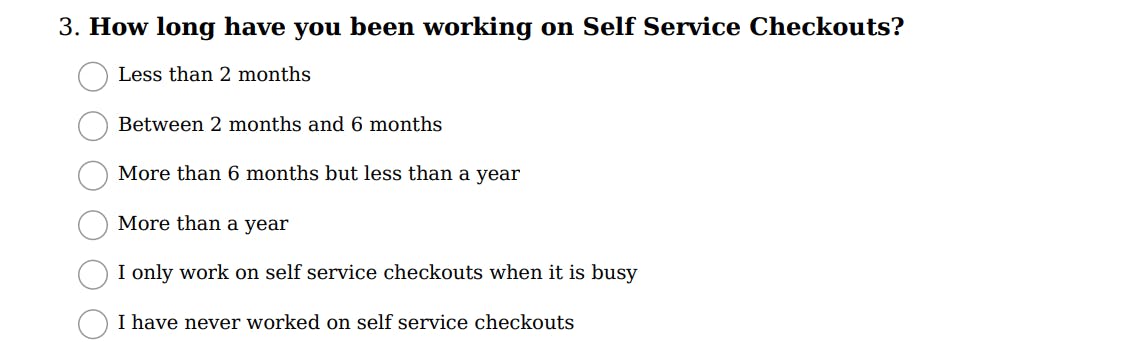

Length of Time Working on SCO

This is confirmed with the data on the length of time staff had worked directly on SCO (Figure 2). As can be seen, two-thirds of respondents to this survey had a considerable amount of experience working on SCO – over one year (67%). In addition, a further 11% had been working on SCO for at least six months.

Figure 2 Length of Time Working on SCO

Only a relatively small proportion stated that they had worked on SCO for less than six months (10%) although a slightly larger proportion regarded themselves as only working on SCO when it was busy (12%).

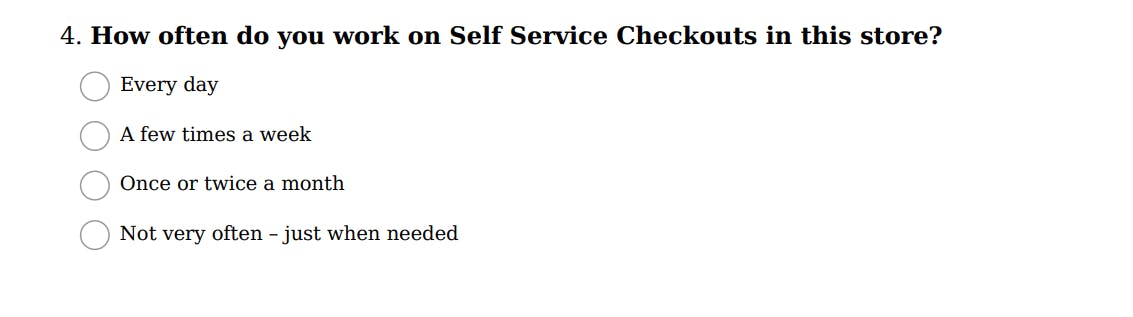

Frequency of Working on SCO

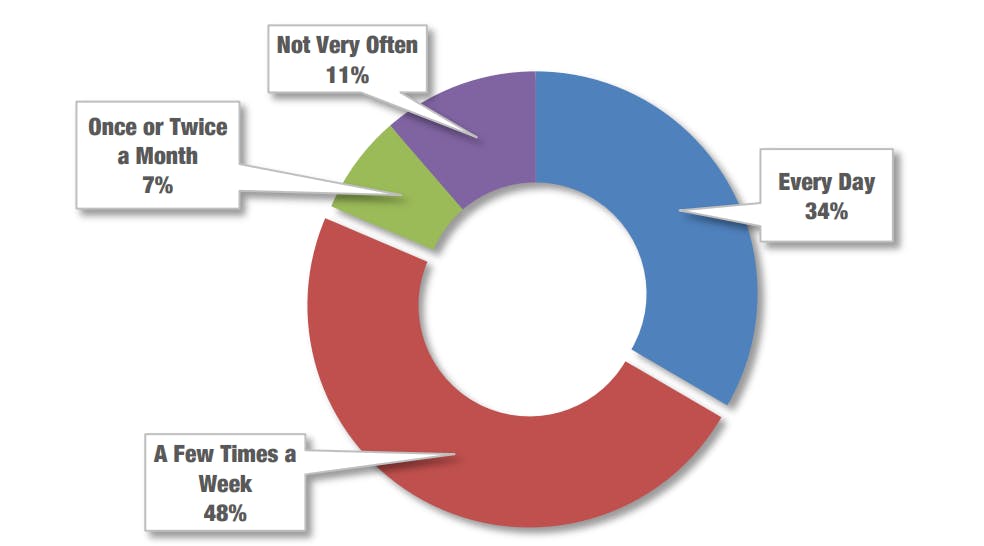

The final indicator on the profile of staff employed in SCO relates to the frequency with which they worked in this area (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Frequency of Working on SCO

The most common response was ‘a few times a week’ (48%) with a further one-third suggesting that it was something they did every day (33%). For the remainder, SCO work was something they only did once or twice a month or even less (18%).

Taken together, the data suggests that for the retailers taking part in this survey, they are typically deploying staff that have been with the company for a good period, have a considerable amount of experience in the SCO environment, and operate there on a very regular basis

Typical SCO Shift Length

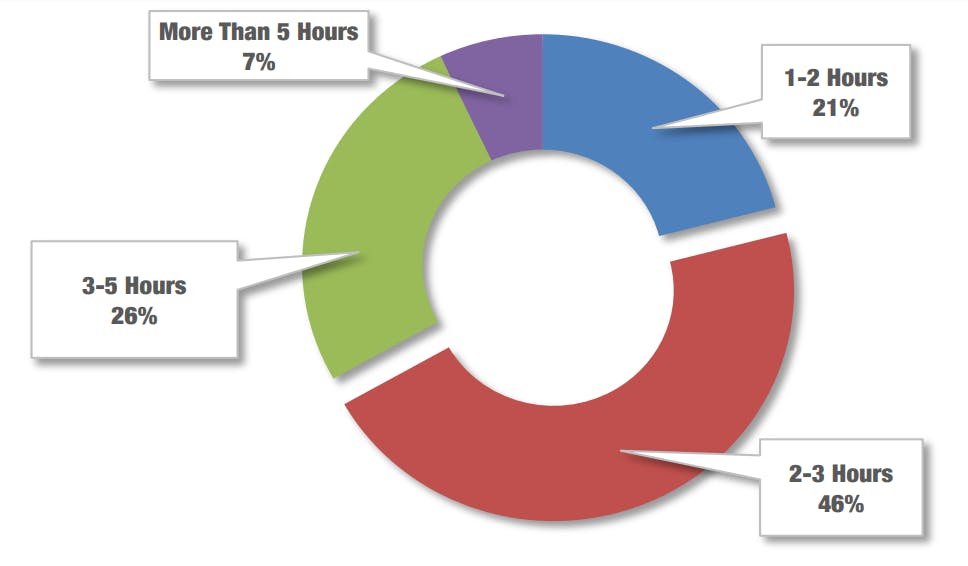

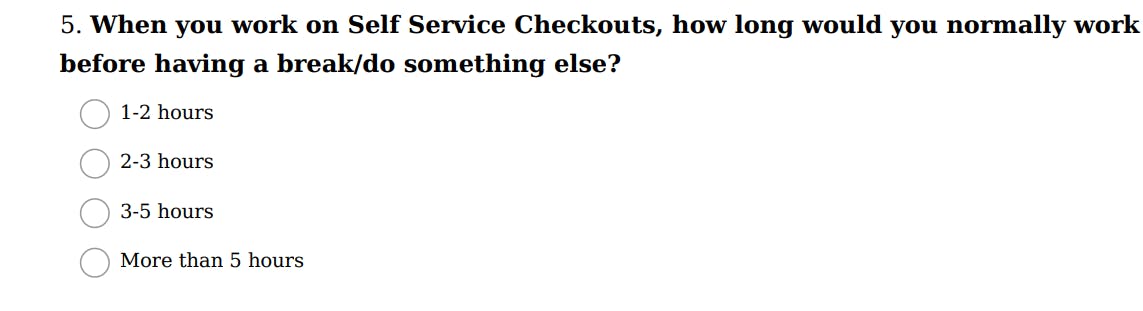

Respondents were then asked how long a typical shift working on SCO lasted (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Typical Length of Shift

As can be seen, 46% of respondents said that their shift was normally 2-3 hours long before they took a break or were assigned to another task. However, a significant proportion – just over one-quarter (26%), suggested that their shift was longer – between 3 to 5 hours. In contrast, one in five respondents worked a shorter shift – just one to two hours before they were relieved of their SCO supervisory duties (21%). For a small minority (7%) their SCO shift was over 5 hours in length. The impact of shift length will be considered in more detail at various stages in the rest of the report.

Number of Staff Working on SCO

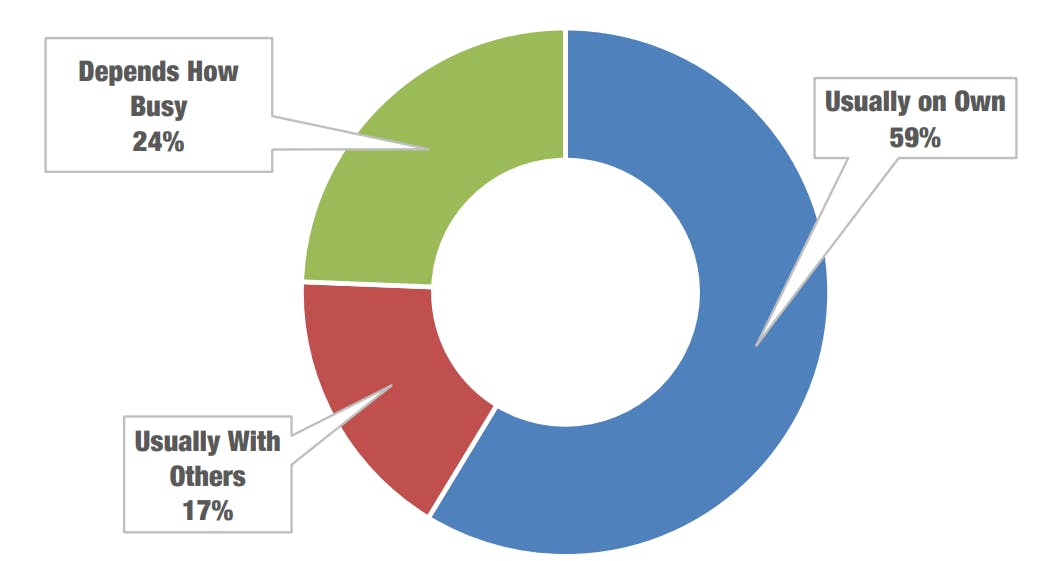

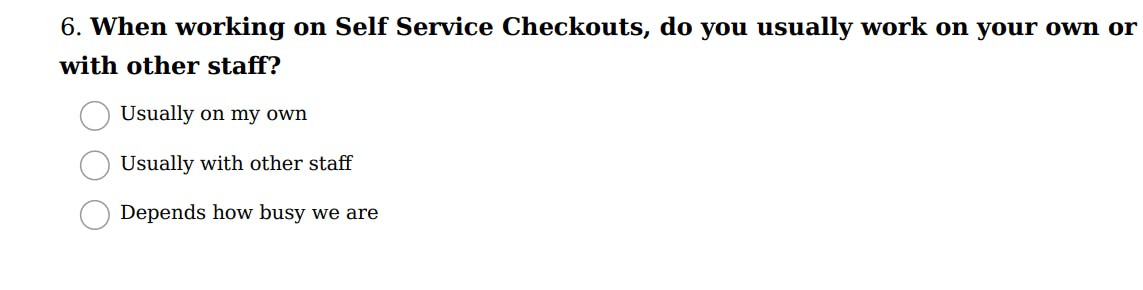

Figure 5 provides a summary of the extent to which respondents typically work on their own or with others or whether this varies depending upon how busy the SCO area is.

Figure 5 Number of Staff Supervising SCO

Most respondents to this survey stated that they usually worked on their own (59%) with a further one-quarter (24%) stating that it depended how busy they were, and the remainder tending to work with others in the SCO area (17%). Of those that did work with others, 56% said one other; 31% worked with two and 13% more than two staff.

Ratio of SCO Machines to Staff

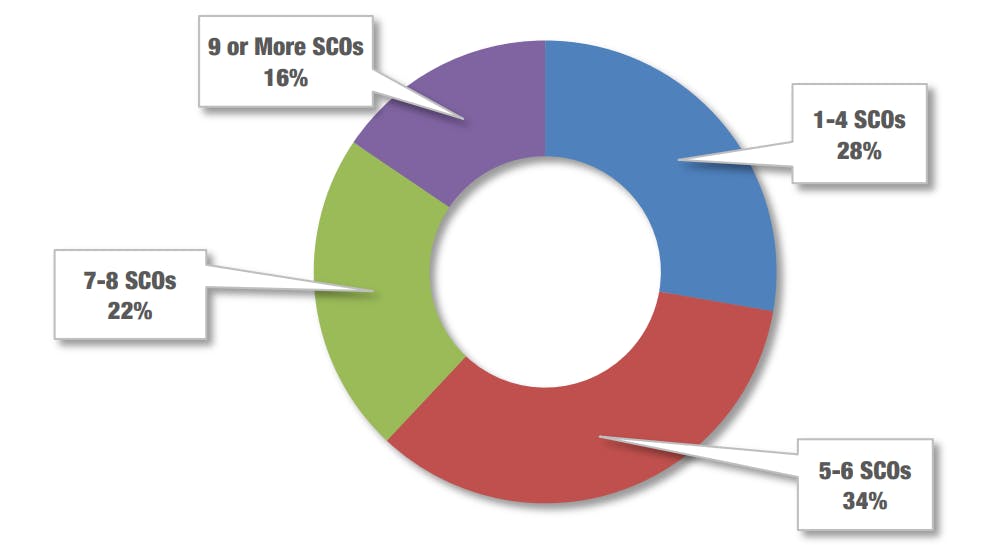

One of the perennial questions relating to Fixed SCO is the number of machines allocated to a member of staff to supervise. Figure 6 focusses only upon responses from those that stated they worked alone and summarises the number of SCO machines they said they had to monitor.

Figure 6 Number of SCO Machines Supervised

As can be seen, the most common ratio is 5-6 SCO machines per member of staff (34%), with a further 28% stating that it was lower – 1-4 SCO machines. However, one in five respondents (22%) suggested that they had to monitor between 7-8 SCO machines alone, while 16% had an even greater workload – 9 or more SCO machines. Taken together, 38% of respondents have responsibility for 7 or more SCO machines.

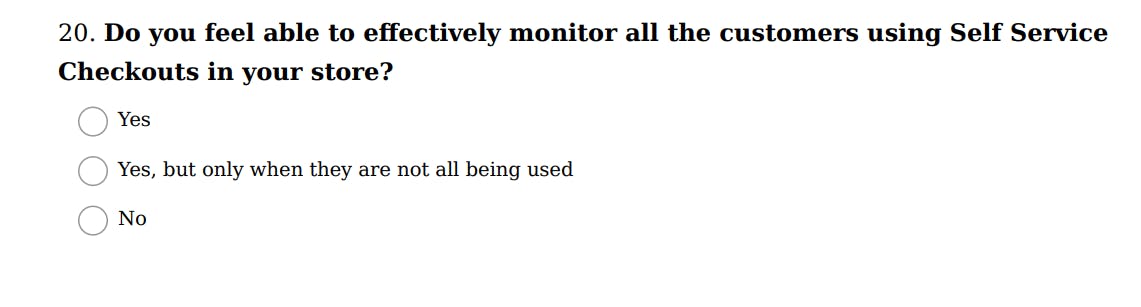

Capability to Monitor Current Number of SCOs

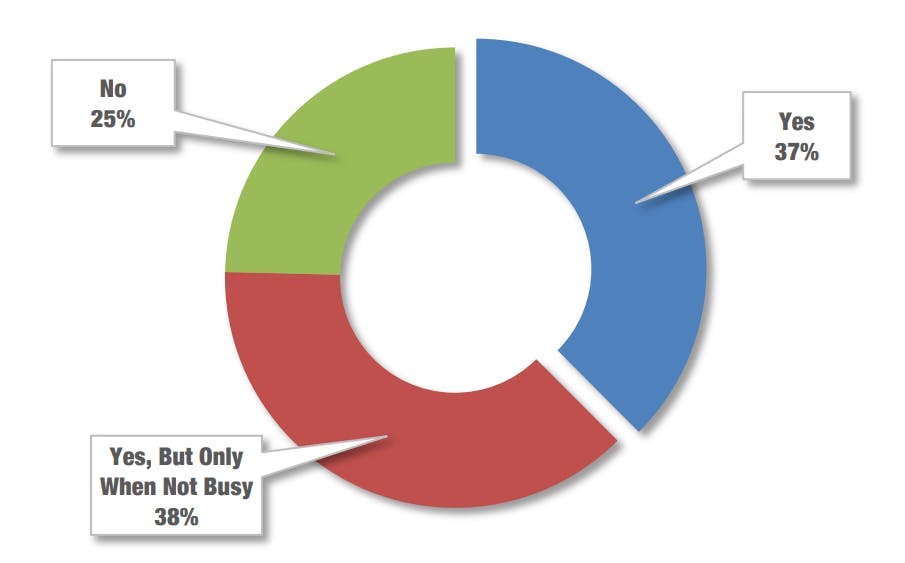

Perhaps more important than the ratio of machines to staff is the extent to which employees feel able to monitor the number they have been allocated (either alone or working with others), particularly as the ratio statistic does not take account of the volume of transactions being processed through the SCO machines. For instance, one member of staff may be allocated four SCO machines to supervise but collectively only process a relatively small number of transactions in any given day. For another staff member, the same ratio may not only have a greater volume of transactions, but also their velocity may be very different (higher peaks and troughs in activity for instance). Figure 7 captures the extent to which staff believe they can effectively monitor the number of machines they have been allocated.

Figure 7 Perceived Capability to Monitor SCO Machines

The largest proportion of respondents believe that they can only cope when it is not busy (38%), with a further 25% stating they do not feel capable of monitoring all the SCO machines for which they have responsibility. Taken together the data suggests that two-thirds of SCO staff either cannot cope or can only cope when it is not busy in their SCO area. On the flip side, one-third (37%) do believe that they can manage with their current allocation of SCO machines.

The data also shows that there is a relationship between the ability to cope and the number of SCO machines allocated – the percentage of those who state that they can cope reduces as the ratio of SCO machines increase – 47% of those allocated 1-4 machines compared with only 26% of those who must supervise 9 or more SCO machines.

Optimum Number of SCOs to Manage Effectively

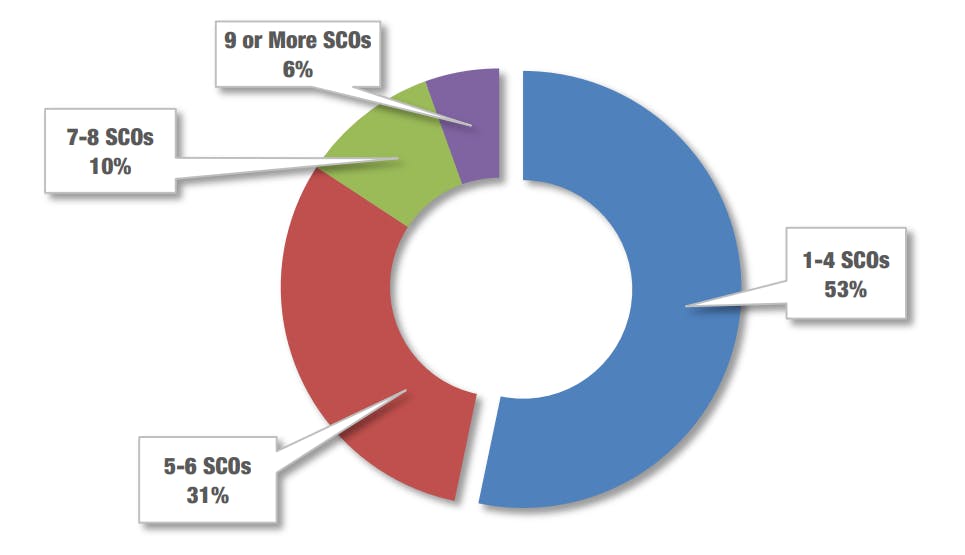

The survey then went on to ask respondents how many SCO machines they think they can effectively manage at any one time (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Preferred Number of SCO Machines to Supervise

Most respondents believe that between 1-4 machines is the optimum number (53%) although a significant proportion (31%) believe that they can cope with between 5-6 SCO machines. In contrast there was little support for supervising many more machines – 10% thought that 7-8 machines would be manageable, while just 6% were of the view that they could deal with 9 or more SCO machines.

As mentioned earlier, while the ratio statistic is probably a reasonable starting point for considering staffing levels, three other factors need to be considered – the volume and velocity of transactions across time that take place in any given SCO environment, and the extent to which the SCO system generates alerts. For instance, retailers with no age verification requirements nor a security weight checking component, will likely generate far fewer alerts than retail environments where they are in operation. More indirectly, the quality and age of the SCO machines is also a potential factor – findings presented later in this report will show high degrees of staff frustration around this issue and how it can generate additional work and customer friction. It could be that the frequency of system faults could also be another factor utilised to calculate staffing levels in the SCO space.

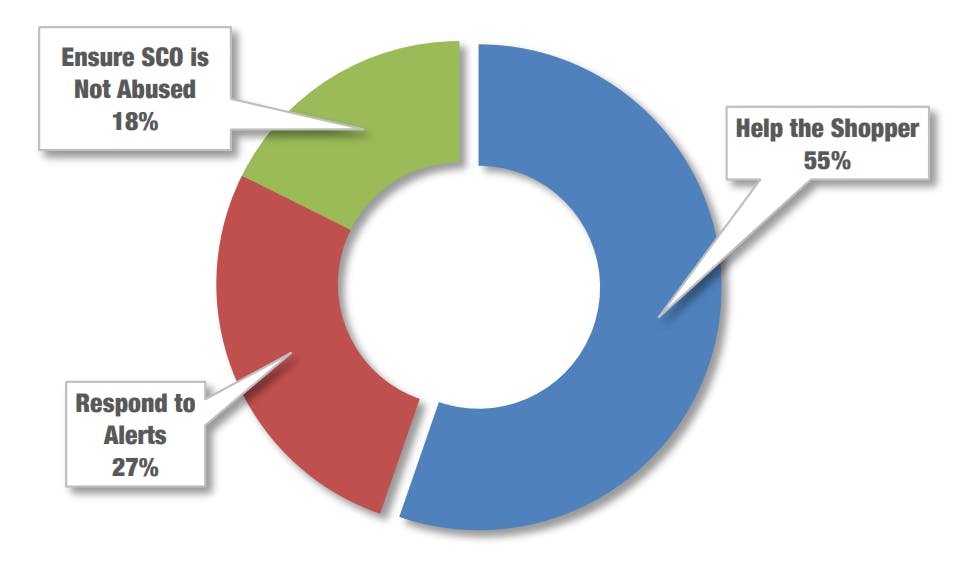

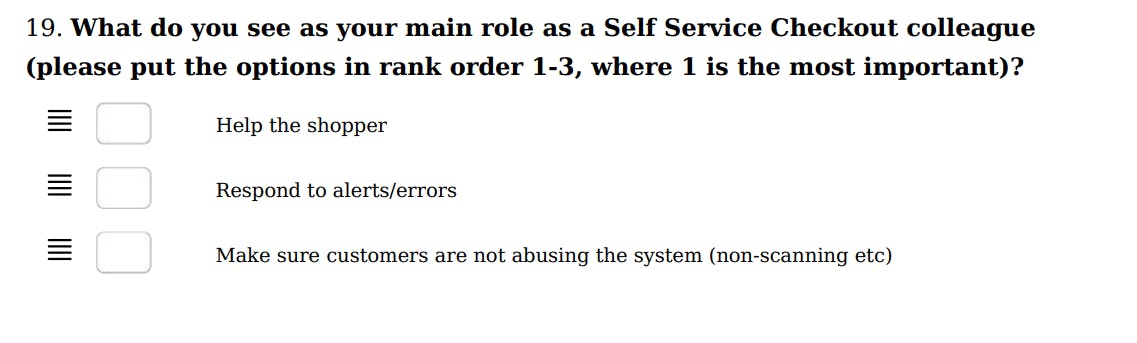

Main Role When Supervising SCO

The final question in this section looks at how respondents view their overall role in the SCO space, asking them to rank three factors in order of importance: help the shopper, respond to alerts, and ensure the SCO system is not abused by customers (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Most Important Role When Supervising SCO

As can be seen, most respondents ranked helping the shopper as their number one priority (55%), followed by responding to alerts (27%), and finally trying to ensure SCO is not abused (18%). Of course, the three areas are intrinsically linked – responding to alerts is a key part of helping the shopper navigate through the SCO experience, while at the same time enabling staff to interact to minimise the risk of misuse. In many respects, therefore, this is a positive outcome, with most respondents identifying their key role as helping the shopper.

Self-checkout Training

The next section of the report focusses upon the issue of training, looking particularly at the following: • Whether any SCO-related training had been received.

- How long the training lasted.

- How useful it was thought to be.

- Whether the training included issues relating to loss prevention and views on its value.

- Topics covered by the training.

- Ideas for how the training could be improved.

Received Training

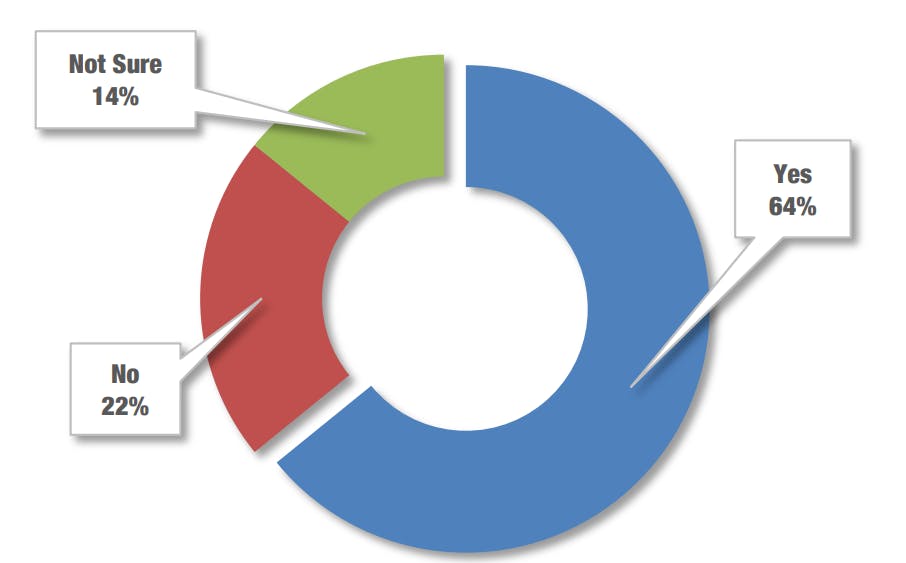

The first question related to whether respondents thought that they had received any form of training before they worked on SCO (Figure 10).

Figure 10 Received Training on SCO Supervision

Most respondents were of the view that they had received some form of training (74%), although over onequarter said that they had not or were unsure if they had received any training (26%).

There were some marked differences between these two groups. Firstly, those who only worked on SCO when it was busy were more likely to have not received any training14. Secondly, and perhaps unsurprisingly, those that had not received any training (or were not sure that they had) were much less likely to say that they felt able to monitor all the customers using SCO – 42% of those that had received training said that they could, while only 24% of those that had not received any training were of this view15.

Thirdly, it was also the case that when asked to consider how frequently a range of malicious activities were happening at SCO (customers not scanning on purpose, not selecting the correct loose item look-up, using the wrong barcode, thieves walking through the SCO area, and customers scanning but not paying for their goods), those that had not received any training (or were unsure whether they had) were significantly more likely to state that they occurred more frequently than those that had received training16. One interpretation of this is that trained staff are more likely to act as a deterrent to SCO abuse by customers.

Length of Training

Those that had received some forms of SCO-related training were then asked how long it had been, ranging from just an hour or so through to more than 2 days (Figure 11).

Figure 11 Length of SCO Training

Nearly two-thirds all respondents said that their training had been half a day or less (60%), with one-third stating it had only lasted for an hour or so. In contrast, one in eight said that they had received a full day of training on SCO (12%), while 16% had received two days or more of training. This is a very different profile of training compared with the 2011 ECR survey of SCO supervisors, where two-thirds of respondents stated that they had received at least one day of training (66%)17. For the most part SCO staff are now provided with a much shorter training experience.

The length of training received was associated with how well-prepared respondents felt they were to deal with non-scanning misuse – the longer the training the more likely they felt well prepared to deal with it (74% of those that had received an hour or so of training, compared with 88% of those that had received one day or more of training)18.

This trend was mirrored with how well respondents thought they could monitor all the customers using SCO – the shorter the training programme the less likely they were to feel able to cope (35% of those receiving only an hour or so of training, compared with 53% of those receiving a day or more of training19.

Usefulness of Training

The survey went on to ask recipients of any form of SCO training how useful they thought it had been (Figure 12).

Figure 12 Usefulness of Training on SCO

As can be seen, overall, respondents were positive about the training they had received: nearly three-quarters (73%) were of the view it was very useful or useful, while a further 24% were of the view it was only average. Just a tiny percentage did not consider their training to be useful (3%).

There was a correlation between the length of training and the likelihood to regard it as useful – the longer the training, the more useful it was – 63% of those receiving just an hour or so of training thought it very useful or useful, whereas 89% of those receiving 2 days or more of training thought the same20.

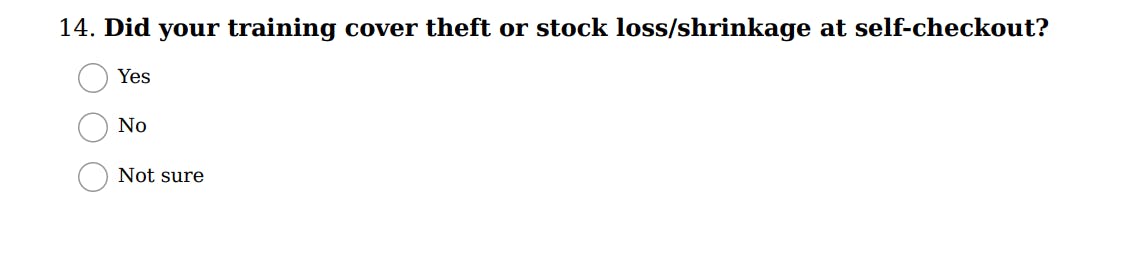

SCO Training and Loss Prevention

Those that had received some form of SCO training were also asked whether it had covered topics relating to loss prevention (Figure 13).

Figure 13 Received Training on Loss Prevention and SCO

A majority of those receiving some form of training said that the topic of loss prevention had been included (64%) although a sizeable minority, over one in three, said that it had not (36%). Those who had shorter periods of training were more likely to say they had not received training on loss prevention: 81% of those that had not received any loss prevention training had received half a day or less of training21.

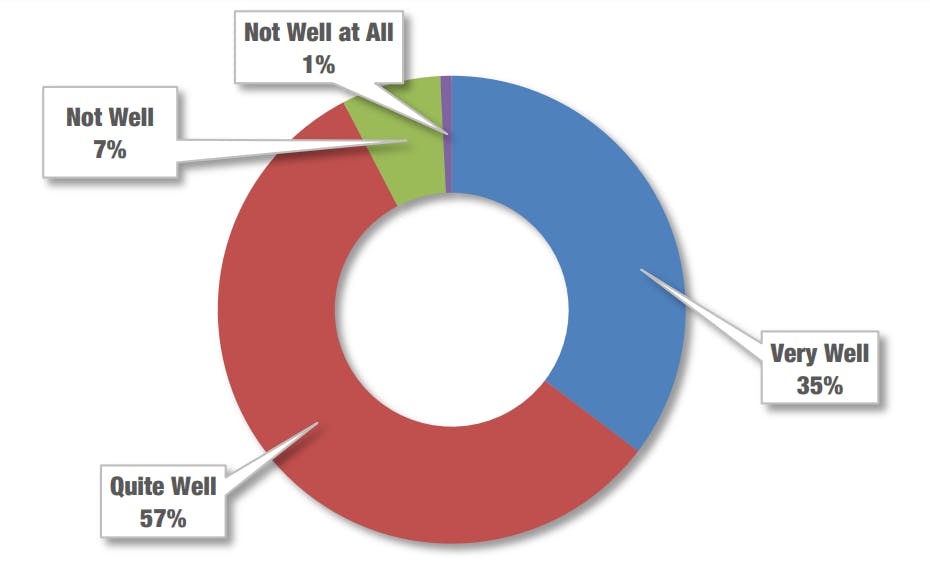

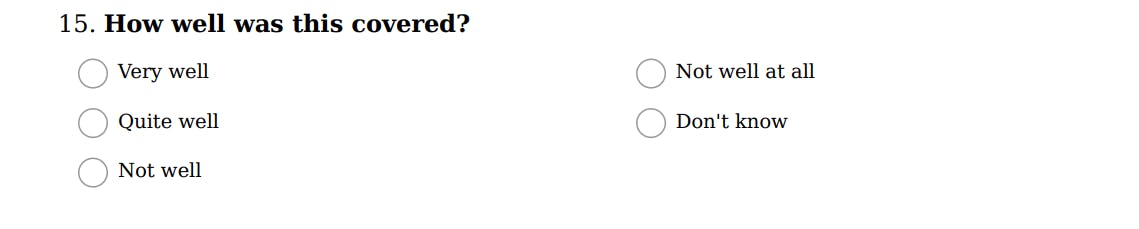

Perception of Loss Prevention Training

The respondents that had received any form of loss prevention training were asked to review how well they thought the topic had been covered (Figure 14).

Figure 14 Delivery of Loss Prevention Training on SCO

As can be seen, when SCO supervisory staff receive training on loss prevention issues, they are largely positive – 92% considered it to be very well or quite well covered, with just 8% having a negative view.

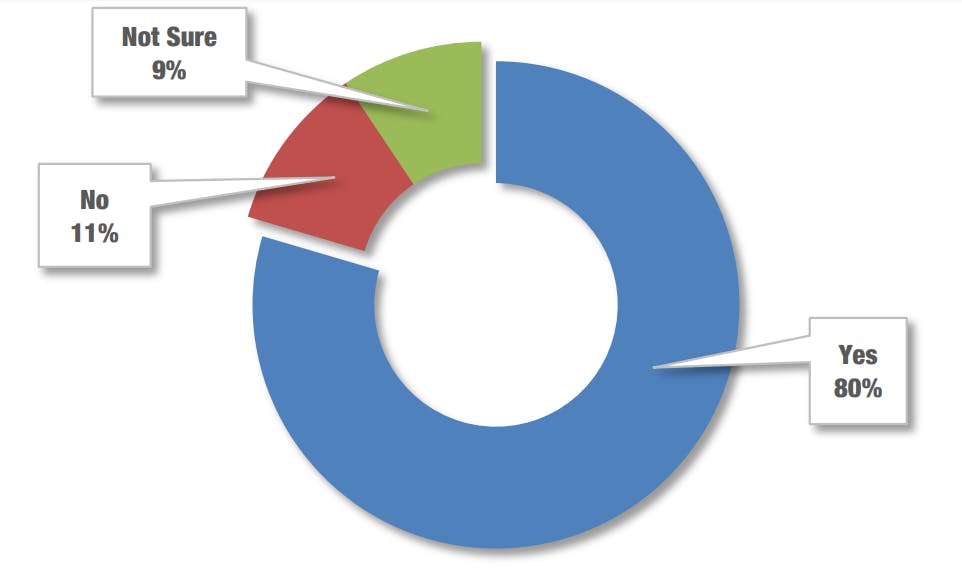

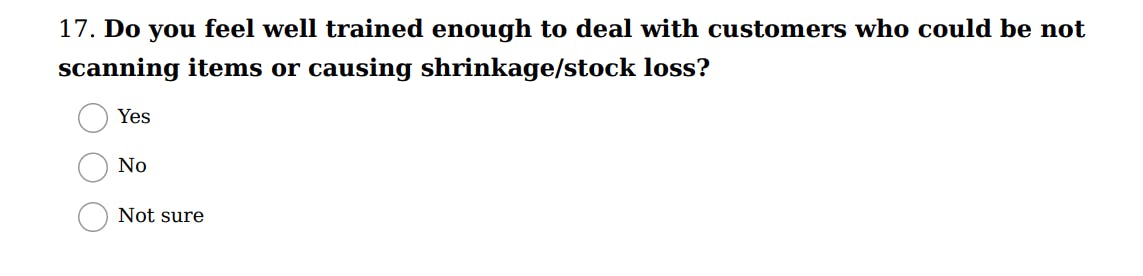

Preparedness to Deal with Non-scanning Abuse

Another way to assess this issue was to ask respondents whether they felt adequately prepared to deal with non-scanning misuse (Figure 15).

Figure 15 Feel Prepared to Deal with Non-scanning Misuse

Overall, the response was very positive – over three-quarters (80%) were of the view that they were prepared to deal with non-scanning misuse, with only a small minority who did not think this was the case (11%). In addition, there was also one in eleven respondents (9%) who were unsure as to whether they were prepared or not.

There were differences in responses, however, based upon the training received – those who had longer periods of training (more than an hour or so) felt more prepared to deal with misuse22, and more specifically, those who had received LP training were far more likely to say that they felt prepared to deal with non-scanning misuse – 86% said yes, compared with 66% who had not received LP training23. Once again, training seems to be an important factor in preparing staff to deal with the vagaries of working in the SCO environment.

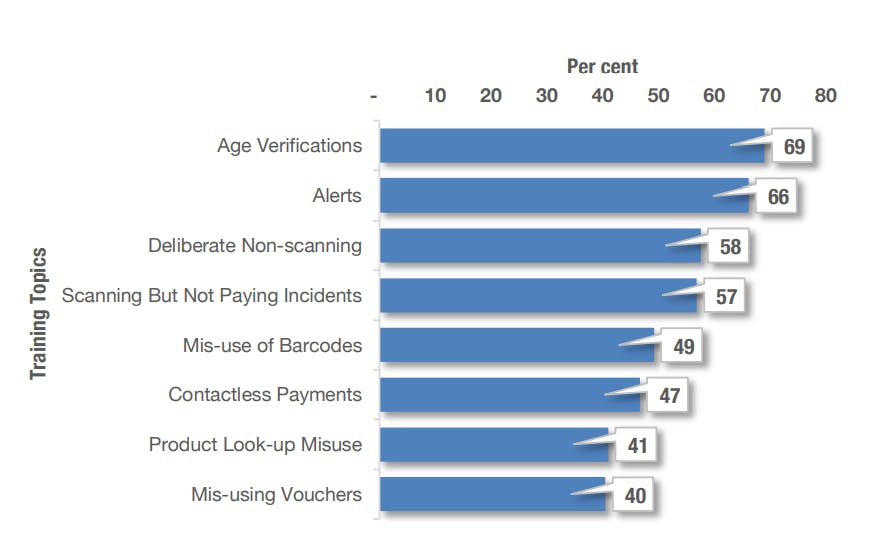

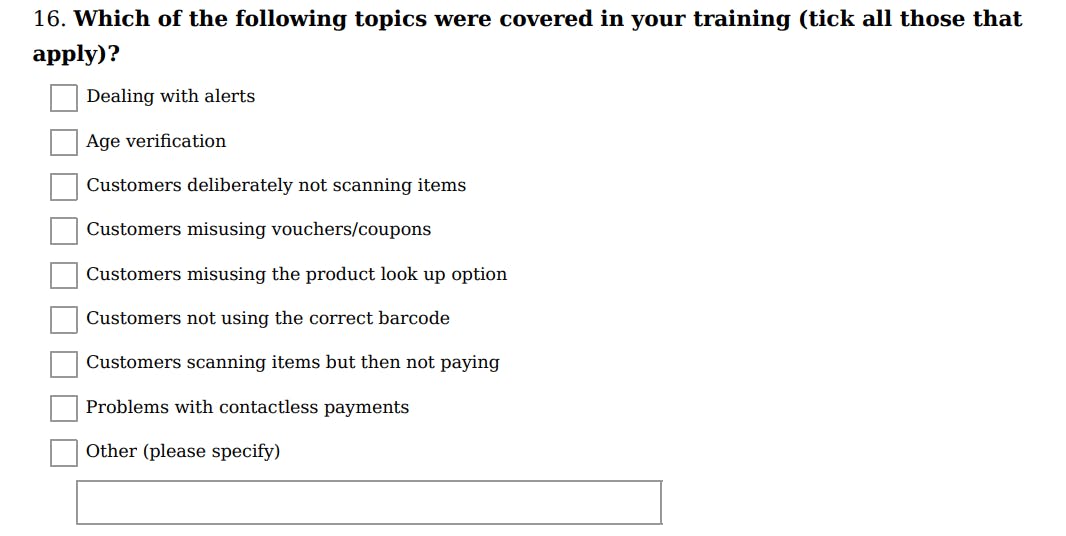

Topics Covered in Training

The survey went on to ask respondents that had received any form of training about the range of SCOrelated topics that were covered (Figure 16). Respondents were asked to comment about whether eight topics had been covered or not in their training; three related to generalised SCO issues (age verification checks, dealing with contactless payments, and responding to alerts), while the remaining five were more focussed upon malicious forms of user behaviour (scanning but not paying, deliberately non scanning items, mis-using barcodes and vouchers, and product lookup misuse).

Figure 16 Topics Covered in SCO Training

The topic most likely to be covered was dealing with age verification alerts – just over two-thirds said that this issue had been covered (69%), followed by dealing with alerts in general (66%). These were then followed by two key SCO misuse issues: users deliberately not scanning items, and walking away from SCO after scanning items but not paying for them (58%). Topics that were much less likely to be included were the misuse of vouchers (40%), product look up misuse (41%) and issues relating to contactless payments (47%).

The survey found that the number of topics covered is associated with the length of the course – the longer the course, the more topics were covered. The shortest period of training (just an hour or so) typically covered 30% fewer topics than the longest training period (2 days or more).

It was also found that respondents who said they had covered more topics were more likely to consider their overall training very useful or useful24. It was also the case that those that covered more topics were also more likely to think that they were better prepared to deal with non-scanning misuse25.

Finally, those that received a greater number of topics as part of their training were also more likely to feel better able to cope with the number of SCO machines allocated for supervision26.

Improving SCO Training

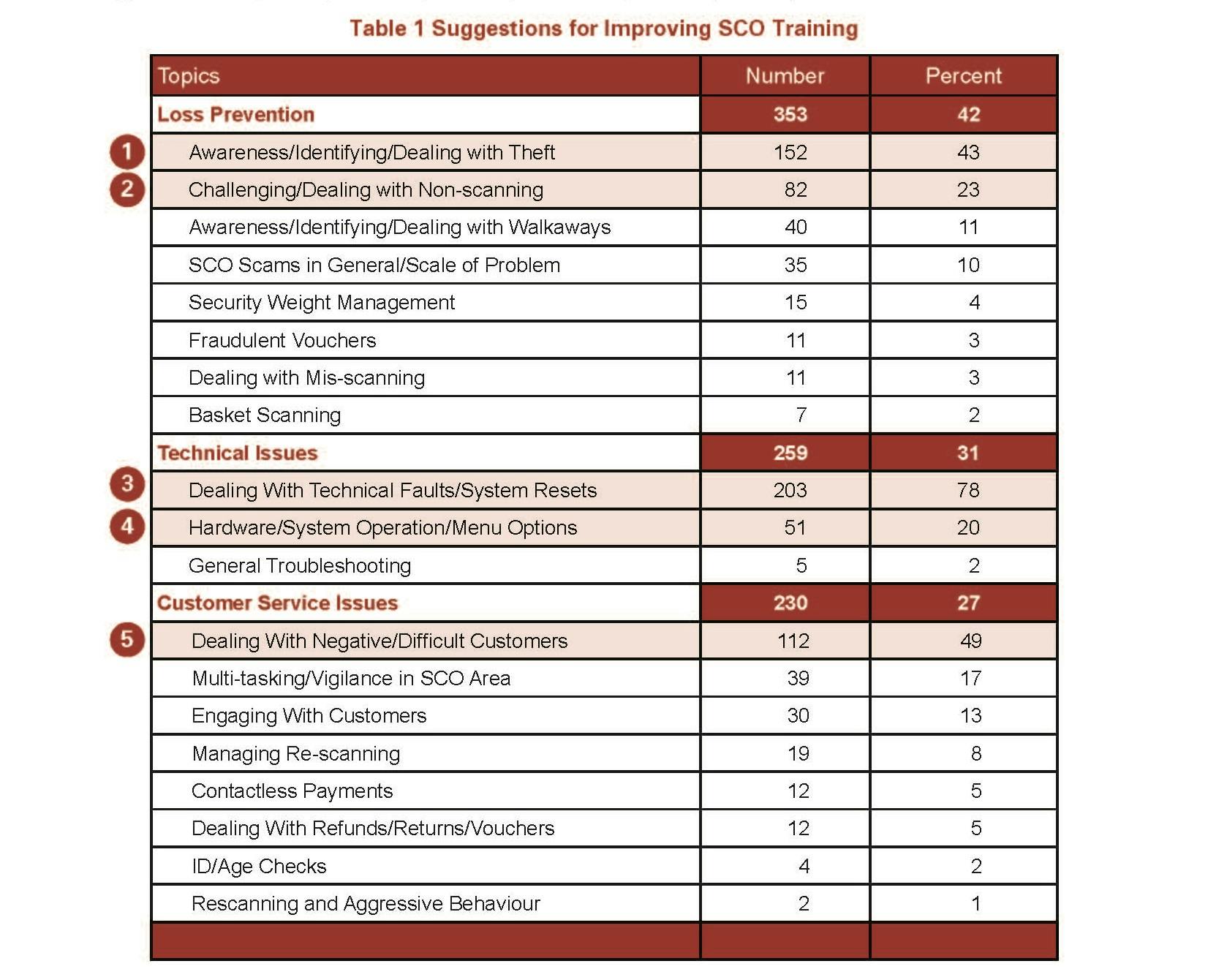

The final part of this section looks at the suggestions provided by respondents for how they thought their training could be improved, based upon an open-ended question (Table 1).

Table 1 Suggestions for Improving SCO Training

The analysis identified three broad areas of interest: those relating to loss prevention, which accounted for 42% of all the comments; issues focussed upon technical aspects of the SCO operation (31%); and those relating to customer service issues (27%).

Loss Prevention Issues: the most common topic that respondents thought would improve their SCO training programme was greater awareness of, and capabilities to deal with, theft in general. For instance:

When dealing with a guest who is skip scanning, or potentially attempting theft, training should cover things as to what to say, how to go about the situation, also how to deal with the guest if they become defensive and arguing.

This was closely followed by three related areas: better training on how to challenge and deal with incidents of non-scanning, and walkaways, and more awareness of generalised SCO scams. Taken together, these four issues accounted for 88% of all the suggestions focussed upon loss prevention.

Technical Issues: respondents were very clear that the area where they thought their training could be improved was better preparing them to deal with technical faults and system resets (78% of all responses in this area). A wide range of specific issues were raised including: coin blockages; system resets; fault diagnostics; freezing screens; jammed till rolls; and general preparedness for when something goes wrong with the technology: ‘More training given to staff on how to deal with the machines if they stop working’. This was followed by improved training on how the SCO technology worked in general (20%): ‘I think that we should be taught more about all the different functions that you can do on the self-checkouts’.

Customer Service Issues: dealing with negative or difficult customers was the most cited issue within this category – nearly one-half of all comments related to this (49%), although they were often positioned within the context of other issues. For instance, problems with faulty SCO machines and incidents of attempted customer misuse (such as non-scanning) were often triggers for this type of behaviour. For example, one respondent said:

Yes, how to deal with customers who swear and talk down to you; this happens every single shift I work on! A lot of customers have no patience and because I’m always on my own they get mad and start shouting and swearing.

Another highlighted this issue in relation to SCO misuse by customers: ‘Maybe ways to deal with difficult customers especially if they’ve been caught not scanning items’.

Three other topics were also particularly highlighted as areas to be better covered by training: how SCO staff can be better vigilant in their work environment, how they can more effectively multi-task in this space, and how they can more effectively engage with SCO customers: ‘More training on how to approach without accusing’; ‘More focused on the interaction and acknowledging all guests’.

The Self-checkout Operating Experience

As mentioned earlier, those operating daily in a SCO environment can offer detailed and illuminating insights into what is happening in these spaces, something which can be extremely difficult to capture in other ways. This section of the reports summaries how respondents view several inter-related issues:

- Perceptions of the extent of misuse occurring at SCO.

- Frequency of SCO alerts and misuse issues.

- Perceptions of the potential effectiveness of a range of possible interventions.

- Levels of violence and verbal abuse occurring in this space.

- How the SCO operating environment could be improved.

Rate of Malicious SCO Misuse

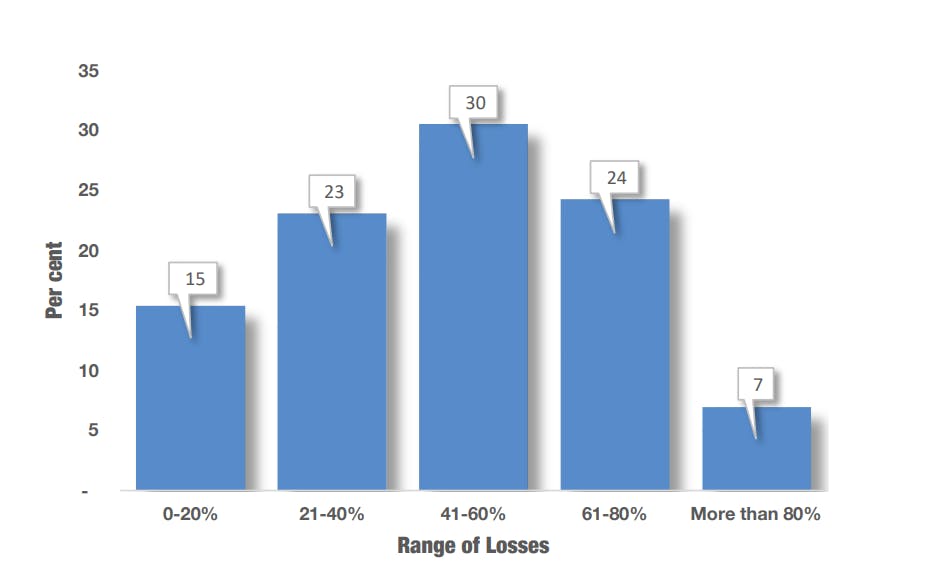

Various surveys and studies have offered estimates of the extent to which SCO systems generate losses for the retailers operating these systems27. One of the key questions is the extent to which the losses emanating from SCO are due to non-malicious acts by users (accidental errors) compared with malicious (criminal) actions – users purposefully misusing systems for their own advantage. The survey asked respondents to estimate what percentage of losses that occur at SCO they thought were due to deliberate misuse by customers (Figure 17).

Figure 17 Percentage of SCO Loss Due to Deliberate Misuse

Using a sliding scale from 0% to 100%, respondents were able to select any value they liked. As can be seen, the largest proportion of responses were found in the 41%-60% range, with one-quarter thinking it was slightly lower (21%-40% of all losses) and one-quarter thinking it was slightly higher (61%-80% of all losses). Taken together, the overall average across all respondents was 51% – one-half of all SCO-related losses were considered due to malicious behaviour by customers. This is not too dissimilar to findings from earlier ECR Retail Loss research based upon a global survey of loss prevention representatives. They thought that on average 43% of Fixed SCO losses were malicious in nature28.

In the current survey there was some variation in attitudes across types of respondents – those that have worked longer and more frequently on SCO typically thought that the rate of loss due to deliberate misuse is on average, slightly higher – 53%. There was also a weak correlation between the number of SCO machines a respondent had to supervise and the rate of perceived loss due to deliberate misuse – those with higher numbers of SCO machines thought losses were higher29. While these numbers are only based upon the perceptions of those completing the survey, it is interesting to note that those who have worked the longest on SCO and have higher numbers of machines to supervise believe losses are higher than the overall average.

Frequency of SCO Alerts and Problems

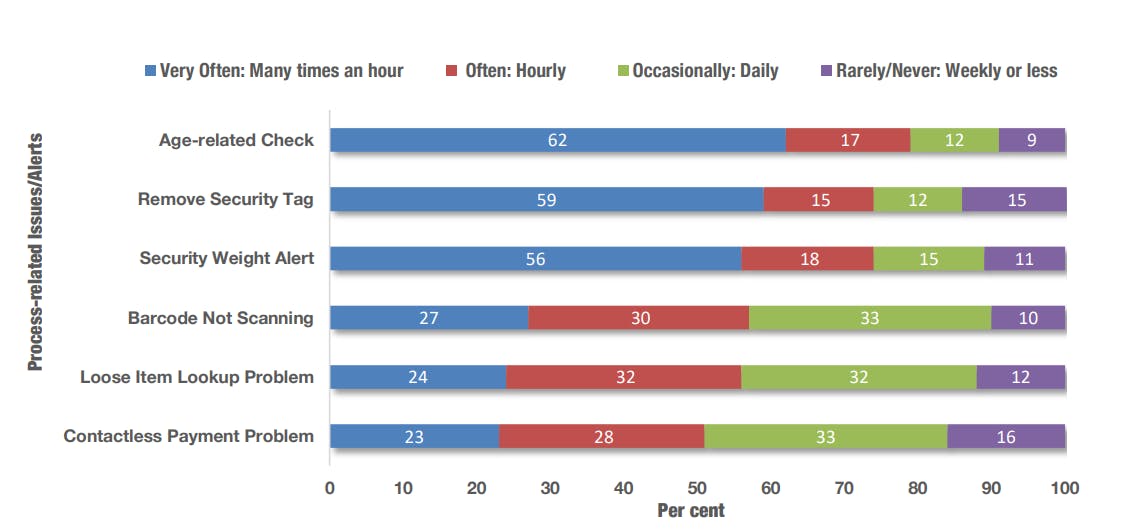

A fundamental part of managing the Fixed SCO operating environment is dealing with a range of systemtriggered alerts and user-generated problems. Some of these are a necessary part of the legal requirements of the retail environment (such as verifying the age of those wishing to purchase alcohol or other restricted items), others are an inevitable consequence of the loss prevention strategy in place (removing/deactivating product security tags), while some are a result of the user/system interaction not functioning properly (barcodes not scanning, customers not able to find items in product lookup menus, problems relating to contactless payments, and issues with the security weight checking system). Figure 18 provides a summary of the frequency with which SCO supervisors believe these various types of issues and alerts occur, ranging from many times an hour through to weekly or less. It should be noted that respondents were also able to select ‘not applicable’ where an option was not present in their working environment. For the sake of brevity, these responses have been excluded.

Figure 18 Frequency of Process-related Issues/Alerts

While it is not surprising that both age-related checks and removing security tags are issues regarded as happening the most frequently, with the former being seen as happening many times an hour by 62% of respondents, and the latter by 59%, what is more of an issue is the extent to which the remaining problems occur on such a regular basis.

Firstly, the problem of security weight alerts – the system designed to trigger an alert when a product is placed in the packing area that has not seemingly been registered on the EPOS system. In terms of whether this is a process or misuse issue, it is undoubtedly a grey area – instances can occur when a customer has legitimately scanned an item, but the weight-based system does not correctly identify it when placed in the packing area. Indeed, in the early days of SCO being rolled out more widely, the automated system refrain: ‘unexpected item in the bagging area’ became a much-derided part of the self-checkout customer experience30. While it is not clear from this survey the extent to which these alerts are genuine or not, and for many retailers operating SCO it remains a fundamental part of their loss prevention strategy, this type of alert undoubtedly generates a considerable number of interventions for SCO supervisors, with 56% saying they happen many times an hour.

It is also interesting to note the frequency with which the remaining problems are also seen to occur. Over 50% of all respondents think that they must deal with issues relating to problems associated with loose item look up, barcodes not scanning properly and contactless payment issues on an hourly basis or more. Indeed, for all three problems, almost one-quarter of respondents believe they happen many times an hour in their operating environment.

If the issue of security weight alerts is put to one side, these three remaining factors, none of which are an inevitable consequence of legislation nor company policy, are clearly, and unnecessarily, occupying both SCO supervisor time and likely frustrating the shopper journey on a routine basis. All have the potential to be reduced in frequency through better design, be it through system and/or process improvements. For instance, the design and positioning of barcodes on products most frequently causing scanning problems should be reassessed with manufacturers – how can they be improved to make them more ‘SCO compatible’?

Frequency of SCO Misuse by Customers

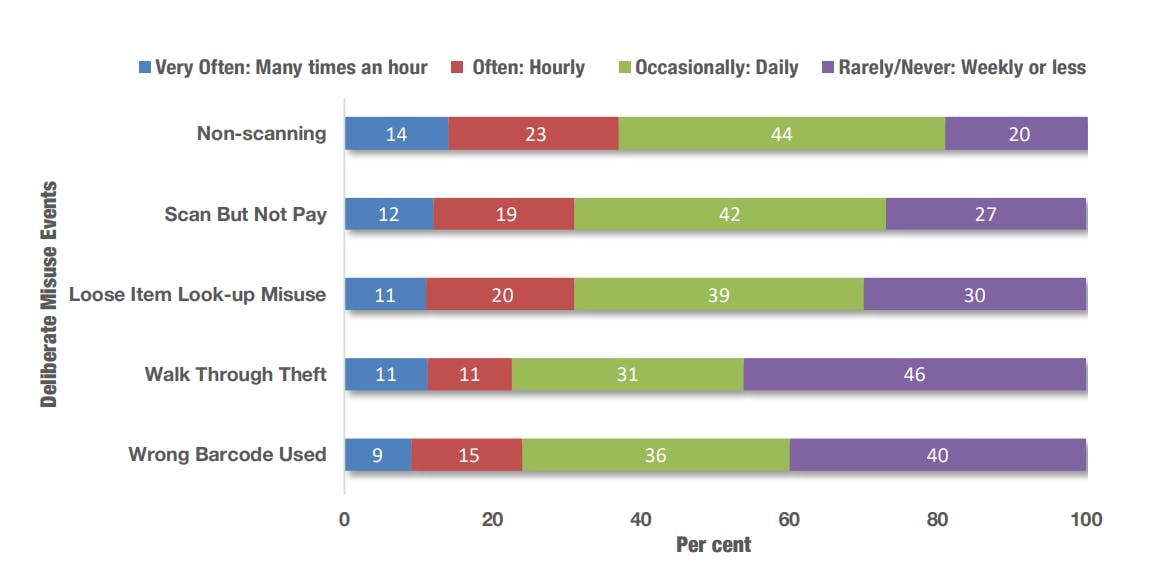

Respondents were then asked to estimate the frequency with which a range of events associated with the misuse of SCO systems were occurring (Figure 19) ranging from many times an hour through to weekly or less.

Figure 19 Frequency of Deliberate Misuse Events

Previous research has identified the three ways in which SCO systems are typically misused: users deliberately not scanning items, users misrepresenting one product for another (usually via the product look-up facility); and users scanning items but then walking away without paying. What is interesting is that for each type, about one-third of respondents believe they are happening on an hourly basis or more frequently. More broadly, between 69% and 79% believe these types of events are happening daily in their SCO environment. All three types of misuse appear to be a significant and frequent issue as viewed by SCO supervisors. It is also interesting to note the rank order of frequency – non-scanning followed by customers scanning but not paying for their goods, and loose item look-up misuse.

The remaining two types of misuse – deliberately using the wrong barcode and using the SCO area as means to exit the store with stolen goods are seen to happen less frequently although 1 in 10 respondents do believe that they happen many times an hour where they work.

Violence and Verbal Abuse at SCO

As detailed earlier, SCO supervisors routinely both witness and have responsibility for responding to a wide range of issues, alerts and problems that can occur in and around the SCO environment. This includes nonmalicious problems that may be due to SCO equipment not working properly but also malicious behaviours such as SCO users deliberately trying to steal products through non-scanning, mis-scanning, and walking away without paying. This can lead to interactions between customers and SCO supervisors that can generate violence and verbal abuse. The survey was therefore interested in understanding from respondents how frequently they thought these types of incidents occurred in their working environment (Figure 20).

Figure 20 Frequency of Violence and Verbal Abuse at SCO

Over 4,500 respondents answered this question and of those, one-third (32%) stated that incidents of violence and verbal abuse occurred very often or often (at least weekly). In addition, a further one-quarter (24%) were of the view that they happened monthly (Occasionally). More reassuringly, one-third (33%) felt that these types of incidents were relatively rare, happening only a few times a year or less. Finally, 1 in 9 (11%) respondents stated that it never happened in their working environment.

There were several differences within the sample. Firstly, there was a small but significant difference between respondents who had and had not received training (or were not sure they had) and the frequency with which they stated violence and verbal abuse occurred. Those that had not received training were more likely to suggest it happened more often (very often/often: received training 31%, not received training/unsure 37%)31. In addition, those staff that worked longer shifts (more than 1-2 hours) were far more likely to state that they had experienced violence and verbal abuse very often/often (42% compared with 24%)32. It was also found that those staff that had been with the company longer and had worked on SCO longer, were more likely to say that violence was occurring very often/often33.

There was also a correlation between the amount of time staff work on SCO and the frequency with which violence and verbal abuse occurred – respondents who worked on SCO daily (44%) compared with those who worked less frequently (15%)34. The survey also found that there was a correlation between how frequently violent and verbal abuse incidents were considered to happen and the number of SCO machines that respondents said they had to supervise35. Those with more SCO machines were more likely to say that incidents happened more often. While correlation does not equal causation, it would seem likely that as staff members have to deal with a greater number of machines and associated alerts and problems, levels of customer frustration are also likely to grow, which in turn could spill over into violence and verbal abuse.

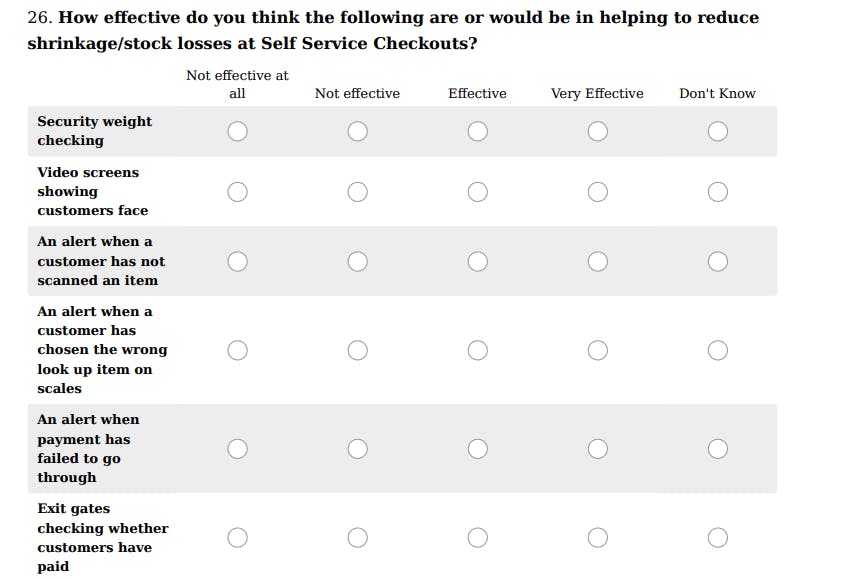

Effectiveness of Interventions:

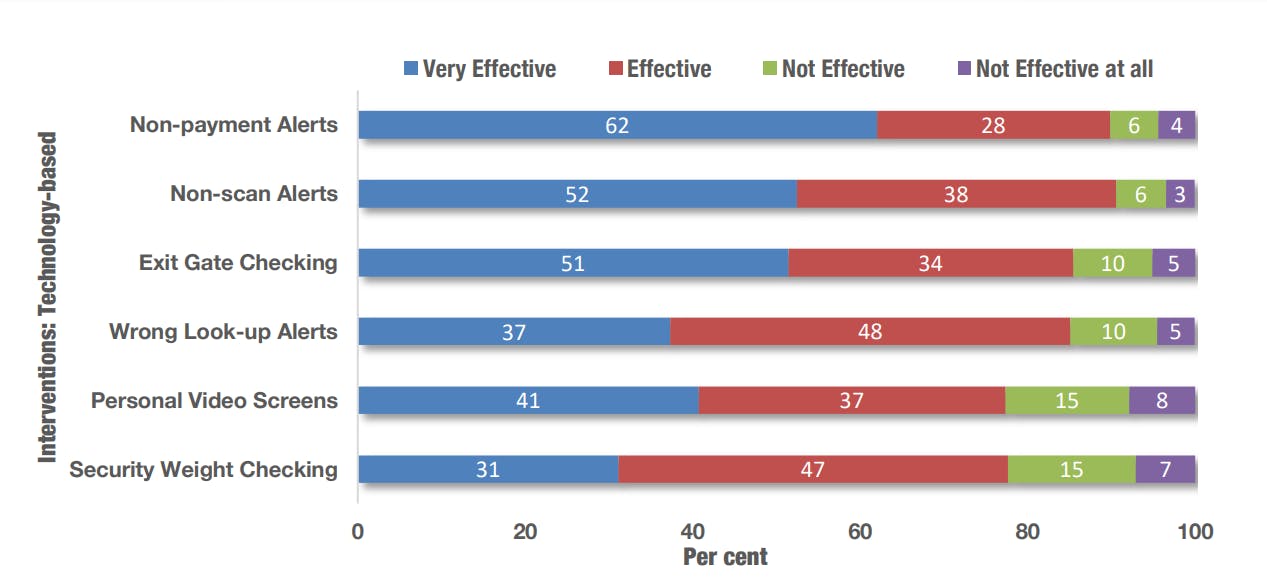

Technologies As retailers have become more aware of the scale and extent of the losses associated with their various SCO systems, they have begun to invest in a range of interventions designed to try and address this issue. While respondents to this survey did not have access to any form of verifiable data to inform their thoughts around how effective or not different types of intervention might be (beyond what they had experience of in their store36), their thoughts and perceptions are useful in terms of an indirect expression of their concerns about types of SCO problems and their prioritisation of them. Detailed below in Figure 21 are their views on a range of technology-based interventions.

Figure 21 Perceived Effectiveness of Technology-based Interventions

The intervention that was regarded as likely to be the most effective was non-payment alerts – 90% thought that this would be effective or very effective. This relates to a range of concerns about contactless payments and the challenges that SCO staff face in ensuring that they are undertaken correctly by customers. Because of the nature of the technology, it is relatively easy for customers to either not realise that payment has not occurred, or make it look as though they have paid when in fact they have not. Either way, respondents were clearly of the view that this was a pressing concern and that some form of alerting system would be highly beneficial37.

The next three interventions that were highly rated aim to address the three forms of SCO abuse that are regarded as the most common – non-scanning, walkaways, and mis-scanning. Again, staff believed that any form of alerting/intervention aimed at giving them notice that these types of misuse were occurring were considered effective.

In relative terms, the two interventions considered the ‘least’ effective were personal video screens, where the face of the user is displayed, and security weight checking. The latter’s relatively lowly rating may be due to real world experience of having to deal with large numbers of false alarms generated by it, while the former may be viewed as a rather passive intervention unlikely to deter would-be offenders.

Overall, the six proposed interventions scored relatively highly in terms of perceived effectiveness (77% or higher regarded as effective or very effect), which points to a generalised desire by SCO staff to have further help to deal with loss generating problems in their work environment.

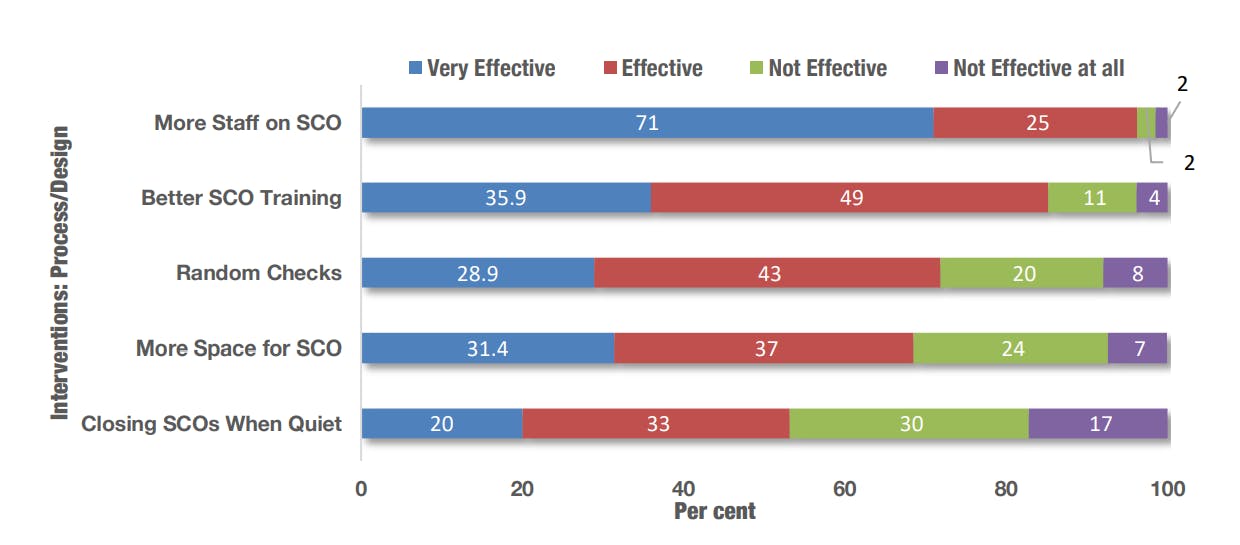

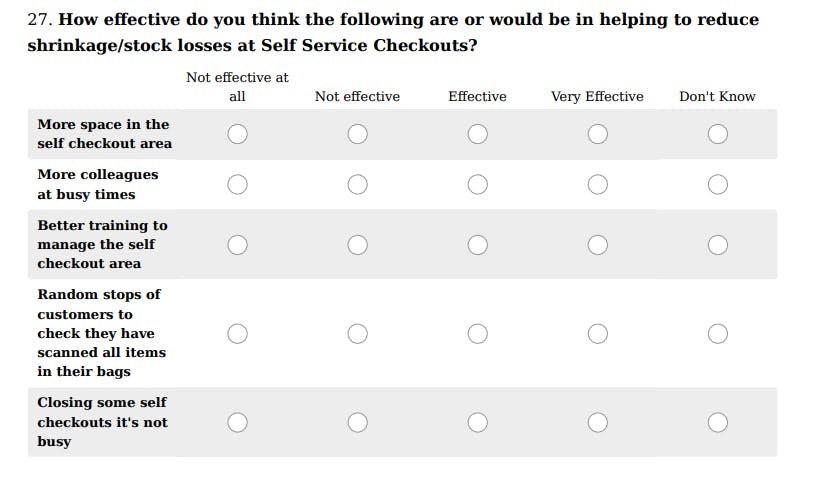

Effectiveness of Interventions: Processes and Practices

Beyond a range of technology-based interventions, respondents were also asked to consider several process/ design interventions that might help them to deal with SCO-related losses (Figure 22).

Figure 22 Perceived Effectiveness of Process/Design-based Interventions

Respondents were almost unanimous in their view that having additional staff to supervise the SCO area would be an effective or very effective intervention (96%). The issue of staffing levels will be discussed later in this report when respondents offer their suggestions for how their SCO programme could be improved, and it is perhaps not surprising that they would like more help (who wouldn’t?!), but it is clearly something that respondents consider to be an effective way to reduce SCO-related losses. Ranked second was another ‘people’ issue, the importance of better training – again a ringing endorsement for this form of intervention.

In third place was the use of random checks to both ensure customers had scanned and paid for all their products and to offer a form of deterrence against future offending. While some retailers have introduced this type of checking in Fixed SCO areas, it is a practice that is relatively uncommon and, in those markets where it has not been done before, may cause unacceptable levels of customer friction if not executed very well. It also clearly has implications for the SCO labour model as it would add a further task to those already required.

Providing more space in the SCO area was ranked fourth and finally, the process of closing some SCOs in quiet periods was the intervention considered to be the least effective (although a majority did still think it would be helpful).

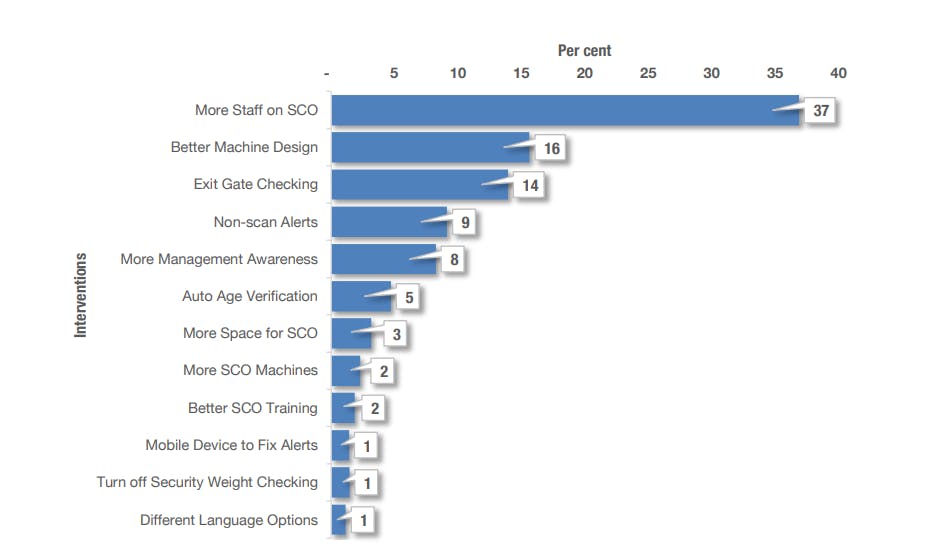

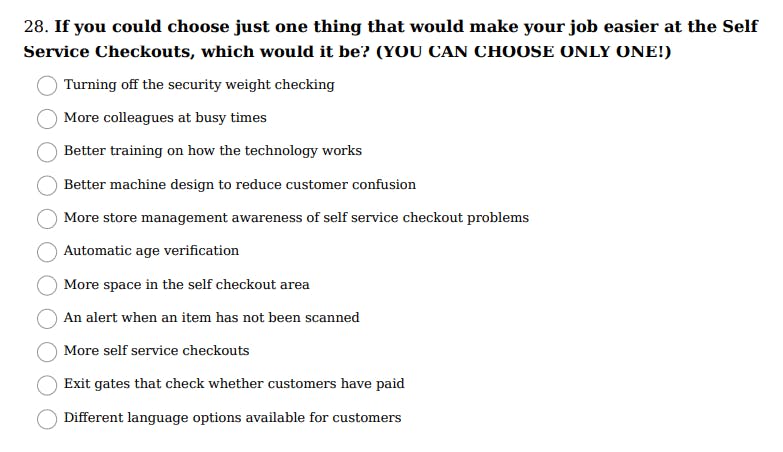

Most Effective Intervention

To try and generate a better idea of which intervention would be considered most likely to be helpful, respondents were asked to choose only one from a list of possible options (Figure 23).

Figure 23 Most Effective Intervention

Of the more than 4,500 responses to this question, by far and away the most popular response was more staff in the SCO area – 37% chose this option. This was followed by 16% who thought that better designed SCO machines would be the most effective and 14% who would like to see exit gate checking to help deal with SCO-related losses. These three options accounted for two-thirds of all the responses (66%) – have more staff to supervise the area, make sure the machines are user-friendly and reliable, and ensure that misusers cannot easily leave the SCO space without passing some form of check.

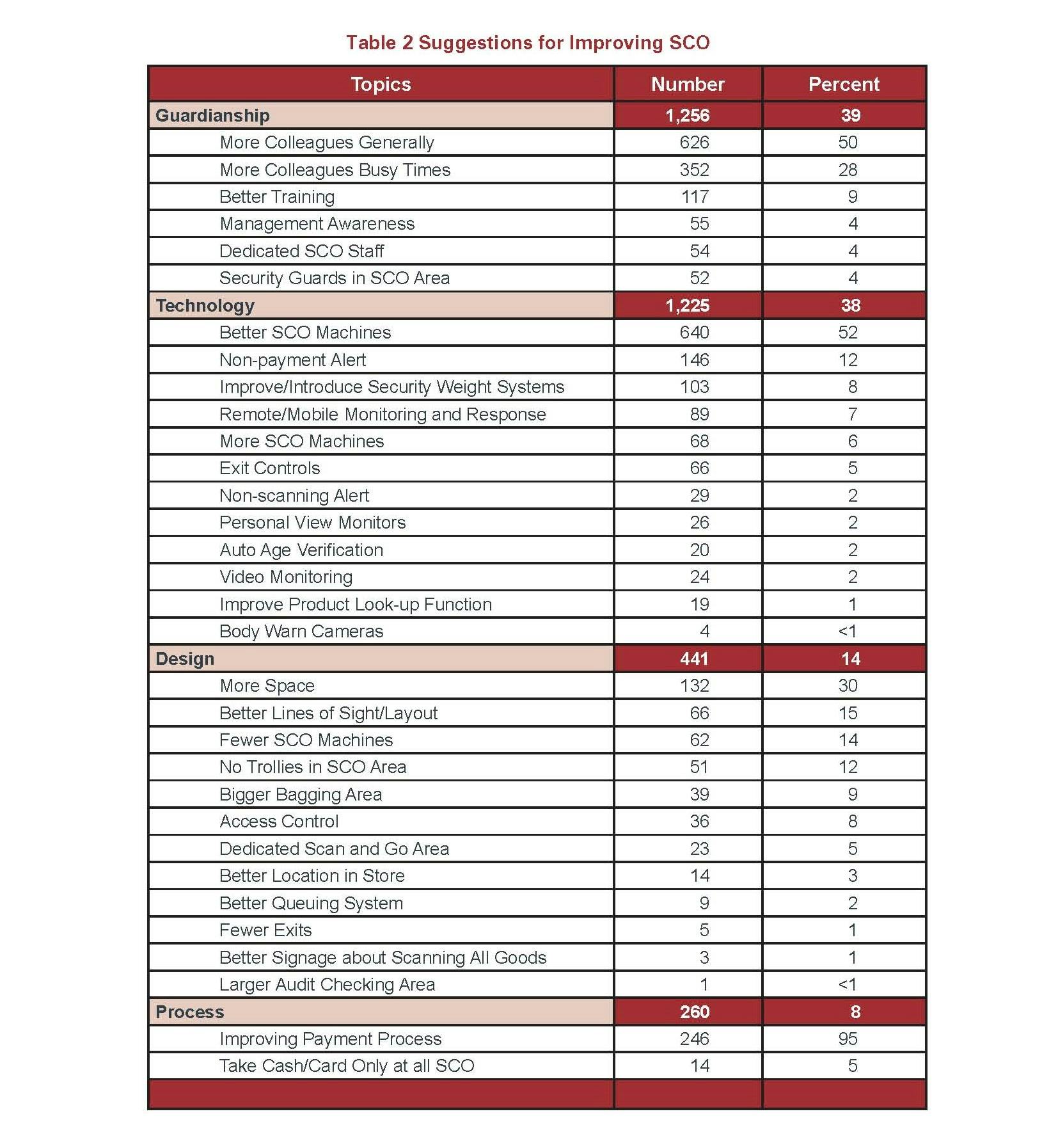

Improving the Self-checkout Working Environment

The final question presented to respondents asked them to make suggestions as to how their SCO working environment could be improved. It was an open question and solicited over 3,000 responses which have been coded into four key areas: Guardianship, Technology, Design, and Process (Table 2).

Table 2 Suggestions for Improving SCO

Across the four categories, most responses related to ideas relating to guardianship (39%) although technologyfocused interventions were a close second (38%). Issues relating to design were ranked third (14%) and process approaches were a distant fourth (8%).

Guardianship

Responses in this section were dominated by two inter-related ideas – generally more colleagues working in the SCO area, and more colleagues at busy times. Together they accounted for 78% of all the Guardianshipfocused responses. Here are just some examples of comments made by respondents:

We need more staff; the self-checkout [area] is unmanageable with just one attendant, especially when all registers are in use.

[We need] more people when it’s busy – I’m currently running [Fixed] SCO and Scan and Go by myself, it’s ridiculous.

Feel that extra help at busy times would go a long way to help me feel that people are not stealing in self check. I feel that as soon as I turn my back to help customers others might be putting things in their bags

This issue has been highlighted elsewhere in this report – respondents believing that they cannot cope well with the demands of working in the SCO area, particularly if they are to provide a credible method of deterring and detecting errors and misuse. Moreover, if the further two categories of Dedicated SCO Staff and Security Guards in the SCO area are included, then nearly 9 in 10 responses focussed upon the importance of having more staff in the SCO area.

Two other issues were raised by respondents although to a much lesser degree. The first related to the importance of having better training of staff to help them perform their duties (9%), and improving management awareness of issues relating to the SCO environment; ‘More thorough training to handle any issues that arise’; ‘Better training for staff who are new to the department; not just a few hours but proper training’; ‘All management to be fully trained on the [SCO] department and spend time working on it to fully understand issues that may occur’.

While the issue of training has been covered earlier in this report, the latter raises an important point about respondents’ sense that those tasked with managing the store environment are not fully cognisant with the challenges they face. Certainly, one of the suggestions made by groups such as ECR Retail Loss is that senior leaders would gain powerful insights were they to carry out the role of a SCO supervisor for at least a few hours, and this was something suggested by many respondents to this survey. For instance: ‘All management to know how to use the self-service tills, and actually work on there at least one day a week (preferably the weekend as its busier) to see what actually goes on’; ‘Head office to work a shift on self-service to actually understand and see what happens’; ‘Get the store manager to work a full shift on them [SCO] at busy times then they may better understand how stressful it can be’.

Technology

Respondents offered up a range of technology-based interventions and ideas for how the SCO area could be improved and two were particularly popular. The first was a generalised request for better SCO machines that were less likely to breakdown and have faults, but also were quicker and had a user interface that was less likely to lead to customer confusion and frustration (52%). Respondents raised a wide range of issues, including:

Update to the machines because they easily break down and cause customer confusion and frustration, especially when during a large shop and it breaks down mid payment.

Software needs to be improved; SCO get issues every day and we are not be able to fix it without calling technical support.

We need new ones! Ours are terrible.

The second issue was the use of some form of non-payment alerting system. As discussed elsewhere, respondents are particularly concerned about problems generated by contactless payment systems where it is felt that it is very easy for customers to walk away under the impression that they have paid when in fact they have not (12%).

The payments are hit and miss … a lot of walk offs because people believe they have paid but they haven’t.

[We need a] immediate alert that a customer hasn’t paid rather than a message a few minutes after they’ve left the checkout asking if they want to continue their purchase.

I think having something in place to let customers know their card hasn’t gone through when they’ve scanned it. Too many people just tap their card and think it’s gone through.

Respondents also mentioned a range of other ideas, including introducing or improving security weight checking systems (8%), the capacity to remotely monitor and respond to alerts (7%) and exit controls (5%).

Design

Several inter-related design-focussed ideas were suggested by respondents. The most common response was a desire for more space in the SCO area (30%) followed by having a better design of the space, including improved lines of sight of SCO machines and users (15%):

More space between the self-checkouts – allow customers to flow better and give better colleague visibility to see what customers are up to.

More space as it’s so crammed you can’t see what people are doing half the time.

Other suggestions included having fewer SCO machines to supervise (14%), not allowing trollies/carts in the area (12%), bigger bagging areas (9%), and improved access control/better queuing system (10%).

Some respondents working in retailers where there was a mix of Fixed SCO and Scan and Go systems in operation thought that these areas should be kept separated (5%), often because it was difficult for staff engaged in Scan and Go-related auditing duties to respond in a timely fashion to those having problems in the Fixed SCO area.

Process

The final main area of suggestions was those related to improving SCO-related processes. Only two suggestions were readily identifiable from respondent’s comments. The first and most common related to the payment process (95%), not least issues around whether customers should and could be able to tender cash as well as card payments:

Make all checkouts able to take cash or card. Customers have to wait too long for a cash self-serve to be free. We often have queues and two checkouts not being used because they can’t pay cash.

In addition, several retailers taking part in this survey had company-specific payment peculiarities that were viewed by many respondents as generating unnecessary levels of customer frustration and delay. For example: ‘I would say about 70-80% of my job at self-checkout is telling people to hit the [xxx] button after they pay on the pin pad; most self-checkouts at other stores don‘t require that extra step’.

SUMMARY

New Insights on the World of Self-checkout

Much of the previous research on retail SCO has relied upon, and been derived from, either company data, such as rates of loss, and/or the views of those at an organisational level who have overall responsibility for its design, implementation, and review38. While both offer key insights into the operation of SCO, what has largely been missing are the views and experiences of those directly tasked with managing and controlling it in retail stores – those working on the SCO ‘front line’. This current study, therefore, plugs this gap, summarising the views and experiences of more than 6,000 SCO supervisors operating in Europe, the US and Australia.

The Value of Guardianship

It is very easy to be beguiled by the promise of technologies, after all, we are living through a period where the appliance of science has fundamentally transformed many aspects of our daily lives, not least health, communication, entertainment, and of course shopping39. Developments such as E-commerce, autonomous stores, and the growing use of various types of self-scan and checkout systems are testament to this change. But, at its very core, retailing is still very much a ‘people’ business – staff employed to deliver an attractive, sustainable, and profitable enterprise. Without well trained, motivated, watchful, and rewarded staff, most retail businesses will ultimately fail40.

When it comes to the delivery and control of SCO systems in a retail environment, this study has highlighted the important role guardianship plays. Yes, some retailers have developed store concepts where there are no visible staff, but they are few and far between, occupying a tiny slither of the retail market41. For the most part, retailers deploying SCO systems rely upon staff to make them a credible proposition, although the extent to which this is fully understood seems to be more questionable.

Indeed, one of the early selling points of SCO was the way in which it could enable retailers to markedly reduce their labour costs – instead of one member of staff only being able to checkout one customer at a time, now, depending upon the ratio of SCO machines to staff, the same member of staff can oversee 4, 6, 8, or maybe more customers checking out at the same time. Given that labour costs are the second largest line of expenditure for a retailer, this is clearly an attractive proposition, especially when early reviews of SCO suggested that associated losses were minimal42. In many retailers, this created a ‘minimal possible’ staffing operating model – what is the least amount of labour we can deploy to make SCO ‘deliverable’?