Contractual Terms for Reducing Food Waste

How contractual terms can impact on and improve food waste

Table of Contents:

- Abstract

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Approach and Methodology

- Findings - Causes of Waste

- - Cosmetic standards

- - Stock Piling

- Types of Forward Contracts

- - 1. (a) Whole Crop Purchases

- - 2. (b) Investment Contracts

- - 3. (c) Scan Based Trading Contracts

- Secondary Resale Contracts

- - 4. (a) Backward Selling Contracts

- - 5. (b) Forward Selling Contracts

- Key Take Aways and Further Research

Languages :

Reducing food waste to 50% by 2030 is a global priority. Retailers across the world are taking several initiatives such as improving store operations and demand forecasts to step up to this target. However, estimates suggest that over 32% of fresh food waste occurring before reaching consumers’ homes happens upstream in the supply chain at farms, manufacturing units and distribution centres. In this paper, we use a combination of stakeholder interviews and literature review to identify two key reasons for this wastage and outline ways in which retailer-led partnerships can help in profitably reducing it. We find that the primary reasons for waste are rejection of produce by retailers/suppliers at the farms due to its inability to meet cosmetic standards and piling of stock at various points in the supply chain to proactively meet customer demand. A key structural determinant of wastage due to these reasons is the design of contracts between players in the supply chain which fail to take a holistic approach in integrating the cost of food waste into the incentive structures of each player in the supply chain. For instance, cost of produce rejected at the farm due to cosmetic reasons is largely borne either by the farmer or by the end consumer but not by retailers or produce aggregators. To address this issue, we outline five innovative contractual types categorized into two broad sections that are either being used or being considered by retailers across that globe – forward and secondary resale contracts. Forward contracts include strategies to effectively purchase the produce to jointly maximize profits and minimize waste whereas secondary resale contracts include strategies for handling produce that is purchased but remains unsold. We particularly focus on retailer-led partnerships as they have the highest bargaining power in most fresh food supply chains. Besides enlisting contractual types, our study also provides a qualitative assessment of the efficacy of each contract type in reducing food waste. We find that forward contracts are more effective in comparison to secondary resale contracts. In particular, whole crop purchase contracts where retailers agree to purchase the entire crop produced by farmers irrespective of its quantity or cosmetic standards are most effective wherever applicable

Abstract

Reducing food waste to 50% by 2030 is a global priority. Retailers across the world are taking several initiatives such as improving store operations and demand forecasts to step up to this target. However, estimates suggest that over 32% of fresh food waste occurring before reaching consumers’ homes happens upstream in the supply chain at farms, manufacturing units and distribution centres. In this paper, we use a combination of stakeholder interviews and literature review to identify two key reasons for this wastage and outline ways in which retailer-led partnerships can help in profitably reducing it. We find that the primary reasons for waste are rejection of produce by retailers/suppliers at the farms due to its inability to meet cosmetic standards and piling of stock at various points in the supply chain to proactively meet customer demand. A key structural determinant of wastage due to these reasons is the design of contracts between players in the supply chain which fail to take a holistic approach in integrating the cost of food waste into the incentive structures of each player in the supply chain. For instance, cost of produce rejected at the farm due to cosmetic reasons is largely borne either by the farmer or by the end consumer but not by retailers or produce aggregators. To address this issue, we outline five innovative contractual types categorized into two broad sections that are either being used or being considered by retailers across that globe – forward and secondary resale contracts. Forward contracts include strategies to effectively purchase the produce to jointly maximize profits and minimize waste whereas secondary resale contracts include strategies for handling produce that is purchased but remains unsold. We particularly focus on retailer-led partnerships as they have the highest bargaining power in most fresh food supply chains. Besides enlisting contractual types, our study also provides a qualitative assessment of the efficacy of each contract type in reducing food waste. We find that forward contracts are more effective in comparison to secondary resale contracts. In particular, whole crop purchase contracts where retailers agree to purchase the entire crop produced by farmers irrespective of its quantity or cosmetic standards are most effective wherever applicable

Foreword

The ECR Retail Loss Group is the flagship for collaboration on retail loss and since 1999, we have delivered a constant stream of new thinking, tools and techniques that enable and have proven the value of collaboration.

However, there remains a huge opportunity for better collaboration on the problem of food waste in the supply chain. The ECR group and the CGF are thus very happy to present this new research and discussion paper on the role of commercial contracts and food waste prevention.

The report brings to the attention of the industry some important considerations on how different contract types will lead to different levels of motivation to tackle food waste.

We would encourage our members to consider the role that contractual terms can and should play in preventing food waste and how they can better support retailer’s food waste strategies.

We would also encourage all trading partners to do more to share their actual data on food waste, sales and forecasted demand. As our previous report, “what does it take to collaborate” identified, the sharing of food waste data between organisations was one of the major impediments to better collaboration, and thus it would seem to be a very good place to start and a way in which to inform any future discussions on forms of trading contracts.

Above all, we hope this report starts a discussion, stimulating new debate and thinking inside your organisation.

I would like to thank the academics and all those experts that agreed to support this work – your contribution to helping the broader retailer and producer community to better understand this important issue is very much appreciated.

John Fonteijn

Chair of the ECR Retail Loss Group

Introduction

A third of all food harvested in the farm never reaches the fork for human consumption. In the US alone, the economic value of food wasted is estimated to be ~$ 218bn every year, about 1.3% of the country’s GDP. Alarmingly, over 40% of wastage is estimated to occur at consumer facing businesses (retailers, distributors, restaurants, food service providers) and another 43% at individual homes (ReFed 2016; Wrap 2020).

The scale of this waste has been recognized as a major concern by governments and businesses around the globe. The United Nations has included reduction of per-capita food wastage by 50% as a key Global Sustainability Goal for 2030 (FAO 2020). Countries such as the US and the UK have also set similar targets for their own countries (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs 2019; United States Environmental Protection Agency 2020). Businesses too have responded by piloting and adopting various solutions targeted at reducing food wastage. Solutions such as waste tracking analytics, packing adjustments, donation, storage and handling and so on are gaining popularity among the retailers (Eurocommerce 2017). For instance, from 2016, Sainsbury’s, the second largest chain of supermarkets in the UK, has converted its food waste into green gas which accounts for ~10% of its annual gas needs (Sainsburys 2017). Similarly, Walmart is currently piloting smart labelling technology to consistently monitor spoilage of food products in transit to their stores (Prudy 2016).

While these solutions are undoubtedly a progressive step towards reducing food waste, they are largely driven by the retailers and are confined within the boundaries of the firm. However, estimates suggest that only ~ 23% of the food wasted before reaching a consumer’s home happens in retail stores. Other consumer facing businesses such as the restaurants and institutional food providers contribute to an additional 46% whereas the remaining 31% occurs at farms, suppliers and manufacturing units1 (ReFed 2016). In this study we consider the role of supply chain partnerships and revisions to commercial terms in extending retailers’ efforts to reduce waste across the supply chain. We particularly focus on partnerships led by retailers as they have the highest bargaining power in the fresh food supply chain. Also, we extensively focus on preventive measures as they are estimated to have a potential to save over 75% of the annual economic value of food waste, in contrast to 23% and 2% from food recovery and recycling measures respectively2 (ReFed 2016).

Approach and Methodology

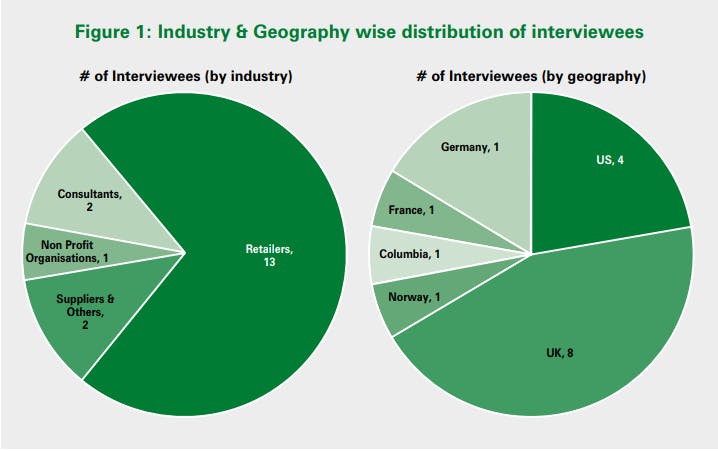

Interviews were conducted with eighteen executives specializing in commercial procurement and related fields in fresh grocery supply chain across various geographies and industries. Figure 1 shows the distribution of interviewees by industry and geography. These interviews were supplemented with over 100 hours of desk research involving review of literature from various academic journals and policy think tanks.

Findings - Causes of Waste

Our analysis identified two major reasons for wastage of food before it reaches the retail store –

(i) cosmetic standards and

(ii) stock piling.

Cosmetic standards

One of the major reasons for perfectly edible produce getting wasted at the farm is produce not meeting cosmetic standards demanded by the retailers. Farm waste report by Feedback estimates that in the UK alone, over 37,000 tons of food, about 16% of the total food grown is rejected by retailers due to their cosmetic inferiority (Bowman 2018). Often, farmers complain of not having clearly defined cosmetic standards that are contractually enforceable and attribute retailers’ rejection based on cosmetic standards to their revised forecasts. When faced with such vagaries, farmers, due to lack of other sale outlets, typically turn the harvest either into food waste or use it to replenish organic matter in the soil.

Stock Piling

Another reason for perfectly edible produce going to waste is stock piling or accumulation of inventory. Stock piling can happen either at the beginning of the supply chain, that is at the farm or far into the supply chain at distribution centres of suppliers and retailers. Primary reason for stock piling at the farm is a crop flush. When seasonal fruits and vegetables such as cauliflower, strawberries and avocados are overproduced, there is an excess supply of them within a short period of time without commensurate demand. This supply-demand mismatch is often observed to lead to waste. While there are multiple strategies such as cold storage, price drops and produce promotions that could be adopted to consume/preserve the excess produce, it is often observed that retailers and suppliers continue to place purchase orders solely based on their demand forecasts and leave the excess produce at the farm. Given that farmers in most countries are disaggregated, they neither have the scale to invest in capital intensive technologies such as cold storage nor have the market power to influence the price to push further demand. Thus, they aren’t left with many options beyond turning the harvest into waste.

Next, once the produce is lifted from the farm, it spends a large proportion of its shelf life flowing through the supply chain. Retail store managers, in order to be able to meet the consumers’ demands proactively demand high responsiveness from their suppliers/distribution centres. Consequently, suppliers/distribution centres tend to accumulate perishable inventory at several points in the supply chain in anticipation of demand from retail stores leading to wastage. Occasionally, we also came across instances of suppliers sending such accumulated inventory that is close to its expiry free of cost to the retailers allowing them to decide if they want to sell it at a subsidized price or trash it as waste. Further, we find that in several cases, particularly for slow moving products, the market incentive structures are also more conducive towards stock piling. That is, the cost of storing and trashing an SKU (if not sold) is significantly lower than the expected profit margin from the SKU (if it were sold). This too encourages several retailers and suppliers alike to stock more and thereby waste more. Beyond cosmetic standards and stock piling, other major reasons for food waste include inaccurate demand forecasting and unconducive packaging.

A major structural determinant of these reasons is the design of prevailing contracts between retailers and suppliers which take the form of a fixed price for a fixed quantity of produce over a fixed period of time. With each player maximizing his/her own profit, such fixated nature of contract design fails to account for costs associated with food waste at each step in the supply chain. Given the heterogeneity in market power among the players in the supply chain, typically, it is either the consumers or the producers who inadvertently pay for food waste. For instance, in a season where a large proportion of produce does not match cosmetic standards due to unforeseen climactic conditions, supply of the commodity in the market reduces as retailers leave the ‘not-so-goodlooking’ produce at the farm. Not only does this lead to an increase in price for the final consumer due to supply-demand mismatch but also leads to an increase in wastage of produce at the farm as most farmers do not have other sale outlets to consider. This stark simultaneity of producers wasting the crop and consumers overpaying of the same crop a major drawback for such fixated contract designs.

In this study we identify innovative contract types where this fixated nature of traditional contract design can be relaxed. To this effect, we find five innovative types of contractual agreements categorized into two broad buckets either being implemented or being considered by retailers across the globe – Forward contracts and Secondary Resale Contracts. The current level of commitment from the leadership and sophistication in implementation is highly varied across the retailers. While some retailers such as Tesco (Tesco 2019a) have adopted contractual agreements to reduce waste as a strategic priority, many are yet to embark on this journey. A large proportion of retailers we interviewed belonged to latter category.

Below, we describe these agreements, their variants and contexts in which we expect them to be effective.

Types of Forward Contracts

Forward contracts include strategies to effectively purchase/manage the produce to jointly maximize profits and minimize waste. We observed three kinds of such contracts that are usually used in different contexts – Whole Crop Purchases, Investment Contracts and Scan Based Trading Contracts.

1. (a) Whole Crop Purchases

A dominant strategy to address the issue of cosmetics standards and stock piling is the “Whole Crop Purchase” contracts. In this strategy, retailers engage with the farmer directly and commit to purchasing everything produced by them (including the produce that does not meet cosmetic standards). In return to the surety, farmers agree to sell their produce to the retailer at a reduced price. In some cases, this strategy takes the shape of a wage contract where the retailers agree to pay the farmer a fixed wage for the crop. This strategy serves three purposes – decreases cost of goods for retailers, increase a farmer’s income and reduce waste. Waste reduction in this form of contracting is primarily driven by clear visibility of inventory from the time harvest which enable the retailers to plan the downstream supply chain accordingly.

A key component in success of this strategy is the retailer’s ability to utilize the produce that does not meet the cosmetic standards effectively under the expiry time constraints. A prominent retailer that seems to have successfully navigated this issue is Tesco, the third largest retailer in the world. It has adopted this strategy since 2013 and engages in long-term contracts of 3 – 5 years with over 2,500 farmers of all sizes across the UK. Produce that meets the cosmetic standards is usually sold on the shelves and the rest is either used in the in-store live kitchen or converted into packets of frozen chopped vegetables to be sold as a home brand. Some of the leftover produce is also pushed to downstream players such as restaurants and food service institutions (Tesco 2019b). Other prominent retailers to have adopted this strategy are Mercadona, Metro Cash & Carry and Jeronimo Martins (Eurocommerce 2017).

Though this strategy has proven successful for Tesco and is likely to be effective for vertically integrated retailers at large, it is important to note that it comes with logistical complications of dealing with multiple suppliers (farmers) and therefore may not be applicable for all retailers. For ease of doing business, it is natural for retailers to depend on an aggregator (supplier) who can ensure their daily demands are seamlessly met and there is a high possibility that such dependence is more cost effective than engaging with multiple farmers. Also, not all retailers may have in-store kitchens and a good network of downstream players to effectively utilize the entire produce. In such scenarios, retailers, can use their high bargaining power to enter into conditional contracts with their suppliers. That is, retailers could demand the suppliers to engage in Whole Crop Purchase Contracts to be able get their business. Few suppliers in the UK such as Branstons3 are already actively engaged in such contracts and a push by the retailers could incentivize several more to join the bandwagon.

Similar to Whole Crop Purchases, Whole Animal Purchase Contracts between farmers and retailers/suppliers are possible and exist in practice. However, the issue of food waste among animal products is not as worrisome as it is in the case of fresh produce. Supply chains for animal products are largely demand driven unlike fresh produce which are supply driven. That is, an animal is butchered only when there is a consumer demand at the store. Such flexibility is not possible in case of fresh produce, particularly among those commodities which are seasonal, and require robust long-term demand forecasts. Also, animal products such as sausages typically have a larger shelf life than fresh produce and can afford to spend longer durations of time flowing through the supply chain. Lastly, it is very common for slaughterhouses to have multiple contractual agreements with different players in the downstream for different animal parts thereby reducing the wastage burden on retailers alone.

2. (b) Investment Contracts

Another form of purchase contract occasionally used involves capital investments. In these contracts, both retailers and the suppliers jointly identify opportunities to reduce waste and agree upon making necessary investments in technology for sustained collaboration. Incentives for such collaboration are created in the form of long-term quantity or price contracts. Typically, these contracts are typically effective in contexts where significant modifications in suppliers’ operations are needed to meet the retailers’ waste reduction objectives. An emerging area where such contracts are being considered is packaging. Several large retailers are working with suppliers and packaging producers to enhance the shelf life of their self-branded products (Skyes 2019).

3. (c) Scan Based Trading Contracts

This strategy is particularly effective in contexts where the primary driver of food waste is stock piling in the supply chain. It involves retailers acting solely as shelf-space providers allowing the suppliers to manage inventory from end-to-end. Suppliers foot the costs of distribution in exchange for their ability to manage their own portfolio of SKUs pre-authorized by the retailer while maintaining product quality. At the same time, retailers receive a commission from the supplier for every unit sold without incurring handling and inventory holding costs in exchange to the shelf space.

In contrast to traditional procurement practices of the retailers which involve aggregation of demand across several stores, this strategy out-sources the responsibility of aggregation to the suppliers. Such outsourcing can be effective when dealing with highly perishable commodities associated with high order frequencies and low order quantities at the store level. Typical examples of such commodities are bread and bakery products. Such products, when procured using traditional practices are likely to spend a significant part of their shelf life either flowing through the supply chain or sitting in a distribution center leading to increase in wastage. However, in contexts where suppliers have logistical capabilities to quickly respond to customer demand and network capabilities to aggregate demand from stores operated by several retailers, the aforementioned nature of wastage can be avoided, albeit with a slight increase in cost of logistics. Evaluation of relative tradeoffs between potential increase in logistical costs and decrease in waste can be a good starting point for consideration of these contracts.

Historically, one of the major impediments in implementing such contractual agreements has been information asymmetry, where the supplier does not have visibility over sales happening at the retail store. Another major impediment is shrink, and the question of who pays for the products that are lost, either stolen, damaged or out of date (Choi 2016). However, with store replenishment and customer check-out processes largely digitized across retail outlets, real-time data on units sold and units on the shelves can now be seamlessly shared with all parties involved. This has motivated several retailers to consider engaging in such contracts to a varying degree. Currently, such contracts are a standard practice among milk and dairy products at several retail outlets and have the potential to be extended to other SKUs with similar demand and shelf life characteristics, particularly in contexts where direct store delivery is a common practice.

A major flipside to this strategy is that the retailers, who are closer to the inventory located in the store shelves, have no incentive to work towards reducing waste. In fact, one can imagine scenarios where retailers could use their bargaining power to push the suppliers to stock more to ensure overall customer satisfaction in their store. In such scenarios, retailers might be leading to more wastage without paying the price for it.

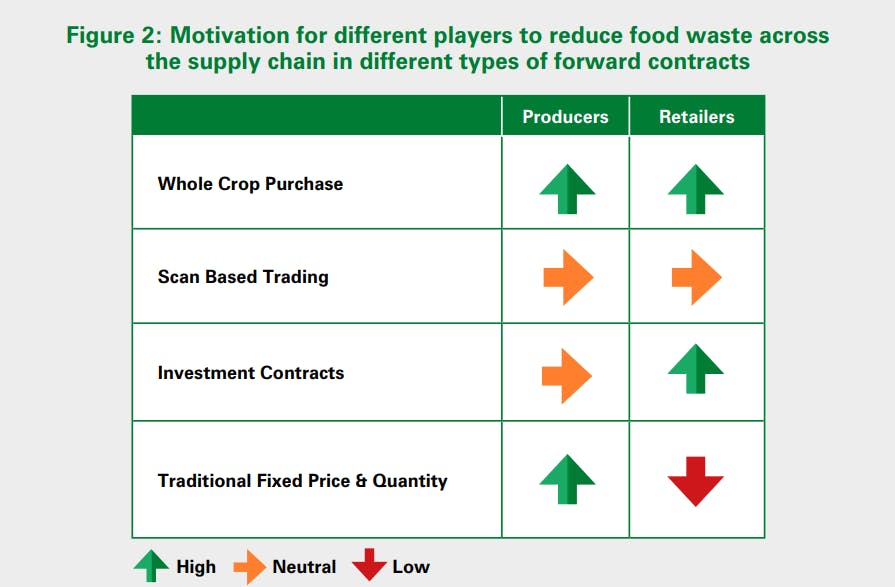

Figure 2 summarizes the motivation for producers/suppliers and retailers towards reducing food waste across different forward contract types across fresh food supply chain. Our notion of producers includes players such as farmers and manufacturers whereas retailers includes all customer facing grocery shopping outlets. In whole crop purchases, both producers and retailers are equally motivated to reduce food waste as the costs of waste are shared by both parties. For example, Branston’s (potatoes) re-purposed and processed the potatoes that did not meet the required standards into other products, such as ready-made meals. Whereas in investment contracts, the cost of investment is largely borne by the retailers and therefore they have a higher motivation towards food waste in comparison to producers. In the meat category, an investment in new “skin tight” packaging lead to a 50% reduction in the food waste supplied from a major meat producer (Hilton Foods) Tesco 2019b However, in Scan Based Trading contracts, both retailers and producers play a counterbalancing role against each other with regards to food waste. While producers may want to stock more to sell more thereby wasting more, retailers may push back excess stocking by imposing shelf space constraints (vice-versa where retailer being keen on stocking more and producer pushing back with supply constraints may also happen). Lastly, in traditional fixed price contracts, retailers have little motivation to address food waste as the cost of waste is not often included in the contractual terms.

Secondary Resale Contracts

These strategies entail retailers selling the unsold food products to identified partners at a discounted price. While these contract types are largely focused on addressing the symptom and not the cause of food waste, they are still important as demand forecasts, despite their increasing sophistication, could include significant errors. Unlike donations, secondary resale as a strategy is designed to be for profit and is observed in two forms – backward selling and forward selling.

4. (a) Backward Selling Contracts

This strategy includes reverse logistics where the retailer sends back unsold products procured from a supplier within a stipulated time period. Unlike Scan Based Trading strategies which are applicable with products with short shelf life, small order quantities and high order frequency, backward selling option is more relevant for products with reasonably long shelf life, large order quantities and low order frequency. In most cases, the supplier bears the cost of logistics and in return gets the opportunity to procure raw materials for reuse/re-manufacture at a significantly lower cost. Evidently, the success of this strategy is largely dependent either upon the suppliers’ ability to re-use the products or upon their downstream network of discount stores, restaurants and food institutions that are open to purchase such re-used/remanufactured products. While this strategy is rather uncommon among large retailers which themselves have a strong downstream network, it is occasionally considered by small and medium sized retailers, specialty and convenience stores.

5. (b) Forward Selling Contracts

Forward selling includes offering goods that are unsold to downstream players at a subsidized price. A notable example to this strategy is the Carrefour group which converts unsold food products in each store into mini meals and sells it to consumers in the neighbourhood through a new technology platform called Too Good To Go (Carrefour 2018). However, this strategy is not very popular among large retailers as they tend to slash prices and push the products to consumers’ purchase basket. It is more often employed by discount retailers such as Grocery Outlet and Daily Table.

Key Take Aways and Further Research

In times when retailers are largely focused on food waste initiatives confined to the boundaries of their firm, this research highlights the potential and possibilities of developing retailer-led contractual agreements that could significantly reduce food waste across the supply chain. Contractual agreements currently used by the retailers largely take the form of a fixed price for a given quantity over a mutually agreed time period. Often the price, quantity, time period and in some cases quality too, are decided based the retailers’ assessment of their store-level demands.

Our research finds that not only is such form of contracting restrictive from a food waste prevention standpoint but also limits the overall profit potential of the entire supply chain. We highlight innovative contractual types where price, quantity and time are decided using a holistic approach which includes store-level demand forecasts along with incentives/ disincentives of other players in the supply chain. For instance, in the case of Whole Crop Purchases, by considering the farmers’ concerns over rejection of produce, retailers can obtain their commodities at a reduced price in return to relaxation of their fixed quantity clause. The implicit idea in such contracts is that there is a joint responsibility assumed by both farmers and retailers to reduce waste and costs associated with it in a mutually profitable manner. In the case of Scan Based Trading, retailers agree to relax the fixed quantity clause in order to transition the responsibility of managing inventory to those in the supply chain who are most capable of reducing food waste. In doing so, they facilitate the overall reduction of waste in the supply chain thereby enabling the possibility of benefits from reduction being shared among all players in the supply chain.

Our research also takes a leap forward in qualitatively assessing the potential each type of contract holds in reducing waste. We find that by engaging in whole crop purchases or in conditional contracts with suppliers, retailers can play a significant role in decreasing waste at the farm which constitutes ~16% of the total food waste (ReFed 2016). Beyond being highly impactful in reducing food waste, we also find that these contracts are more feasible to operationalize in comparison to others. This is primarily because, store presence of most large retailers is geographically widespread providing them ample opportunities to utilize the whole crop. Also, among all the players in the fresh food supply chain, in most cases retailers have the highest working capital to be able to drive investments in necessary infrastructures such as cold storage warehouses and information sharing platforms, which are essential for the success of whole crop purchases. While retailers need not engage in such investments all by themselves, they can use their bargaining power to create conglomerations of all players in the supply chain that stand to benefit from such an investment. Lastly, the ease of implementing this contract type comes from the fact that the networks of farmers and suppliers needed to operationalize it already exist in the current supply chain. All that is needed is a nudge from the retailers to modify the contractual terms under which these networks currently operate.

In order to ensure the intended results are obtained, the design of any of these contracts needs a careful consideration of the context and the capabilities of the players involved. For instance, as discussed above, Scan Based Trading strategies, if not designed appropriately might incentivize retailers and willing suppliers to encourage more wastage in certain contexts. While the models followed by retailers such as Tesco and Mercadona offer a good headway into designing such contracts, in most cases it is not possible to replicate the same structure across several retailers. Therefore, retailers should consider running small pilot studies on the aforementioned contract types and document their pros, cons and implementational challenges. More generally, a clear framework that elucidates an exhaustive list of the pre-requisites that are needed, computes optimum price points and provides specific operational guidelines for each supply chain of fresh produce based on strengths and weaknesses of retailers (and their suppliers) is needed.

Further, it is important to study the pre-requisites needed for design of conditional contracts as there aren’t many precedents of this kind and evidently these require more logistical streamlining to operationalize. A major component of such operationalization would be investment in information sharing platforms where retailers can monitor suppliers’ actions, their costs, prices and quality of commodities. In fact, Tesco is already working with its suppliers to put such data sharing infrastructure in place (Askew 2018). The retailer is also urging other supermarkets to publish their data in a manner conducive to track and tackle waste (Grant 2019).

In the long run, more studies focused on suppliers and producers are needed to understand the circumstances in which suppliers will willingly engage in Whole Crop Purchases without the retailers having to use their bargaining power. If we could achieve that, we would have created a self-sustaining supply chain where incentives to reduce food waste across the supply chain are aligned with each individual player’s sustainability goals.

References

- Askew, K. (2018, September). What gets measured gets managed: Tesco’s suppliers commit to sharing food waste data. Retrieved on May 5, 2020 from https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2018/09/25/ What-gets-measured-gets-managed-Tesco-suppliers-commit-to-sharing-food-waste-data

- Bowman, M. (2018, February). Farmers talk food waste. Retrieved on May 5, 2020 from https:// feedbackglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Farm_waste_report_.pdf

- Carrefour (2018). Tackling Food Waste: Carrefour Joins Forces with Too Good To Go. Retrieved on May 4, 2020 from https://www.carrefour.com/en/newsroom/tackling-food-waste-carrefour-joins-forces-toogood-go

- Choi Min (2016). Moral Hazard, Power, and Risk Sharing in Scan-Based Trading. Retrieved on May 4, 2020 from https://repository.asu.edu/attachments/175020/content/Choi_asu_0010E_16291.pdf.

- Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (May 2019). Slashing food waste: Major players urged to ‘Step up to the Plate’. Retrieved on May 4, 2020 from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ slashing-food-waste-major-players-urged-to-step-up-to-the-plate

- Eurocommerce (2017). Rising to the food waste challenge. Retrieved on May 4, 2020 from https:// www.eurocommerce.eu/media/134575/Food%20Waste%20Brochure%20-%20final.pdf

- FAO (2020). Sustainable Development Goals, Global Food Loss and Waste. Retrieved on May 5th 2020 from http://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/indicators/1231/en/.

- Grant, K. (2019, September). Order supermarkets to publish food waste data, Tesco boss urges Government. Retrieved on May 5, 2020 from https://inews.co.uk/news/consumer/order-supermarketsto-publish-food-waste-data-tesco-dave-lewis-urges-government-636885

- Prudy, Chase (2016, July). Walmart has a smart new ploy to reduce rampant food waste. Retrieved on May 4, 2020 from https://qz.com/739772/walmart-has-a-smart-new-ploy-to-reduce-rampant-food-wasteselling-ugly-produce/

- ReFed. (2016). A road map to reduce food waste in US by 20 percent. (2016). Retrieved from https:// www.refed.com/downloads/ReFED_Report_2016.pdf https://www.refed.com/downloads/ReFED_ Report_2016.pdf

- Sainsburys (2017). Helping customers to cut food waste. Retrieved on May 4, 2020 from https://www. about.sainsburys.co.uk/making-a-difference/our-values/our-stories/2017/helping-customers-to-cut-foodwaste

- Skyes. T. (2019). The Shelf-Life Challenge. Retrieved on May 4, 2020 from https://packagingeurope.com/ the-shelf-life-challenge-iffa/

- Teso (2019) a. UK Food Waste Data 2018/19. Retrieved on May 4, 2020 from https://www.tescoplc.com/ sustainability/food-waste/topics/uk-data/

- Tesco (2019) b. Working with Suppliers. Retrieved on May 4, 2020 from https://www.tescoplc.com/ sustainability/food-waste/topics/suppliers/

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (2020). United States 2030 Food Loss and Waste Reduction Goal. Retrieved March 30, 2020, from https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/ united-states-2030-food-loss-and-waste-reduction-goal

- Wrap (2020, January). Food Surplus and Waste in the UK – Key Facts. Retrieved on May 5th 2020 from https://wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Food_%20surplus_and_waste_in_the_UK_key_facts_Jan_2020.pdf

(Endnotes)

- Authors calculations based on data reported on ReFed 2016

- Authors calculations based on data reported on ReFed 2016

- Based on ECR Shrink group’s interactions with Branstons group

Main office

ECR Community a.s.b.l

Upcoming Meetings

Join Our Mailing List

Subscribe© 2023 ECR Retails Loss. All Rights Reserved|Privacy Policy