Total Retail Loss 2.0

From Theory to Practice

Table of Contents:

- Abstract

- Foreword

- Executive Summary

- Background and Context

- Reviewing Retail Awareness of Total Retail Loss

- Understanding the Utilization of Total Retail Loss

- Barriers, Concerns and Challenges to Adopting Total Retail Loss

- An Updated Total Retail Loss Typology

- Getting Started on a Total Retail Loss Journey

- Conclusions

Languages :

The original research outlining the Total Retail Loss concept was first published in 2016, focussed upon understanding how the retail industry understood the nature and extent of all the potential types of losses they experience, as well as publishing a definition of ‘loss’ and associated typology (made up of 33 categories of loss).

It was based upon a detailed literature review together with an online survey of retailers and 100 interviews with senior retail executives in the US.

In 2019, a new report on TRL was published, providing not only a revised Typology, now containing 42 categories of loss, but also a comprehensive review based upon an online survey of retailers based in Europe and the US, together with 17 in-depth interviews with loss prevention practitioners.

The new study provides details on the extent of awareness of the TRL concept, the degree to which it has been adopted, the retail rationale for engaging with TRL, and how it should evolve to meet the changing retail context. It concludes with a series of factors prospective adopters might want to consider, which includes: getting the C-suite onboard; developing a clear business case; adopting an incrementalistic approach; identifying quick wins first; and developing a clear approach as to how TRL will be managed in the business.

It concludes by hoping that both this new research and the original work developing the TRL concept will enable the retail industry to strive towards a more coherent, integrated and progressive approach to the management of losses and ultimately the protection of profits.

This report was commissioned by the Retail Industry Leaders Association, with the support from the ECR Retail Loss Group. The report is presented here with their permission.

About the Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA)

RILA is the US trade association for leading retailers. RILA convenes decision-makers, advocates for the industry, and promotes operational excellence and innovation. Their aim is to elevate a dynamic industry by transforming the environment in which retailers operate.

RILA members include more than 200 retailers, product manufacturers, and service suppliers, which together account for more than $1.5 trillion in annual sales, millions of American jobs, and more than 100,000 stores, manufacturing facilities, and distribution centers domestically and abroad.

For further information: www.rila.org

Abstract

The original research outlining the Total Retail Loss concept was first published in 2016, focussed upon understanding how the retail industry understood the nature and extent of all the potential types of losses they experience, as well as publishing a definition of ‘loss’ and associated typology (made up of 33 categories of loss).

It was based upon a detailed literature review together with an online survey of retailers and 100 interviews with senior retail executives in the US.

In 2019, a new report on TRL was published, providing not only a revised Typology, now containing 42 categories of loss, but also a comprehensive review based upon an online survey of retailers based in Europe and the US, together with 17 in-depth interviews with loss prevention practitioners.

The new study provides details on the extent of awareness of the TRL concept, the degree to which it has been adopted, the retail rationale for engaging with TRL, and how it should evolve to meet the changing retail context. It concludes with a series of factors prospective adopters might want to consider, which includes: getting the C-suite onboard; developing a clear business case; adopting an incrementalistic approach; identifying quick wins first; and developing a clear approach as to how TRL will be managed in the business.

It concludes by hoping that both this new research and the original work developing the TRL concept will enable the retail industry to strive towards a more coherent, integrated and progressive approach to the management of losses and ultimately the protection of profits.

This report was commissioned by the Retail Industry Leaders Association, with the support from the ECR Retail Loss Group. The report is presented here with their permission.

About the Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA)

RILA is the US trade association for leading retailers. RILA convenes decision-makers, advocates for the industry, and promotes operational excellence and innovation. Their aim is to elevate a dynamic industry by transforming the environment in which retailers operate.

RILA members include more than 200 retailers, product manufacturers, and service suppliers, which together account for more than $1.5 trillion in annual sales, millions of American jobs, and more than 100,000 stores, manufacturing facilities, and distribution centers domestically and abroad.

For further information: www.rila.org

Foreword

Total Retail Loss 2.0 builds on the ground-breaking research commissioned three years ago by the RILA Asset Protection Leaders Council in partnership with Professor Adrian Beck from the University of Leicester in the UK.

The results are compelling: Retailers around the world have embraced and are benefitting from the Total Retail Loss (TRL) concept; an updated TRL typology offering 42 categories of loss – up from 33 in the original version – to account for losses associated with E-commerce; and a structured approach to using the typology based on the experiences of early adopters around the world. We’re optimistic that TRL 2.0 along with the original report will enable the retail industry to strive towards a more coherent, integrated and progressive approach to the management of losses and ultimately the protection of profits.

RILA is enormously appreciative to Professor Beck for his thought leadership on TRL and his partnership over the years. RILA would also like to thank Intel, Profitect and Zebra Technologies for their support and commitment to helping the retail asset protection industry achieve operational excellence. We’d like to recognize the valuable support offered by the ECR Community Shrinkage and On-shelf Availability Group, and finally, we thank the many retailers that participated in this important work.

Lisa LaBruno

Executive Vice President Retail Operations & Innovation

Retail Industry Leaders Association

Executive Summary

In October 2016, RILA published the Beyond Shrinkage: Introducing Total Retail Loss report, the culmination of many years of academic research with leading retail companies and loss prevention specialists from around the world. The report mapped out a fundamentally different way for retail companies to not only define what is meant by ‘retail losses’, but also how they might organize themselves to manage them more effectively.

Based upon a typology comprised of 33 categories of loss, focused on four key areas of retailing, it sought to better reflect the reality of risk management in a 21st Century context – one which is not singularly focused upon just one measure of loss, but is capable of navigating the complex and rapidly changing retail world of today.

Since its publication, the global retail loss prevention community has had the opportunity to reflect upon this different way of thinking about the management of loss – does it make sense, is it manageable, and above all is there any real value in adopting this type of approach? The purpose of this report is to offer reflections on how Total Retail Loss (TRL) has fared moving from an essentially theoretical proposition to the practical realities of the real retail world. In particular, the research was interested in considering five factors: Awareness (do retailers know of its existence?); Adoption (to what extent have they begun to use it?); Review (is the original typology and concept fit for purpose?); Development (how should it change to meet the current retail context?); and Implementation (what advice should be given to those thinking about adopting it?). The research was based upon an online survey aimed at major retailers in the US, Europe and Australasia and in-depth interviews with senior loss prevention executives.

The key findings from this research can be briefly summarized as follows:

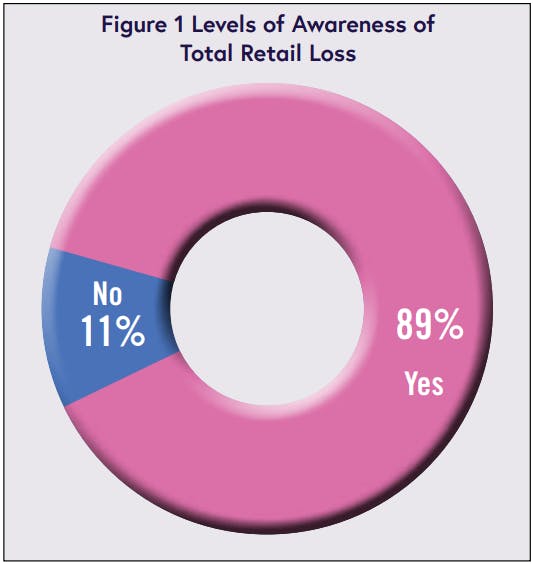

Awareness: Of those surveyed, levels of awareness of TRL were very high – 89%. Of those that were aware, two-thirds were of the view that it had led to some form of impact in their organizations.

Adoption: Over one-half of respondents (53%) stated that they had either fully embraced the concept or adopted some of its elements. A further one-quarter (24%) were thinking about using it in the next 12 months.

Review: The research found that companies were engaging with TRL because it: provided a better framework to capture all forms of retail losses; created opportunities to positively impact on business profitability; helped to ensure resources were more effectively targeted; enabled the loss prevention function to maintain relevance; created greater transparency and accountability; and helped to manage increasingly complex retail environments. The original 33 categories of retail loss were found to be both applicable and relevant to the retail environment.

Development: The research enabled a revised TRL typology to be created, which further developed the categorization of losses associated with E-commerce retail platforms. The typology has evolved to now encompass 42 categories of loss.

Implementation: Early advocates and adopters of TRL provided a wealth of feedback on their experiences of using it, offering 12 key issues to consider when thinking about embarking on a TRL focused journey:

- Get the C-suite Onboard: Like most significant change initiatives, senior management support is key – generating urgency, facilitating financial support and ensuring compliance – all are important in making a TRL-based strategy a success.

- Develop a Business Case – Focus on the Size of the Prize: Making use of the available data and the organization’s appetite for change, build a strong business case that focusses on the financial benefits that might accrue from adopting a TRL-based approach.

- Adopt an Incrementalistic Approach to TRL: The TRL typology should be viewed as a palette of possibilities that can be tailored to any given organizational context – start small and build gradually – it is very easy to take on more than is realistically manageable in the first instance.

- Identify Quick Wins First: At the beginning, only focus on those areas of loss that are likely to generate successful outcomes and are readily deliverable – do not attempt too much too soon.

- Organize for Utilizing TRL: Think about who will be accountable for delivering a TRL-driven approach, what resources might be required (particularly analytical) and how to leverage support from across the business.

- Advocate for TRL – Act as Agents of Change: Pooling responsibility for the management of all the areas of loss covered in TRL is less than desirable. Ensure that those driving TRL act as ‘agents of change’ – collecting the data, prioritizing the work, and then recommending ameliorative actions to those best placed to deliver them.

- Review Reporting Structures for TRL: While there is little standardization on lines of reporting across the loss prevention industry, given the breadth and scope of TRL, a number of respondents to this research argued strongly that the Finance function is best placed to provide overall coordination.

- Prepare for Organizational Antagonism: The way in which TRL often cuts across a wide range of organizational responsibilities can cause the potential for functional disquiet based upon a perceived ‘land grab’ by those driving the TRL agenda. It is important, therefore, that an assessment of the likely reaction of those impacted by a TRL initiative is undertaken, with a view to taking pre-emptive actions to explain, reassure and support.

- Think About the ‘Right’ Name for your TRL: While the phrase Total Retail Loss has become relatively well known in the global loss prevention community, it is important that individual organizations develop their own label for their TRL-inspired initiative, based upon their particular circumstances and context. For a number of respondents, moving to ‘Profit Protection’ was regarded as a useful moniker that accurately described what the TRL-inspired initiative was aiming to achieve.

- Avoid Terminological Confusion: It is important that as a business embarks on a TRL-oriented journey, the language that is used is clear and focused – by all means continue to use the term ‘shrinkage’ as a proxy for unknown stock loss, but ensure that there is a clear distinction made between that and the broader loss picture that you are aiming to develop.

- Use TRL as an Analytical Lens: As well as providing a broad ranging and overarching framework for assessing and managing retail losses, the TRL concept can also be used in a much more focused way to evaluate the likely impact of any planned innovation and change by a business. By stimulating a more comprehensive assessment of the likely impact across a broad palette of losses, the TRL model can enable a more realistic and balanced ROI to be calculated for any given innovation or retail change.

- Remember Timing is Key: Finally, like most decisions in life and work, timing can play a huge factor in dictating the success or not of any given initiative. Reflect upon the current organizational climate and whether it is likely to be broadly receptive or not to the introduction of a TRL-based approach. Where the head winds are deemed to be too strong, and other priorities too dominant, then delay may well be right approach.

Background and Context

In October 2016, RILA published the Beyond Shrinkage: Introducing Total Retail Loss report, the culmination of years of research work focused on helping the retail industry to develop a more overarching and fit-for-purpose definition and typology of the full range of losses that it experiences (1). Since then, the Total Retail Loss (TRL) concept has received critical acclaim across the globe, not only for the way it has encouraged a broader more wide-ranging debate about what constitutes retail ‘loss’, but also its review of what the future role and responsibilities of the ‘loss prevention’ function might/should be.

As a theoretical idea, it has received considerable academic and industry support, and in many respects, it is difficult not to agree with the underlying premise – that the existing definition of loss, focused almost exclusively upon ‘shrinkage’, a loose and ill-defined term generally only covering unknown forms of stock loss, does not adequately capture the complexity of modern retailing nor the fundamentally different risk landscape it has created (2).

In addition, while the world of retail loss was once characterized as a ‘data desert’, which drove rather myopic approaches to its conceptualization and control, the range of data sources now available provide new opportunities (and challenges) to both understand and measure a much broader palette of retail losses. This is particularly the case when it comes to an area such as online/e-commerce, which has seen remarkable growth in some retail sectors (3). This form of retailing presents a whole new range of loss prevention challenges, not least how losses associated with it will be measured, but also how subsequent control interventions might be assessed for their effectiveness.

However, while theoretically appealing, TRL can also be seen as a highly disruptive and organizationally challenging concept to adopt, potentially requiring a fundamental re-evaluation of how retail businesses organize themselves and prioritize their activities. Because it can require a cross-organizational assessment of not only how losses are defined and measured, but also how they are collected, it can be difficult in the first instance to define lines of responsibility. And even when a retail business has populated the TRL typology with calculations of the monetary value of the various types of losses it proposes, developing a business strategy to then focus upon those areas of loss likely to reap the greatest rewards can be equally challenging. With the TRL typology spanning across losses occurring in physical stores, supply chains, e-commerce activities and central business functions, achieving agreement on who is responsible for co-ordinating the business response may not be easy.

Over very many years of retail organizational development, boundaries of responsibility have been developed, ring-fencing budgets, resources, approaches and priorities – the Loss Prevention team deal with ‘shrinkage’, Store Operations deal with out of stocks, Supply Chain look after losses in product movement, the Risk team deal with health and safety issues, and so on. TRL promotes a much more holistic and cross-functional dialogue to take place, potentially exposing vested interests, questioning areas of responsibility and perhaps requiring a commitment to reorganize. In some respects, it might often be much easier to maintain the status quo, particularly at a time of considerable sectoral instability and flux.

However, as the original RILA report strongly argues, the benefits of adopting TRL could be profound, not least by unlocking a considerable amount of lost profits at a time when retailing is struggling to maintain currently levels of profitability – it offers a persuasive case at a time of sectoral dislocation. Indeed, a number of retail companies around the globe have begun to adopt TRL (or versions of it) while many others would appear to be in the process of assessing how they might go about doing this. Certainly, references to ‘Total Retail Loss’ as a concept at international retail loss prevention conferences and workshops is becoming much more common, suggesting that it may well be getting more and more traction amongst the loss prevention retail community.

What is not clear though is how and in what ways adopters have gone about using the TRL concept, nor is it clear the extent to which they have adapted the TRL typology to fit their particular circumstances. Do the 33 categories of loss outlined in the original typology actually make sense for retailers – are they all relevant, or are some missing? Equally, it is not clear how any given company responded to the introduction of TRL – did any re-organization take place, and if so how? For those considering but as yet not deciding to implement TRL, what are the barriers and what information and help do they require to drive their adoption forward?

Moreover, as retailing evolves, and information sources develop, is the current typology still fit for purpose or should it be updated to take account of these changes? It is within this context that the current report is framed: to what extent is it being used; what are the experiences of those who have adopted TRL; what are the challenges of those seeking to adopt it; and how does TRL need to evolve to take account of its exposure to the ‘real’ retail world?

Report Objectives

The research presented in this report had the following key objectives:

- Understand the extent to which the global retail community (in particular, but not exclusively, in the US and Europe) is aware of the TRL concept.

- Review the degree of TRL adoption, including the format in which it is being used and the reasons put forward for its use.

- Consider existing retail attitudes towards the applicability of TRL to understand losses in the retail sector.

- Based upon the experiences of current and prospective users, review how TRL has changed the way in which loss is both understood and measured in retail businesses; its impact upon organizational structures, lines of responsibility, and where applicable, approaches to managing loss.

- Review the applicability of the existing TRL typology and make changes to take account of user experiences and new developments in retail loss, in particular, E-commerce.

- Develop insights to facilitate those who are thinking about using TRL.

The report is structured around a number of themes relating to these objectives. The next section briefly summarizes the research method used to carry out this research. It is then followed by a section looking at levels of awareness of the concept of Total Retail Loss. The next section then focuses upon the extent to which retailers are utilizing the concept, including their rationale, perceived benefits and the function most likely to take the lead.

The next section then looks at the perceived barriers, concerns and challenges to adopting Total Retail Loss, focusing particularly on issues of data availability and reactions from other parts of the business. This is then followed by a review of a revised Total Retail Loss typology which incorporates the results from this research. The penultimate section then provides a detailed consideration of what those who might be thinking about embarking on adopting the concept need to consider to make it more likely to succeed. The final section then provides a brief conclusion, bringing together the main elements reviewed in this report.

Methodology

The project utilized two main methodologies to deliver the objectives of the research: an online survey of retailers; and interviews with loss prevention leaders.

On line Survey: Through links provided primarily by the Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA) in the US, the ECR Community Shrinkage and On-shelf Availability Group in Europe, and the Profit Protection Future Forum (PPFF) in Australia, a database of loss prevention executives was compiled of the largest retail companies (by retail sales) in the US, Europe and Australasia. In addition, help was sought from representative retail bodies within a number of European countries to solicit the names of loss prevention leaders, and finally, the survey was also advertised on a number of loss prevention-related blogs and forums.

Only larger retail companies were targeted for two reasons: first, the very nature and relative complexity of the Total Retail Loss typology was thought to be much more relevant and applicable to these retailers; and secondly, identifying the head of loss prevention is far more straightforward in these organizations as they are predominately well represented in trade groups such as RILA, ECR and PPFF.

The survey was made available for completion between January and March 2019. In total 225 companies were contacted to fill in the online survey, with 92 providing a useable response (41%). Despite repeated efforts to increase the number of retailers from mainland Europe and Australasia, the sample is dominated by retailers from the US and the UK (80%). Clearly, given the scale of global retailing, in no way can this be regarded as a representative sample – it is much more representative only of large retail organizations that contribute to particular trade bodies in certain countries. As such caution needs to be applied when considering the results from this survey.

In-depth Interviews: The second methodology utilized was interviews mainly with heads of Loss Prevention in those companies that agreed, as part of the online survey, to provide further information about their experiences and thoughts relating to TRL. Of the 92 responses to the online survey, 58 offered to provide further information and of those 17 were interviewed. These were selected to represent a range of levels of adoption of TRL: fully aligned; adopted some elements of it; thinking about adopting it; and no plans to use it in the near future. Almost all the interviews were conducted via Skype (two were completed face-to-face at a loss prevention conference) and lasted between 30 and 45 minutes. All were taped and transcribed at a later date. Throughout this report quotes from individual responses will only be identified via a Research Interview (RI) number and this number will change for each respondent in each section of the report to ensure anonymity is preserved and no links can be drawn between similarly numbered quotations.

In addition to the online survey and in-depth interviews, interviews and follow up correspondence was undertaken with a number of loss prevention specialists with an interest in E-commerce. As detailed later in the report, the original iteration of the TRL typology had few categories of loss covering this topic – just Customer Frauds and Credit Card Chargebacks. The research was therefore interested in understanding whether more categories could/ should be included in any new version of the typology. The researcher is very grateful to those that agreed to help out with this aspect of the report.

As with most research on retail loss, collecting data and ensuring it is representative is not easy and this project has been no different. However, I am very grateful to representatives from the following companies for agreeing to help out with this work: American Eagle; Best Buy; Footlocker; GameStop; Helzberg Diamonds; Home Depot; Lowes; Macy’s; Meijer; Reiss; Sainsbury’s; The Gap; Southeastern Grocers; Ulta Beauty; Waitrose; Walgreens, Walmart International; and Whole Foods Market.

Reviewing Retail Awareness of Total Retail Loss

This section considers the extent to which respondents to the online survey were aware of the concept of TRL, if they were, how had they become aware of it, and finally whether this awareness had led to any noticeable change in the way in which their businesses managed retail losses.

Awareness of Total Retail Loss

As can be seen in Figure 1, of those responding to the survey, a very large proportion were aware of the TRL concept – almost 9 in 10 said that they had heard of it (89%). Only a small minority, just 11% claimed not to have heard of it. This would suggest that the dissemination and publication of the TRL concept had largely been successful, certainly amongst the major retailers participating in the survey.

Sources of Awareness of Total Retail Loss

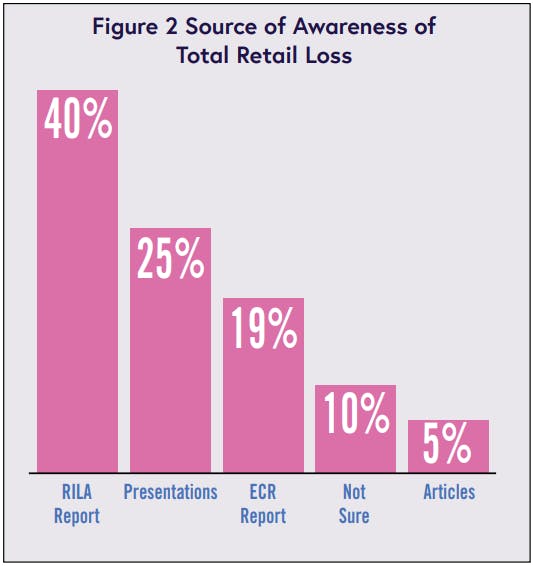

Respondents were then asked to indicate how they had first heard of the TRL concept (Figure 2). For almost two-thirds of respondents (59%) they had become aware of it via either the RILA report, which was published in October 2016 or the subsequent abridged ECR version which was published in December 2016. A further one-quarter (25%) had been made aware of the concept through listening to presentations, either in person or via a webinar.

Finally, only a very small percentage of respondents (5%) had first come aware of the concept from articles in practitioner or academic publications (4).

Impact of Awareness

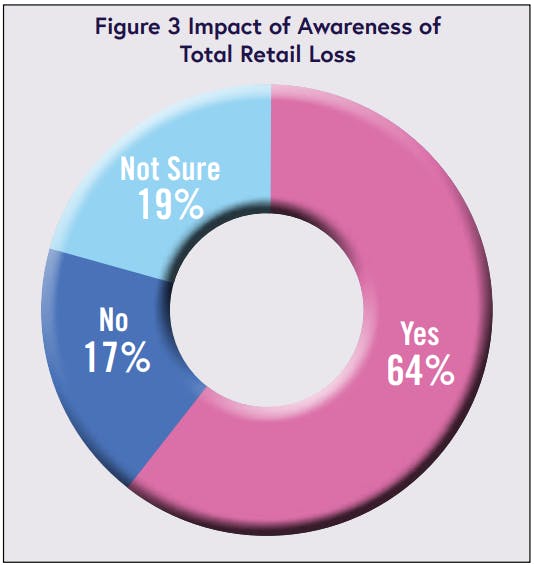

A final question on awareness of the TRL concept asked respondents to consider whether becoming aware of it had had any demonstrable impact on the way in which their businesses now viewed and responded to the issue of retail losses. Of those who were aware, two-thirds (64%) thought that it had had an impact, while 17% thought the opposite. Finally, approximately one in five were unsure whether becoming aware of the concept had made any difference to the way in which their companies now operated (19%). The ways in which respondents thought that becoming aware of the TRL concept had made an impact will be considered in more detail in the next section of this report.

Overall, it is encouraging that of those participating in the online survey there was such a high level of awareness (90%) and that of those, two-thirds were of the view that it was making an impact in their organizations (64%). The next section will now go on to consider in detail how those who were aware of the concept were utilizing it within their businesses.

Understanding the Utilization of Total Retail Loss

This section looks in detail at how retailers who participated in the online survey and those who agreed to provide additional information via in-depth interviews were utilizing the TRL concept. It will look in detail at the following areas: the extent to which respondents had adopted it or were planning to adopt it in the near future; the reasons why it was being adopted; the perceived benefits of engaging with the concept; the outcomes of its utilization; who had taken the lead on developing it within the business; and finally whether adopters had been successful or not in calculating a TRL number.

Current Levels of Adoption

Outlined in Figure 4 are respondents’ assessment of the extent to which they had adopted the TRL concept. As can be seen, only a small minority were of the view that they had fully embraced the concept (10%), with the largest proportion (43%) suggesting that they had taken on board some elements of the concept. For a further one-quarter (24%) it was something which they were planning to use in the foreseeable future while a similar proportion had decided not to adopt the concept (24%).

In many respects, this is a very encouraging outcome – three-quarters of all respondents to the online survey who were aware of the concept were either utilizing it to some degree or were planning to do so (76%). It was not possible to find any statistically significant difference by type of retailer and level of adoption. Of course, understanding why and to what extent the 43% who had adopted some elements of TRL is important to understand, and is something that will be returned to later in this report. However, overall this is an encouraging result and suggests that the TRL concept has gained a reasonable degree of traction, certainly amongst larger retailers.

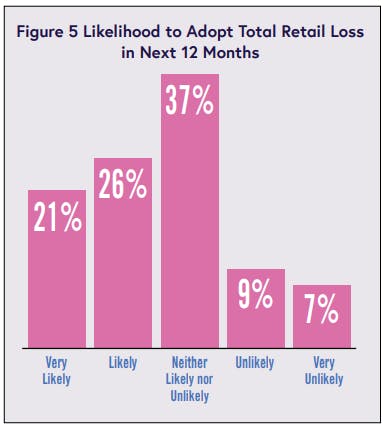

Those who had indicated that they were thinking about using the model or had no plans at the present moment to use it, were asked an additional question focused on their likelihood to begin using the concept in the next 12 months (Figure 5).

As can be seen, nearly one-half (47%) were of the view that it was either very likely or likely that they would begin to use some aspect of TRL in the next 12 months. A further 37% were not sure while 16% considered it unlikely or very unlikely that the concept would play any role in their organization in the next 12 months. Again, these results are encouraging, suggesting that there is growing interest and planned adoption amongst retailers of the TRL concept.

Rationale for Engaging With Total Retail Loss

Those respondents who had indicated that they had adopted some or all of the TRL concept were then asked to explain in more detail why they had decided to do this. In the first instance, responses were collected via the online survey (Figure 6) and this was supplemented by more detailed questions as part of the in-depth interviews. The survey results point to a number of key reasons (respondents could select more than one option), the most frequently selected being that the concept provided a better framework to capture all the losses that businesses were now experiencing (78%). The second most popular response related to the way in which the model offered greater opportunities to make a positive impact on business profitability (67%). This was then followed by its capacity to help organizations target their resources more effectively (58%). The least chosen reason for adopting TRL was that the business now had the data to enable it to be utilized (50%).

In many respects these initial results are perhaps not surprising – one of the key objectives of developing the TRL concept was to provide a much more overarching and inclusive conceptualization of how losses were being experienced by retail organizations. In turn, it argued that by doing this, businesses would be able to boost profits by being able to target resources more effectively on the areas that might generate the greatest impact.

Enabling Loss Prevention to Remain Relevant

While these factors were also highlighted in the in-depth interviews, it also became very apparent that the TRL concept was also viewed by many as a way to ensure that the Loss Prevention function continued to be viewed by the rest of the business as both relevant and of value. This was graphically illustrated by a number of those interviewed:

Most companies are getting towards historical lows for shrinkage. We are now thinking OK we have taken care of shrink, now what is next? All of us in the industry need to be thinking what is next? It has got to go beyond just merchandise and cash loss. How does loss prevention remain relevant in a retail world which is changing so much? [RI1]

Others made the point more starkly: ‘If the only thing behind my name in five years is loss prevention, then I am probably going to be out of a job!’ [RI6]; ‘If you don’t take this on you won’t have a job; I don’t think that there are many who don’t think this’ [RI8]; ‘if you don’t evolve then you find yourself behind and frankly eliminated’ [RI5]. Another respondent highlighted the need to keep up with changes in the retail environment and how the TRL concept enabled them to position themselves to make a more recognizable contribution to business profitability: ‘TRL offers a way for business survival – maintain relevancy and make a bigger contribution to the business’ [RI6].

For one respondent operating in the Grocery sector, the way TRL broadened their sphere of influence was viewed as particularly important:

We also said that LP should be responsible for perishable and waste. That probably meant the most – really signaled to the organization that AP is changing the philosophy about how we think about loss in terms of our overall operation. That absorption of an area of the business that is not typically regarded as malicious – probably sent the largest message to the business that we are thinking about loss in a different way than what we have done historically [RI7].

Finally, for one respondent, the TRL concept crystalized the need for retail loss prevention to evolve: ‘You can’t get away with the same stuff you did 30 years ago – just chasing everybody down, bagging and tagging, catching shoplifters’ [RI12].

Perceived Benefits of Total Retail Loss

Respondents to this research highlighted a number of ways in which they believed the TRL concept was bringing value to their businesses.

Better Manage Retail Complexity

As detailed in the original research report, the world of retail is evolving quickly with new formats, modes of shopping, methods of payment and above all, greater choice being provided to the consumer, creating ever more complexity in the retail environment. In turn this complexity inevitably leads to not only an increase in risk but also exposure to a greater range of risks. As detailed above, gone are the days when loss prevention was exclusively focused upon, and held responsible for, dealing with external theft. The palette of potential losses is now much greater and so a number of respondents argued that the TRL concept provided a much more expansive and inclusionary framework that helped them better manage this more complex and challenging retail world. As one respondent put it: ‘Main advantage – enable you to identify where a company is experiencing losses and then direct and guide pyramid heads to respond to them; act as a road map about where AP [Asset Protection] and others need to go next’ [RI11].

Generate Greater Transparency and Accountability

As the range of retail risks grow then the need for an ever more cross functional response becomes apparent: ‘It allows you to spread the ownership to the business rather than just sitting in one place and others blaming AP to fix the problem; instead AP can go to other functions and say hey what’s your part in fixing this problem?’ [RI16]. The issue of accountability and organizing to deliver TRL will be returned to later in this report.

In addition, by attempting to measure all forms of retail loss, the TRL concept is designed to try and remove opportunities for retail functions to redefine losses into non-accountable categories, for instance shift shrinkage losses in to wastage if the former is a leading indicator. As one respondent put it: ‘[It] has provided much more transparency and clarity about how stores are really performing, taking account of all [emphasis added] the costs/losses they have suffered’ [RI5]. Another flagged up how by using a broader range of indicators the business was now getting a more complete picture of store performance: ‘So some stores have in the past been viewed as doing very well because they have low shortage numbers, but now when more areas of loss are considered, they are not seen as doing so well’[RI9]. For another respondent, the same was going to be true for the loss prevention team: ‘We used to calculate our review based upon shortage and case activity [incident investigations] based upon shortage; in 2019 we will look at case activity compared against TRL … store LP teams will be benchmarked against TRL’ [RI17].

Create New Opportunities to Reduce Retail Losses

Respondents to this research also highlighted how they thought the TRL concept, by enabling them to identify a broader palette of losses, provided more opportunities to reduce retail losses and in turn increase business profitability. One of the companies that had fully embraced the concept was prepared to put a value on the difference it had made: ‘In less than 3 years we have created many millions of dollars in incremental value to the business; from a standing start this is not bad at all’ [RI16].

Maximize the Potential of the Loss Prevention Team

As detailed above, one of the drivers for the Loss Prevention function in particular to engage with the concept was a sense of ensuring that they remain relevant and of perceived value to the business:

We have been very successful over the past few years on a shrink perspective. Frankly we are now looking for ways to add value to the organization to stay relevant… this provides us with an opportunity to do that [RI3].

Moreover, it was also viewed as enabling ways to make the case to utilize the current skill base within the loss prevention team more broadly: ‘I’m saying hey, we have a team that is trained on reducing loss, look at all the ways in which they could contribute to the organization and here is the business case for it; in some respects TRL offers a way to make a bigger contribution to the business’[RI6].

Utilize Organizational Resources More Effectively

Another benefit of the TRL concept identified by the in-depths interviews with loss prevention leaders was its impact upon enabling the business to reflect upon, and make better use of, current resources. As one respondent put it: ‘by painting the bigger picture we now have more of a sense of where we might get a bigger bang for our buck – what should we chase down next with what [resources] we’ve got’ [RI3]. This was certainly the case for those businesses that had been able to populate the TRL typology and begin to compare and review identified problems with currently allocated resources: ‘we didn’t realize how big some of the other areas of loss were and how little resource we had allocated to try and fix them’ [RI7].

Enable the Business to Better Understand Retail Losses

A considerable number of interview respondents commented upon the value of using TRL as a means to ‘educate’ the rest of the business about what retail losses are and how they are affecting the organization:

The one thing that TRL does is that it helps leaders like me communicate to our teams and others that LP [loss prevention] is not just about shrink, or merchandise loss or cash loss … we now have an impact on out of stocks and lost sales, that we have an impact on operational losses/paper shrink, losses in the e-commerce world; it offers a really nice one page picture of how AP [Asset Protection] supports the business. It allows us to tie it all in. We use it as a way of explaining to people how to understand losses and how they impact upon the organization [RI11].

For another, the typology offered a useful way to bring new hires up to speed on how loss is understood: ‘So when we on-board people we take them through TRL to show how loss impacts on the business’ [RI11]. Using TRL as an awareness raising tool was evident across a number of participating retailers and seemed to be offering value in terms of helping to educate others about their role in managing losses:

For [store] operators it proved a good way to show them that all their actions have consequences and so it drove ownership. Helped us find the common denominators across the stores, especially where the cause was not in the control of the stores – so merchant behaviors for instance. Helped us understand that it is much easier to fix the root cause then keep putting a sticking plaster on the problem in each of the stores affected by it. Engaging the merchants was a key factor – it has freed up more hours in my [loss prevention] team than anything else that we do. Helped us stop fighting fires [RI7].

Outcomes of Adopting Total Retail Loss

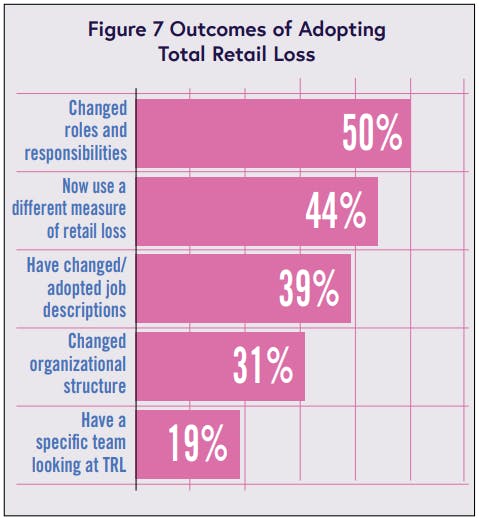

As part of the online survey, those respondents that indicated they had adopted TRL to some degree were asked to consider how this adoption had led to change in their businesses (Figure 7).

As can be seen, the most frequently chosen category was that it had led to a change in roles and responsibilities (50%), followed by the use of a different measure for retail losses (44%). The third most frequently chosen category was making changes to job descriptions in the business (39%). Far fewer respondents suggested that the adoption of TRL had led to changes to organizational structures (31%) and fewer still stated that they had developed a specific team to look at TRL (19%).

The ways in which those companies that had adopted TRL had changed roles and responsibilities in particular will be considered in more detail later in this report.

Responsibility for Overseeing the Adoption of Total Retail Loss

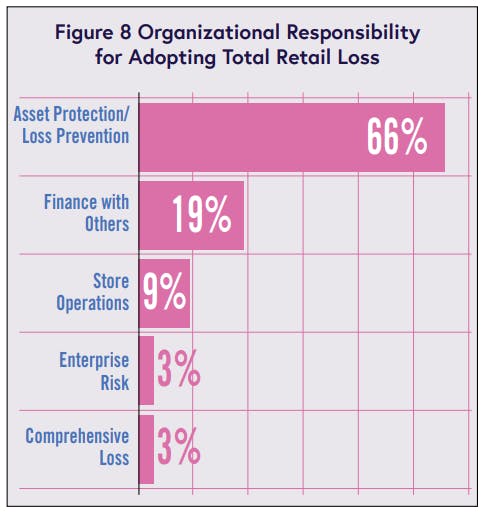

The online survey was also interested in understanding from those that had adopted to some extent the TRL concept, which function had taken organizational responsibility (Figure 8).

As can be seen, two-thirds (66%) of respondents said it was the Asset Protection/Loss Prevention function that had taken responsibility for adopting TRL. This is perhaps not surprising given that the survey had been sent to the head of this function. However, nearly one in five respondents suggested that the Finance function, in partnership with others had taken the lead role. Far fewer respondents indicated that other functions had taken a lead role, with only 9% identifying Store Operations and just 3% stating it was a risk-related function or an actual TRL-focused group.

Given the nature of the TRL concept, which is fundamentally about retail loss, it is therefore not surprising that the Loss Prevention team is the most likely to take a lead when it comes to introducing/ managing TRL into the business. However, as will be discussed later, given the scope of TRL and the way in which its tentacles potentially stretch across organizations, requiring the collection of data points from a myriad of functions, it is interesting to note the role Finance can play in developing the TRL concept.

Calculating the Total Retail Loss Number

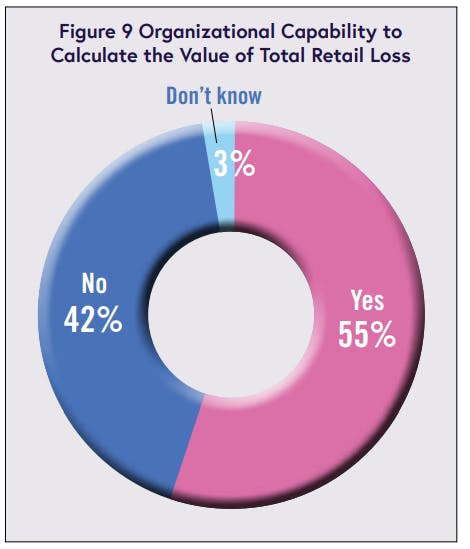

The final part of this section looks at the online responses to questions relating to the capability of TRL-adopting organizations to measure the value of the various categories of loss that make up the TRL typology. The first question was interested in understanding whether respondents felt they had the organizational capability to calculate the value of TRL (Figure 9).

Of those who claimed to have adopted TRL to some extent, just over one-half said that they had the capability to calculate the value of TRL (55%) while four in 10 said that they were not able to do this (42%). What the question does not answer is whether this capability is limited by a lack of data and/or an organizational willingness to undertake this type of activity.

Certainly, some of the in-depth interviews highlighted issues relating to this, in particular a lack of current prioritization: ‘I don’t think that there is an appetite to take on the big number – there are simply bigger priorities elsewhere at the moment’ [RI4]; ‘Never tried to calculate the [overall] TRL number – it would be nice to do but with so many competing priorities it is difficult to justify the effort to calculate the number’ [RI11]. For others it was more about the challenge of pulling numbers together from across the business: ‘Still a challenge for the business… we haven’t come up with a way to come up with one number yet, still very compartmentalized’ [RI1].

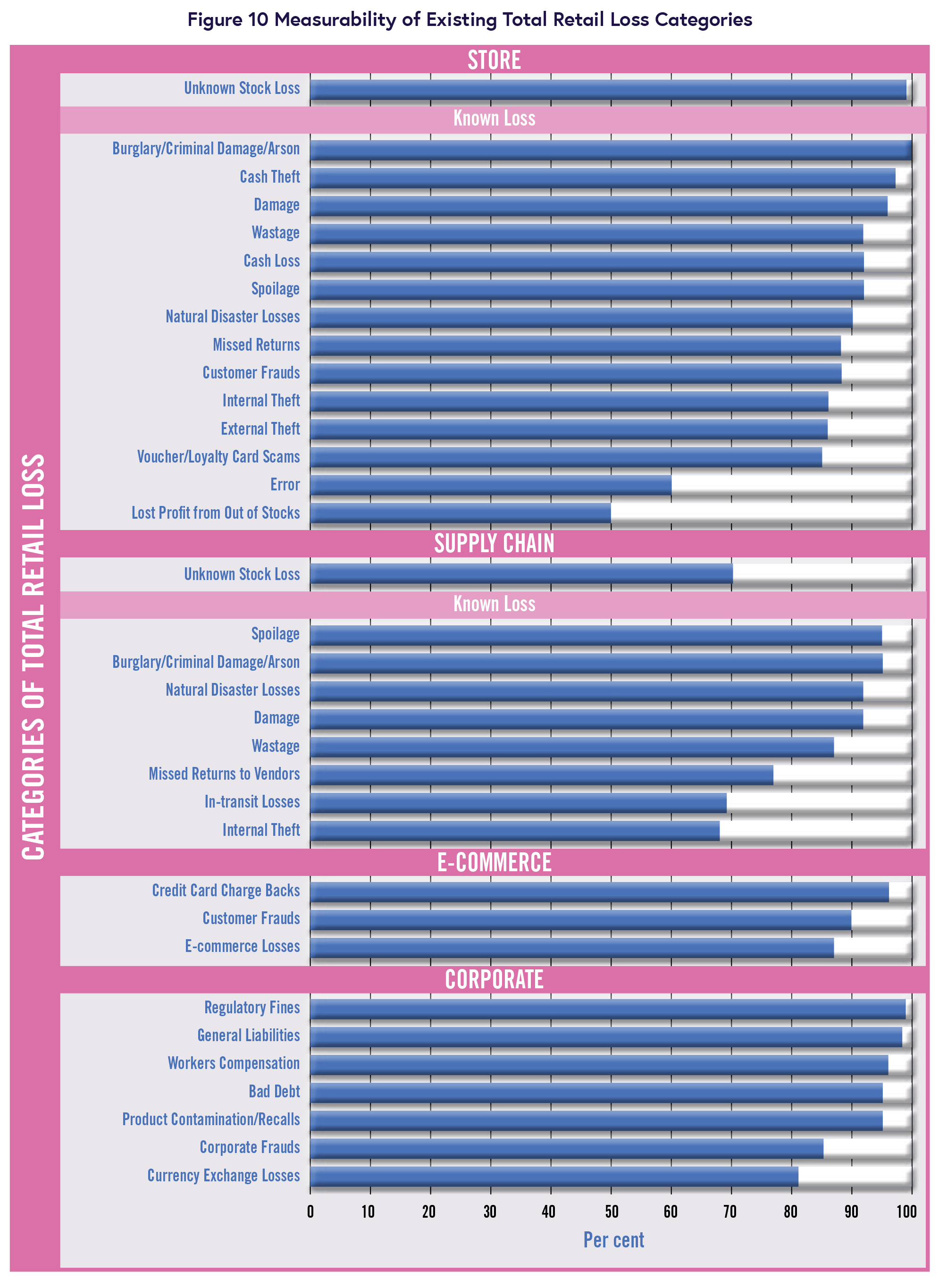

The data-related issues and challenges associated with TRL will be discussed in more detail in the next section, but the on-line survey also asked respondents to indicate the extent to which their organizations held data on the 33 categories of loss outlined in the original TRL typology (Figures 10 and 11) (5).

The chart is broken down into the four Centers of Retail Loss identified in the original report: Retail Stores; Retail Supply Chain; E-commerce; and Corporate. Under each of these headings, respondents were then asked to state whether their organization was able to routinely measure the various types of loss included in TRL.

Starting with physical retail stores, perhaps unsurprisingly, the vast majority of respondents stated that they collected data on unknown losses (shrinkage) data (99%). This is loss data captured when routine stock audits are carried out and summarizes the difference between expected and actual stock levels/value. The TRL typology is then made up of 14 categories of known losses that occur in retail stores. The average score for all respondents across these categories was 86% claiming they did collect data on them although there was considerable variance by type of category.

For seven categories (Burglaries/Criminal Damage/ Arson, Cash Theft, Damage, Wastage, Cash Loss, Spoilage, Losses from Natural Disasters) 90% or more of respondents said that they routinely collected data on them. For a further five (Missed Returns, Customer Frauds, Internal and External Theft, Voucher/Loyalty Card Scams) there was also relatively high levels of availability – 85-88% or more of respondents.

There were only two categories that received a much lower score – Errors and Lost Profit from Out of Stocks (60% and 50% respectively). These are both understandable, certainly in terms of getting accurate and reliable data on the extent to which they impact upon retail stores (6).

With regards to the Retail Supply Chain, fewer respondents claimed to be collecting data on Unknown Losses that occurred in this environment compared with Retail Stores (70%). Given the relative complexity of undertaking audits in supply chain environments, this lower number is perhaps not unsurprising. As can be seen summarized in Figure 11, the overall rate of collecting data on known losses in the Retail Supply Chain was 84%, slightly lower than that found in Retail Stores. Again, there was considerable variance by category of loss. Five categories scored relatively highly – between 87% and 95% (Spoilage, Burglaries/ Criminal Damage/Arson, Losses from Natural Disasters, Damage, Wastage) while three were much less likely to be collected (Internal Theft, In-transit Losses, Missed Returns to Vendors).

In terms of the categories for E-commerce, as can be seen, the original typology had relatively few – just two: Customer Frauds and Credit Card Chargebacks. This was a function of the relative inability of companies participating in the original research to be able to measure more completely the losses they felt they were experiencing from their E-commerce activities.

What is interesting, and something which will be discussed in more detail later in this report when a new typology is presented, is that overall, 91% of respondents thought that they were now collecting data on these issues. This may be a function of the growing importance not only of E-commerce to retail organizations since the first TRL report was published, but also a growing realization that it is an area of growing concern when it comes to retail losses.

The final Center of Retail Losses in the original TRL typology summarized categories of loss that could be seen as relating to the broader activities of the business, beyond those necessarily occurring in Retail Stores, the Retail Supply Chain or E-commerce, or where the overall loss is not allocated directly to these centers.

Focused only upon known types of loss, respondents indicated that there was a high level of data collection across them (93%). All scored above 80%, with five categories scoring in the mid to high 90s (Regulatory Fines, General Liabilities, Workers Compensation, Bad Debt, Product Contamination/Recalls).

In many respects this summary data validates the original selection of the 33 categories of loss – only two scored less than 70% for respondents stating that data was routinely collected on them in their businesses. These were both in retail stores – Lost Profit from Out of Stocks and Store Errors. Certainly, the former remains a challenge for many companies to calculate with any accuracy while the latter can easily be concealed within the Unknown Loss number. However, as will be discussed in the next section, availability of data may not necessarily be the problem retailers face in utilizing the TRL concept – the challenge is often more about the capability to bring it together from across the organization.

Barriers, Concerns and Challenges to Adopting Total Retail Loss

While the previous section focused upon the reasons why some retail companies had decided to adopt the TRL model, and the benefits that they believed they had accrued from doing so, the original report recognized that it was a potentially challenging journey to embark upon. Use of the term ‘Shrinkage’ to summarize various types of retail loss stretches back over 150 years and it has undoubtedly been the dominant driver of the management of retail losses ever since.

It is therefore worth reflecting upon the views of respondents to the online survey and those that participated in the in-depth interviews to understand what some of the barriers, concerns and challenges to adopting the TRL might be.

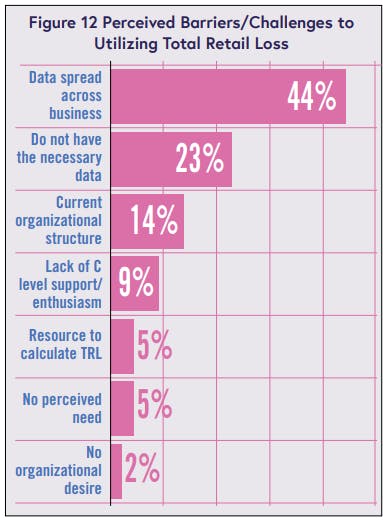

The starting point was two questions included in the online survey which asked respondents to identify the barriers and also the challenges that retailers may face when thinking about introducing TRL to their business. Summarized in Figure 12 are the results from these overlapping questions.

As can be seen, challenges relating to data occupy the top two categories – data being spread across the business (44%) and not having the necessary data (23%). This is then followed by issues relating to the current organizational structure (14%). Other issues were much less prevalent – less than one in ten felt that a lack of senior management support was a barrier (9%) while a lack of resource or perceived need or desire to embark on a TRL journey were not considered to be key concerns.

Challenges of Accessing Retail Loss Data

While the previous section highlighted the extent to which respondents felt that their organizations routinely collected information across a wide range of the categories that make up the TRL typology, it is clear from responses to these questions and the in-depths interviews that the problem is not necessarily one of data generation, but more one of data availability, accessibility and collation: ‘This was probably one of the biggest challenges we faced; we have data everywhere, loss data is all over the place, so getting the data is the more difficult part of this process’ [RI5]. Another respondent made a similar point: ‘Data is scattered across the business and then equalizing the numbers to make them comparable is tough; need to prioritize which categories make sense to the business’ [RI14].

Taking a pragmatic approach to this problem was recommended by some respondents: ‘Understand what it is that you want to measure, get to the owner of that process and get the data’ [RI5]. For another it was about making compromises:

Take the data no matter which way they [other functions] give it to you in order to make it easy and then let your team digest it and put it into one simple format. If you go to another Dept. and you say I need this data and I need it in this format, you are never going to get it [RI5].

Another echoed this view: ‘That is one of the tradeoffs – if you want this [the data] then your data analytic team are going to have to carry some of the load’ [RI5]. For another respondent, the data challenge was more about making sense of the data they had available to them: ‘Our issue is not availability but more how to use it; how do you turn it into something useful?’ [RI8].

Impact of Organizational Inertia and Competing Priorities

While the main challenge to developing some form of TRL adoption was focused primarily around the issue of data availability, access, collation and assessment, other issues were raised in the in-depth interviews with those that had begun using TRL. Of particular concern was the impact of what was described as organizational inertia on the process of adoption:

Be aware of organizational inertia that has built up over time. There are hundreds of years of legacy to deal with, that’s why you need a change management input to help manage this transition [RI16].

For another respondent this was evident in the way in which the responsibility for a range of types of loss issues had become scattered across the business: ‘The challenge was that responsibility for different types of losses are spread across the business; no one entity is responsible for all of it’ [IR6]. In some respects, it can be viewed as much easier to simply maintain the status quo – why bring about this type of change when there are so many other priorities?

Of course the answer for many was elaborated in the previous section of this report, but for some it had the potential to put them in the ‘firing line’: ‘Some of my peer group [in loss prevention] are afraid of the responsibility that comes with adopting this approach – it is risky because you will be held accountable’ [RI2]. But for others there were genuine concerns that trying to address the breadth and depth of losses incorporated within the TRL concept was not the right thing to do at this time: ‘TRL was almost too much to chew off and more pressure from Board was on shrink’ [RI15].

The issue of getting cross functional ownership and involvement with the TRL concept will be addressed further in the next section, when we consider the best ways to begin using TRL.

Incorporating E-commerce

A third area of concern raised by the in-depth interviews was the issue of E-commerce-related losses and how they may or may not be included within a TRL-driven approach. As discussed previously, the original iteration of the TRL typology had very few categories of loss associated with E-commerce and yet it was argued that this was likely to become a growing focus of concern and attention. The organization of E-commerce in many retail companies, especially those where it has been added incrementally to an existing bricks and mortar strategy, meant that loss data was often difficult to disentangle from other cost-based activities. But, as the proportion of sales through this mode of retailing increases yet further, getting to grips with the associated risks has begun to be more of a priority: ‘Prior to 2016 it was impossible [to get the e-commerce loss numbers] – after that we started recording the various drivers of loss’; it [E-commerce losses] was getting expensive so we needed to have data to help understand it better’ [RI5]. One of the key challenges is being able to differentiate between E-commerce-related losses that are malicious versus non-malicious – was a claimed non-shipment genuine or an act of fraud on the part of the consumer? Getting systems in place to begin to enable this type of data collection has proved difficult for some:

The trick and the challenge is getting to a point where the business is able to measure these losses accurately and manageably. It is a challenge because E-commerce has often been built incrementally with tentacles stretching out across the business making it difficult to pull the data together [RI6].

As will be discussed in the next section, there has been considerable progress made by some companies to develop a more rigorous and robust data collection strategy relating to E-commerce activities, but for many, building out a TRL model which includes E-commerce remains a tricky challenge.

An Updated Total Retail Loss Typology

The original research argued strongly that the TRL typology should not be something that remains a rigid and unchanging representation of the types of losses that retailers are likely to experience. Like retailing itself, the typology needs to be viewed as an organic and evolving concept, capable of being updated and refined to take account of the prevailing retail landscape.

In addition, it was not developed to necessarily try and encompass every type of retail loss imaginable, but more to identify those main categories of loss that are currently viewed by retailers as being manageably measurable and meaningful to their businesses. As such, the original typology excluded a range of potential retail losses, such as losses suffered through damage to a retail brand or the selling of counterfeit products, both of which can cause real losses to a retailer, but are often difficult for many businesses to accurately measure and record. This was certainly the case with respect to E-commerce losses where the original typology had only two categories of loss – Customer Frauds and Credit Card Chargebacks. While growing as an area of concern for loss prevention specialists, many interviewed for the original research simply did not have the data to more fully understand this issue at that time and hence the typology reflected this situation.

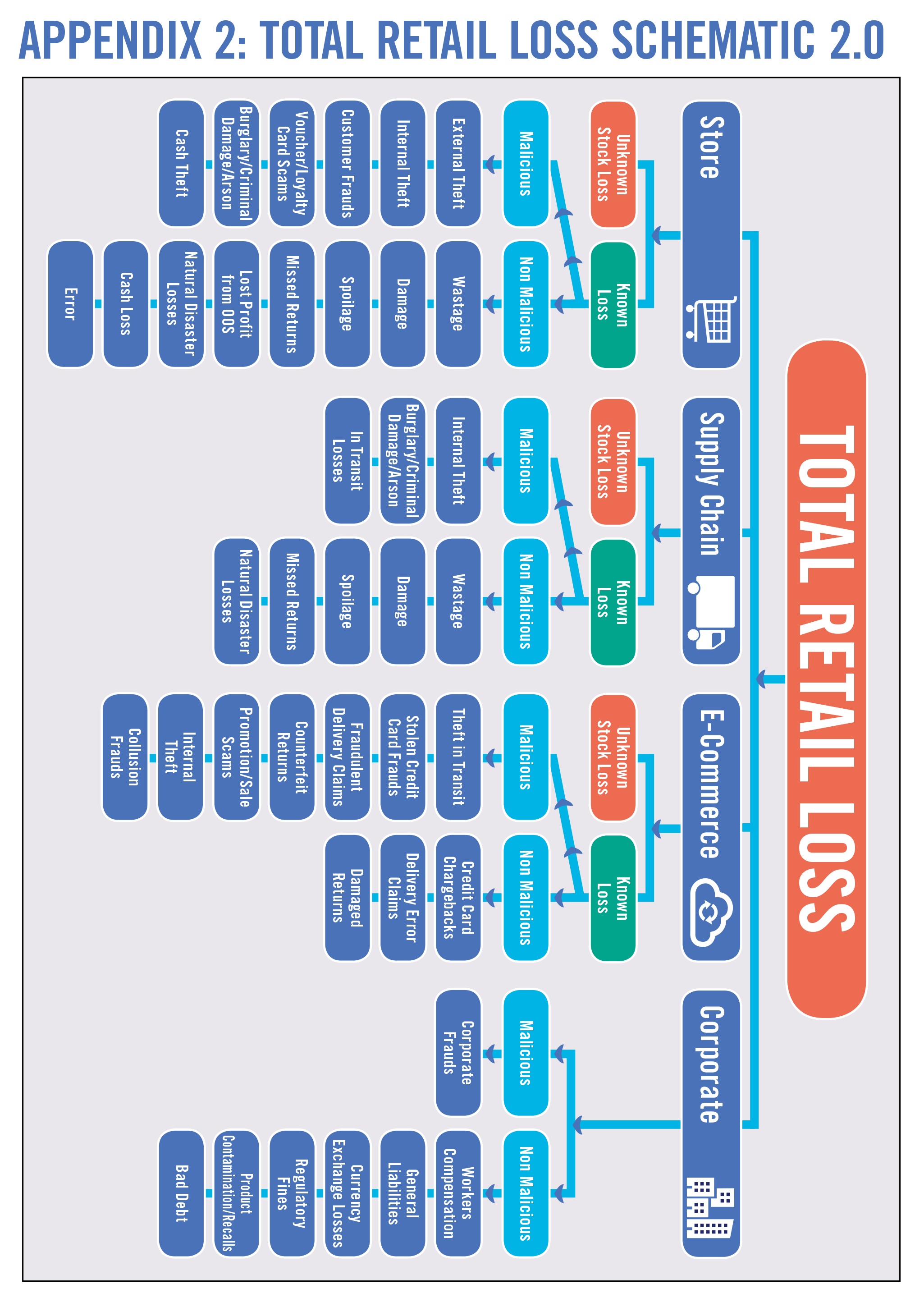

Total Retail Loss Typology 2.0

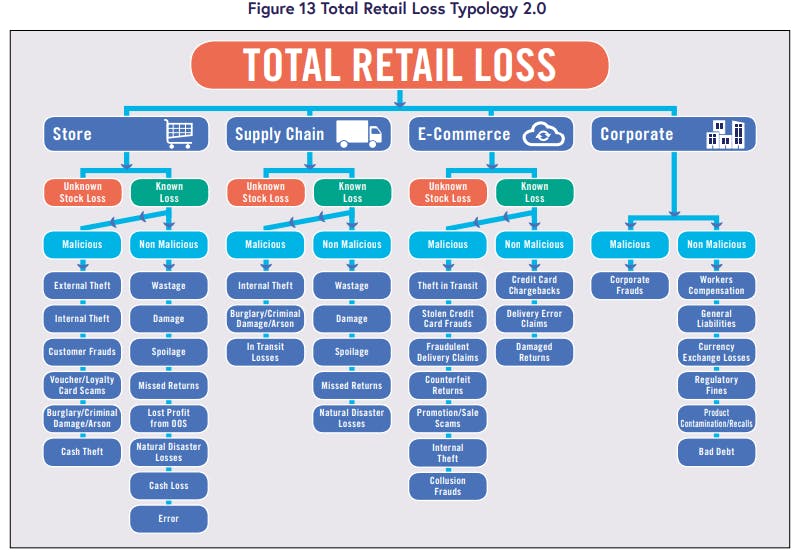

Detailed in Figure 13 is the revised and updated TRL typology taking account of the feedback from the online survey and the interviews carried out for this research. As was discussed earlier in this report, there was considerable validation of the 33 categories of loss outlined in the original typology and so they remain part of the new version. Where there has been change is in the categories reflecting the losses associated with E-commerce, which are discussed in detail below. A description of all the categories used in this typology are provided in Appendix 1.

E-commerce-related Losses

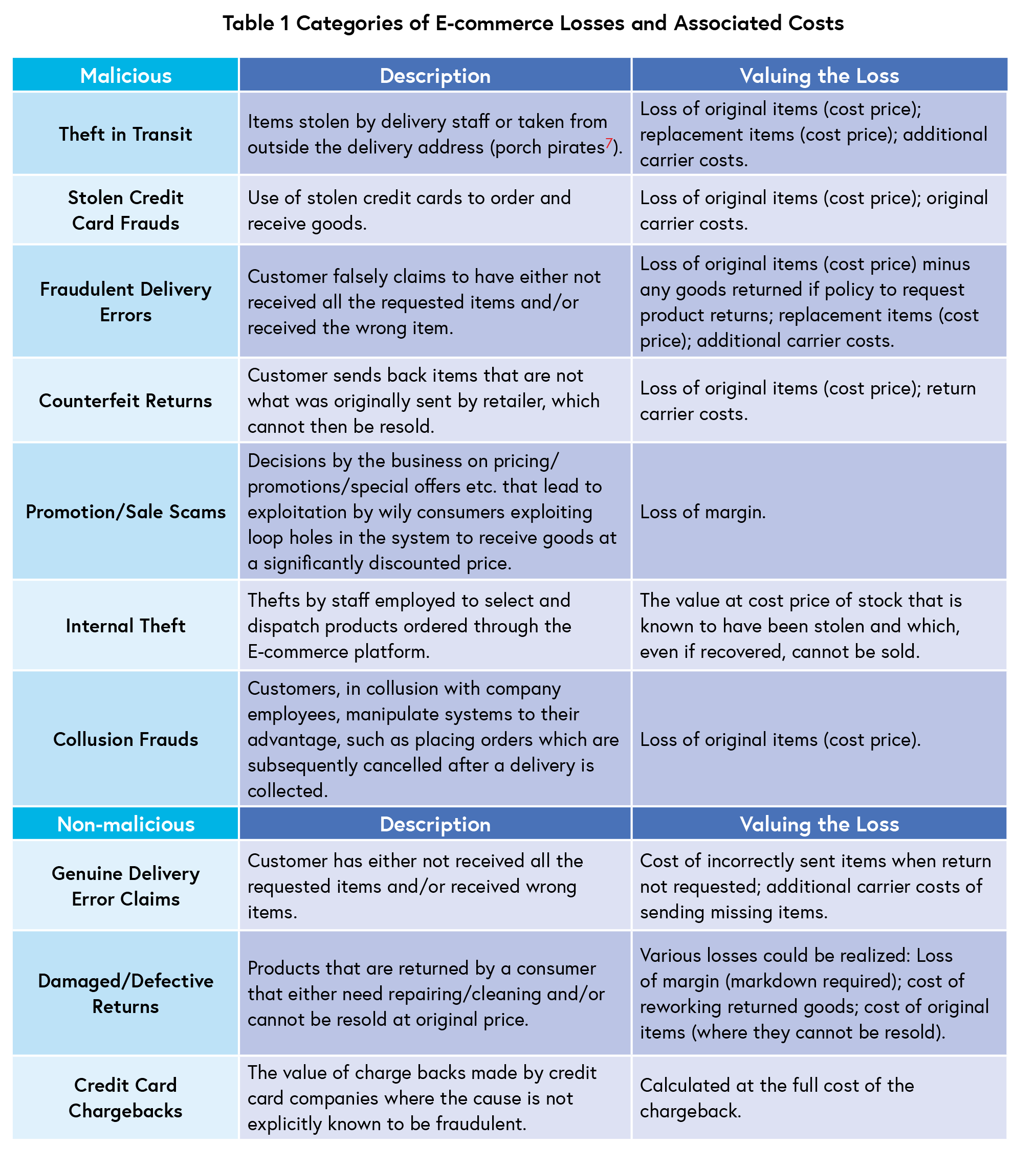

Detailed in Table 1 is a breakdown of the new categories of E-commerce losses, providing both a general description of the loss event and the factors which need to be considered when putting a value on the losses. Unlike the first version of the typology, which did not differentiate between unknown stock loss and known loss, E-commerce losses are now organized under these headings.

Like losses covered in other parts of the typology, it is recognized that there may be a considerable challenge in deciding whether losses are malicious versus non-malicious in nature. If a customer claims that an item has not been delivered, then it is impossible (for the most part) to know whether they are telling the truth or not, certainly if there is no pattern of repeat incidents or other information to verify their claim. In such circumstances it is recommended that retailers err on the side of caution in terms of codifying as non-malicious unless reasonable/verifiable evidence is available.

While these new categories may help to begin to develop a more consistent and complete picture of the losses associated with E-commerce, it is important to recognize that this remains a challenging and evolving part of the retail loss landscape.

Unpicking the losses from E-commerce remains a significant challenge to many retailers, particularly where complex fulfilment processes are in place, such as shipping from stores and offering the consumer a multitude of return pathways.

TRL 2.0: Opening Horizons with a Broader Palette of Possibilities

Taken together the new typology now offers 42 categories of loss, building upon the 33 outlined in the original version. Arguably, this is a considerable number of categories, certainly when compared with the single measure that was/is ‘shrinkage’! However, what has become very evident from this research is that few if any retailers have yet to embrace an approach which commits to using all of these categories in their loss prevention strategy. Even the 10% of companies that declared they had ‘fully embraced the concept’ in the online survey were far from populating all of the categories with a value of loss.

What is much more evident is a tailored approach to using this typology – companies reflecting upon their current capabilities, priorities, resource availability, organizational culture and appetite for change, and then creating their own, often more limited version of the TRL typology. They are selecting and, in some cases, adding categories of loss that work best for them in the current circumstances in which they find themselves. It is an approach that is eminently sensible – using the TRL typology as an adaptable resource and not an ideological straitjacket – something which can be used to trigger a broadening of understanding, taking an organization beyond the moribund strictures of only thinking about loss as a function of unknown stock loss/shrinkage.

Getting Started on a Total Retail Loss Journey

While the original TRL report was warmly received by large parts of the retail industry, those interested in exploring what it might offer to their businesses were often unsure how they might embark upon a TRL-inspired journey. What should they do first? What needs to happen for it to be a success? Who needs to be involved? What are the pitfalls to be avoided?

The purpose of this penultimate section is to try and answer some of these questions based upon the experiences of those who have begun to incorporate the TRL concept into their organizations. Detailed below are a series of factors that should be considered when thinking about beginning to utilize the TRL concept.

Get the C-suite Onboard

As with perhaps any major organizational change, the active support, and preferably involvement of, the senior executive team is critical. Indeed, for some respondents it was pivotal: ‘Not sure it can be implemented if you don’t have the C suite fully on board’ [RI3] ; ‘Exposure to the C suite was integral – be able to explain what is happening and why we should do it’ [RI6].

The key advice was to be able to explain the value of doing this – what will it bring and can we put some sort of number on it: ‘[Got to] make sure the senior management are on board – get the message across to them of the value of doing this’ [RI9]. In this respect, the TRL typology was often a useful summary document to help the senior team understand the concept – a one-page overview of where a retail business is likely to be losing value.

Develop a Business Case – Focus on the Size of the Prize

Being able to quantify the initial value of utilizing aspects of the TRL concept was also considered to be an important first stepping stone: ‘Put some numbers down on paper – if we spend this, we will get this; you have got to lay out the numbers [RI16]. Another respondent elaborated on this point and the value it provided in gaining organizational traction:

When I got back [from hearing presentation on TRL] I calculated what our Total Retail Loss could be – put a number to it and then started marketing it up the ladder. Everybody was interested in the number; everybody was agreed that we should take a look at this number and the three-dimensional approach to loss versus what we traditionally look at which is just shortage [RI15].

Understanding how to present the ‘size of the prize’ is also important to consider, for instance, for senior executives operating in publicly traded companies, expressing how the potential savings from adopting a TRL approach can impact upon Earnings Per Share (EPS) can be a very powerful message. As one respondent described it: ‘EPS is where the Senior Executive team get really excited … [showing] total impact on EPS would certainly seal the deal to make total loss a fundamental financial practice across retail’ [RI7].

As detailed earlier in this report, getting the data to begin to calculate a TRL number is often far from easy in the first instance – it can be distributed across the business and held in multiple formats – hence a good reason to begin with a relatively few quick win categories.

Adopt an Incrementalistic Approach to TRL

As detailed in the previous section, no retailer has yet been identified that is actively using all the original 33 categories of loss in their approach to using TRL – it should be viewed more as a picture of the possible rather than a reflection of retailing reality. The strong advice from many of the early advocates was to adopt an incrementalistic approach to building a TRLbased program – start small and begin to build from there:

Incremental growth is the way forward. TRL is something you can begin to build towards. We have a vision of where we want to go and how to get there, we just need to keep building on the program [RI1].

Others readily agreed, highlighting the need to only select those categories of loss that work best for the circumstances in which a business finds itself: ‘We have currently chosen categories that fit with current LP areas of responsibility; we are aspiring to get to a number that is more all-encompassing [of the TRL typology] but we are not there yet’ [RI5]. Another reflected along the same lines: ‘Put a number on what you can put a number on and build from there and then next year maybe add some additional categories as the business develops’ [RI2].

The key it would seem is to not necessarily view the TRL typology as something that should be implemented in its entirety but more as a palette of loss categories that can be mixed and matched to fit the circumstances found in any given retail environment. Moreover, start with a very clear understanding of what will work in the first instance to gain organizational traction and support and then develop and grow the concept over time.

Identify Quick Wins First

Building on this incrementalistic approach, early adopters were also keen to highlight the value of carefully selecting the categories to begin with that offered the greatest potential and were likely to offer quick wins:

We made a list of areas of the business where we felt we might have an opportunity to have an impact. We then determined who the current business owners were, then started asking questions about what they were doing to try and control it – we picked those [areas of loss] where not much was being done [RI11].

In a similar vein, another respondent cautioned against trying to do too much too soon so as to avoid the pitfalls of falling at the first hurdle: ‘Don’t try and go too broad too soon – find the categories that deliver quick wins first of all; don’t bite anything off that you are not able to impact upon effectively – find some easy wins at the start’ [RI16].

What was also evident was that early adopters were keen to avoid anything that might jeopardize how the organization more broadly viewed the TRL concept – look for areas where success was likely and wins readily deliverable.

Organize for Utilizing TRL

A very common question asked by many of those interested in starting out on a TRL journey is how should they organize to achieve this goal – who should take responsibility and what if any changes should be made to organizational structures? This is a hard question to answer definitively as corporate context has such as powerful influence on how any given business may decide to approach this issue. As such there is no one way to implementing TRL.

However, it is perhaps instructive to look at the approach adopted by one retail company that has perhaps gone the furthest thus far in implementing TRL. They created the equivalent of a Total Retail Loss Leader (8) who had overall responsibility for managing TRL across the business. In addition, they established a Total Retail Loss Leadership Coalition Group made up of senior representatives (Vice President/Director level) from each of the core business functions – Finance, Store Operations, Supply Chain, Human Resources etc.

Such senior management involvement was considered important: ‘it really helped to deal with impasses – you have the managerial clout to get things moving’ [RI17]. This group, which meets on a monthly basis, then guides the TRL work across the business – acting as a hub for TRL-related data and recording all the initiatives and savings accrued from TRL-related activities.

This retailer also embedded the TRL concept across the business by both ensuring that everybody was account-able and that it fed into the core principles of the business: ‘We created goals for everybody on TRL – all functions across the business; you have to relate what you do to the overall objective of the business’ [RI17].

While others have adopted a much more limited approach to how they organize for TRL, often focused around the existing loss prevention function, all early adopters agreed that an analytical capability was key to ensure a modicum of success – capacity to pull the numbers together from across functions and IT platforms to then guide the work and measure the impact.

Advocate for TRL – Act as Agents of Change

Whilst a common organizational approach to TRL was not evident, where there was much more consistency was in strongly advocating an advisory role for those tasked with ‘delivering’ TRL in the business. The sheer breadth of the TRL concept has often been the greatest concern for those thinking about introducing it into their organizations – bringing a plethora of losses into one place, creating an overwhelming portfolio of responsibility that is likely to strike fear into even the most capable of retail executives. As one respondent put it:

My advice would be as soon as you create a TRL team then everybody is going to assume you will fix it, so we intentionally organized whereby the rest of the business remained responsible for this – don’t become a dumping ground for all problems [RI6].

The online survey collected some data that graphically illustrated the extent to which responsibilities for a range of losses were distributed across retail functions (Figure 14). Respondents were asked to indicate which function had overall responsibility for 11 areas of loss covered by the TRL typology.

While for some of the more traditional forms of loss, such as internal and external theft and cash losses, the loss prevention function was the dominant function, for other areas, there was a much more mixed economy with Store Operations, Finance and others being held accountable for different types of losses.

In many respects, this chart graphically illustrates the cross functional interplay that the TRL concept generates, making if extremely difficult to identify and hold accountable any one group for its overall implementation and control.

The answer for many adopters was to create a TRL function that acted as ‘agents of change’ – understood the issues but were not held responsible for delivering the change:

We act as agents of change – persuade others to make the changes. You have to hold up a mirror and say who is going to deal with this – well you are! You are the best to do it – you know the process and systems best [RI13].

This consultancy approach to TRL seemed to work well for a number of the loss prevention respondents interviewed for this research – have a form of strategic oversight and influence – ‘dotted line’ responsibility, particularly for those areas which are beyond the traditional spheres of influence.

Review Reporting Structures for TRL

While there is little sectoral consistency in loss prevention-related reporting structures, with some reporting in to Store Operations, others Finance or Risk Management/Services, a number of respondents reflected upon what they considered most appropriate when advocating a TRL-driven approach to thinking about the management of retail losses. Although not universal in anyway, a significant proportion of those interviewed felt that given the broad ranging nature of the TRL typology, often way beyond the confines of the retail store and a focus just upon the loss of merchandise, that Finance offered the most appropriate reporting hierarchy: ‘We report in to the CFO and that is key, because they understand the metrics and the ROI modelling [RI7]; ‘Reporting in to the CFO has made all the difference to delivering TRL; I cannot underscore how important this is [RI4]. Again, corporate norms, cultures and conventions are likely to influence decisions around reporting structures, but there does seem to be a high degree of logic in the Finance function, at the highest level, having some form of overall responsibility for the management of TRL, certainly given its breadth and focus upon the value of losses.

Prepare for Organizational Antagonism

Although the TRL concept was developed to enable retail organizations to understand more broadly the impact of loss and how it can be more effectively controlled and managed, its overarching cross functional reach also has the potential to generate political friction. As one respondent vividly described it: ‘While senior management are supportive of expanding this [TRL] out to include more categories, initially they were not very excited by the idea – mainly for sensitivity issues – you could be calling out other groups that don’t necessarily report into Loss Prevention [RI15].

This sense of resistance, or a concern that the loss prevention function could be viewed as ‘stepping on toes’ was a common theme amongst early adopters:

In the merchant world I wouldn’t say it was met with resistance but what slowed the adoption down in that realm was their naivetes about what their responsibility was to have ownership as well. So, we are still finding we have to go through a loss 101 with merchants to help them understand that they own part of how this model needs to operate to drive performance [RI17].

Others were more explicit about the negative reaction to what some regarded as the ‘expansionist ways’ of the loss prevention function: ‘We had hurt feelings – stages of opposition in the business – anger, denial, but then eventually acceptance and understanding [RI13].

For some respondents it was important to ensure they had good data when making the case with groups that might be at best ambivalent about ‘sharing’ responsibility for a TRL-related area of loss: ‘Do your homework, do not go in with bad information as you will not recover from that’ [RI9]; ‘I don’t want them doing it out of fear but because they can see the value; we needed to pull the data together to help them understand the opportunity’ [RI1].

In this respect, the loss prevention function needs to ensure that they are portrayed as a group focused upon adding value and not stripping out responsibility from other functions.

A useful tool that is commonly applied in change management projects that cut across organizational functions is Stakeholder Analysis (9), which focusses upon understanding the attitudes of groups likely to be impacted by or required to participate in a given project. Advanced work can then be done with particular groups to try and mitigate any concerns they might have prior to the start of the project. It may well be worthwhile, therefore, undertaking a TRL based Stakeholder Analysis prior to the introduction of this concept into a retail business.

Think About the ‘Right’ Name for your TRL

While the term ‘Total Retail Loss’ is now a relatively well known phrase amongst the global loss prevention community, becoming incorporated into some job descriptions and function titles (10), the main purpose of the underlying research was to foster a broadening in the understanding of what we mean by loss and not necessarily create a new title for the retail world to use. As such, Total Retail Loss as a name may well not properly describe the losses or approach adopted by any given retail company, indeed using the word ‘Total’ is undoubtedly a misnomer – there are many categories of potential retail loss not covered by the current typology. As such, a number of retail adopters of TRL have developed their own name to describe what this approach covers, including: Comprehensive Retail Loss; Total Profit Model; and Total Omni Loss being three examples.

For some others, the term ‘Profit Protection’ works well – recognizing a shift away from the more negative connotations characterized by words such as ‘Loss’ and ‘Security’, and a singular focus upon just one facet of loss such as ‘Asset’ Protection. The term ‘Profit Protection’ certainly encapsulates not only what TRL aims to cover, but also sends a clear message to the rest of the business that the associated activity is focused on a primary goal shared by the rest of the business – maintaining a profitable trading position.

Avoid Terminological Confusion

It is perhaps understandable, given that the term ‘shrinkage’ or ‘shrink’ has been part of the lexicography of retailing for more than 150 years, that its use remains very dominant. But as argued in the original research report, it is a term that lacks any common definition and typically measures only one aspect of retail loss – the discrepancy between expected and actual stock levels.